Uranus may have more in common with Earth than we thought, 40-year-old Voyager 2 probe data shows

Revisiting old data from Voyager 2, scientists have worked out how a dense, shocked region of the solar wind could have manipulated Uranus' magnetosphere.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

The Voyager 2 mission may have caught Uranus at a special time during which the ice giant's radiation belts were being supercharged with electrons accelerated by a similar process to what can drive geomagnetic storms on Earth.

This realization, resulting from placing old data from Voyager 2 under new scrutiny, could help explain several puzzling aspects of Uranus's magnetic envelope.

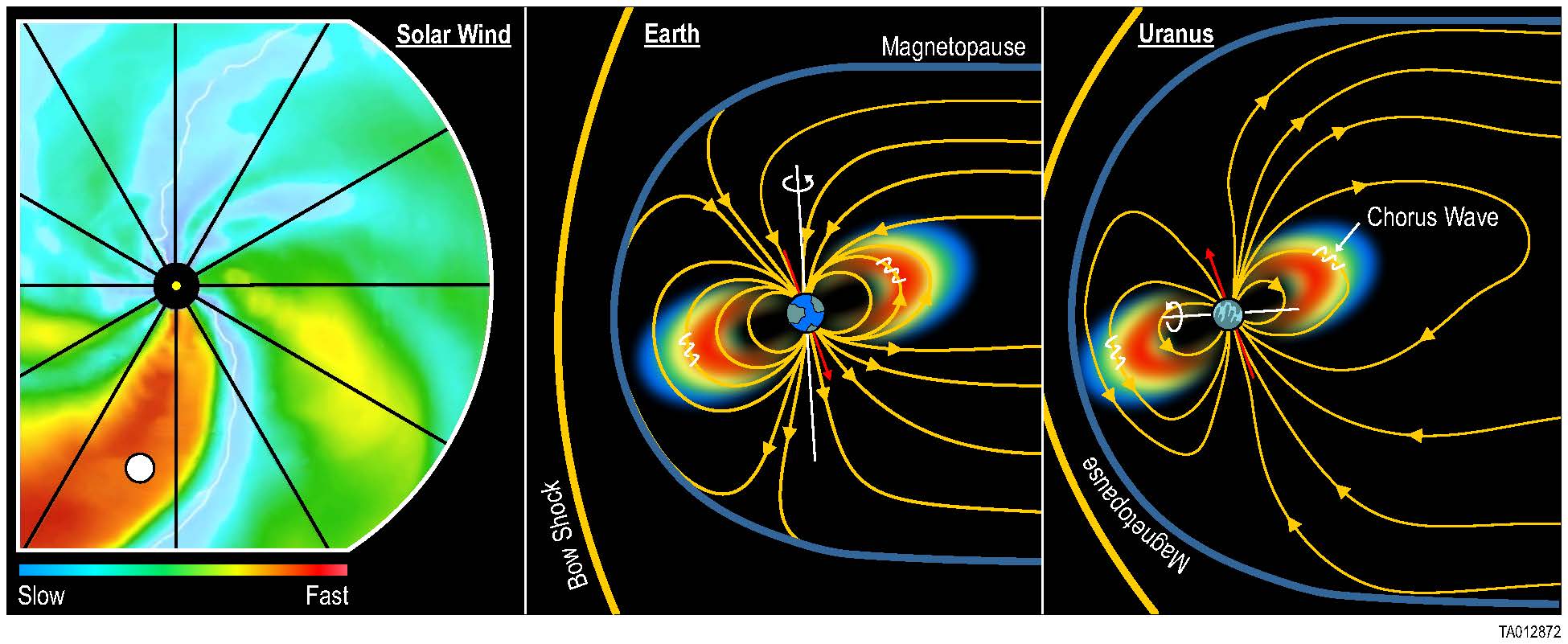

When the fast component of the solar wind, which emanates through coronal holes on the sun and is somewhat irregular, slams into slower portions of the solar wind, it results in electromagnetic shocks in the sleet of charged particles carried on the wind. Such an event is referred to as a co-rotating interaction region, and when one occurs near Earth, it can be one of the causes of geomagnetic storms that can result in the aurora.

The solar wind extends out past Earth, and even beyond Uranus, Neptune and the Kuiper Belt to form the 'heliosphere', which is a magnetic bubble around the solar system. The realization that a co-rotating interaction region may have been passing Uranus at the same time as the Voyager 2 encounter on Jan. 24, 1986 could be the missing piece of the puzzle that has eluded scientists for nearly four decades.

Voyager 2 remains the only mission to have visited Uranus (and Neptune, for that matter). What it found was a cold, icy gas bag with a very strange magnetosphere, which is what we call the magnetic envelope generated by the planet's intrinsic magnetic field. The north–south orientation of that magnetic field is tilted by 59 degrees relative to Uranus' axis of rotation, which itself is tilted by 98 degrees relative to the ecliptic plane. Furthermore, the magnetosphere is off-center inside Uranus, allowing for a much stronger magnetic field in the north than in the south.

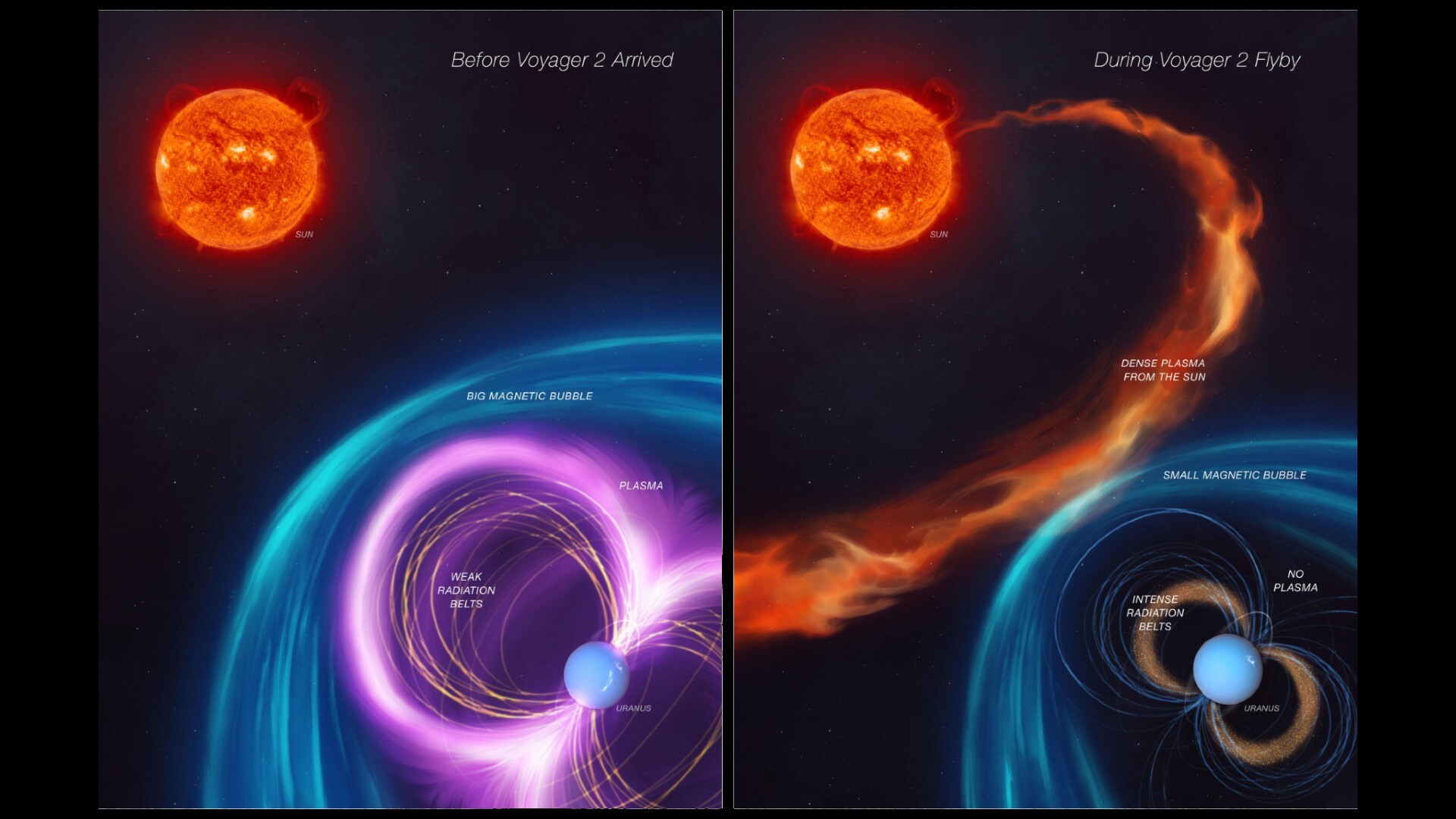

Just as Earth's magnetosphere is ringed by belts of radiation in the form of charged particles, so is Uranus. Yet, when Voyager 2 arrived in 1986, it found that there was barely any plasma (ionized gas) contained within Uranus' magnetosphere. In fact, the magnetosphere had been compressed and the plasma seemingly squeezed out. What was in abundance were electrons, contained in surprisingly densely populated belts.

Back in 1986, scientists thought that a solar-wind event like a co-rotating interaction region would scatter electrons present in Uranus' magnetosphere into the planet's atmosphere. However, almost four decades of studying the solar wind and how it interacts with planets has taught us something different.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Science has come a long way since the Voyager 2 fly-by," said the Southwest Research Institute's Robert Allen, who led the new research, in a statement. "We decided to take a comparative approach looking at the Voyager 2 data and compare it to Earth observations we've made in the decades since."

While on some occasions co-rotating interaction regions can scatter electrons into a planet's atmosphere, studies of their interaction with Earth have shown that such an event can also dump a lot of energy into the magnetosphere.

"In 2019, Earth experienced one of these events, which caused an immense amount of radiation-belt electron acceleration," said Sarah Vines, who is also from the Southwest Research Institute. "If a similar mechanism interacted with the Uranian system, it would explain why Voyager 2 saw all this unexpected additional energy."

In the absence of a second mission to Uranus after Voyager 2, scientists have learned to squeeze all they can out of the old Voyager 2 data instead, using new insights and techniques garnered over the past four decades, to learn more about the ice giant. These new findings come just a year after another team looked at the old data to conclude that the solar wind had indeed compressed Uranus' magnetosphere, squeezing out the plasma normally present.

For those four decades, scientists had thought that Uranus' magnetosphere was always in this bizarre state, but now we are learning that we simply caught it at a rare moment, and that what Voyager 2 measured might not be the status quo.

"This is just one more reason to send a mission targeting Uranus," said Allen.

Uranus is not alone in having a strange magnetosphere. When Voyager 2 encountered Neptune three-and-a-half years later, it found that it too had a displaced and tilted magnetosphere, just like Uranus. Indeed, the findings of the new analysis of the old Uranus data "have some important implications for similar systems, such as Neptune's," added Allen.

Perhaps misaligned magnetospheres are typical of all ice giants, both in the solar system or beyond. Or perhaps they are atypical, or symptoms of Uranus and Neptune's unique histories. Either way, new missions are urgently needed to provide the first close-up data in nearly 40 years and counting. Fortunately, a new Uranus mission is currently a top priority for NASA.

The new analysis of the old Voyager 2 data can be found in a paper published on Nov. 21 in Geophysical Research Letters.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.