'Crash Clock' reveals how soon satellite collisions would occur after a severe solar storm — and it's pretty scary

"2.8 days is the average expectation value for time to the first collision."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

How long would it take for satellites to begin to collide with space junk and each other if they were to suddenly lose their ability to avoid each other?

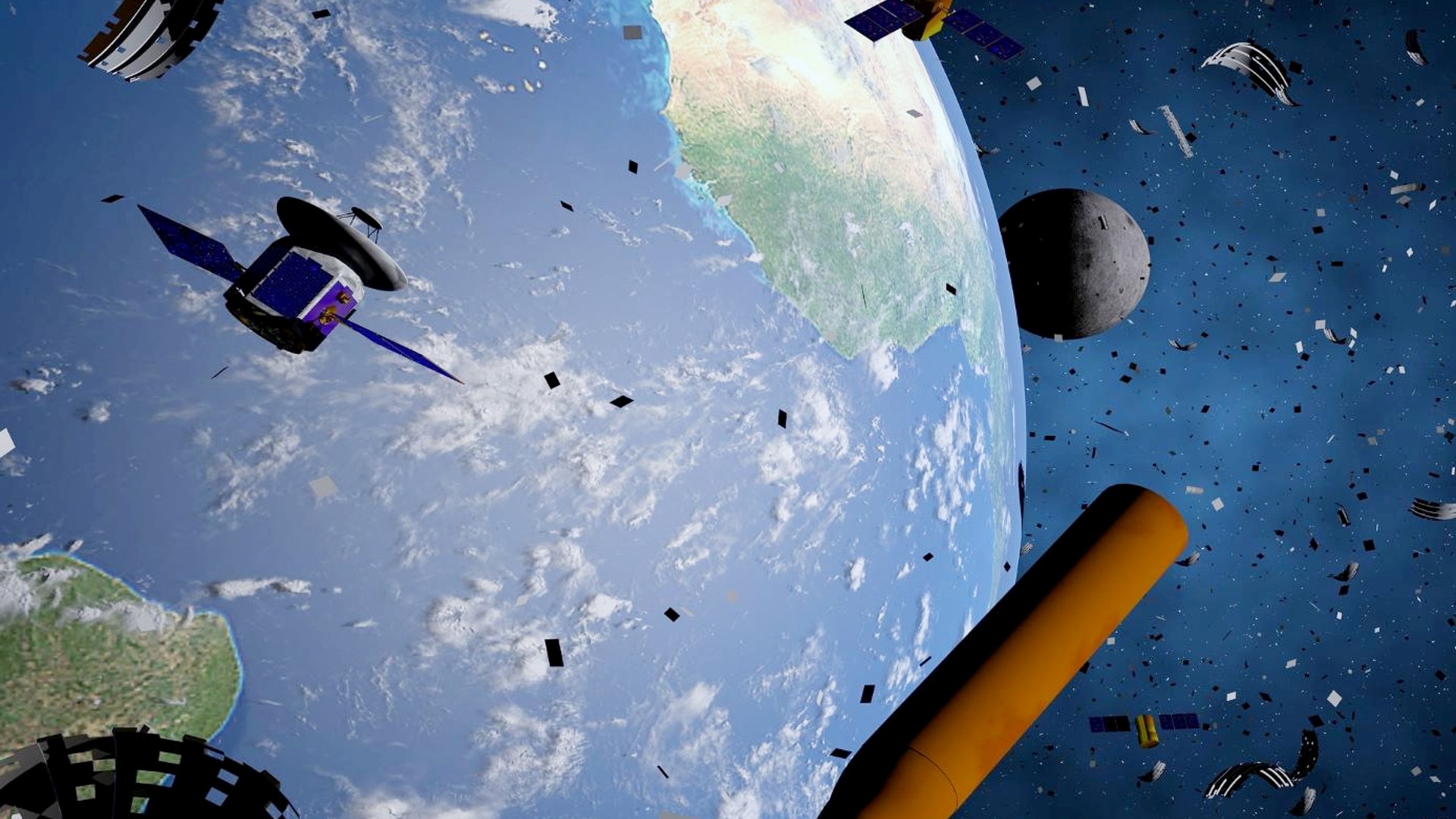

A new study finds that, with the immense quantity of satellites that hurtle in Earth's orbit today, the first smashup would occur in less than three days, potentially triggering a dangerous collision cascade that could quickly make space around the planet unusable.

The study, published on the online preprint repository arXiv, has not yet been peer-reviewed, the authors caution, but it raises questions about the sustainability of humanity's use of space. The researchers call this expected time-to-collision value the Crash Clock and calculated it by running a model of all known objects in space and determining an average collision rate for various orbital regions in the absence of avoidance maneuvers.

They found that regions in low Earth orbit (LEO) at altitudes around 300 miles (500 kilometers), where most satellites of megaconstellations like SpaceX's Starlink reside, could see a collision in as little as 2.8 days. For comparison, the team ran an identical simulation with numbers of satellites and space debris in orbit from 2018. At that time, it would have taken 128 days for the first collision to occur, Samantha Lawler, an associate professor in astronomy at the University of Regina in Canada and one of the paper's authors, told Space.com.

"It's been a big change since 2018," Lawler said.

The idea that satellites in orbit could suddenly lose their ability to avoid collisions is not science fiction. Every time the sun unleashes a coronal mass ejection (CME) — a burst of magnetized plasma — toward Earth, the planet's tenuous upper atmosphere thickens. Satellites in LEO then experience more drag and slow down, meaning their trajectories become impossible to predict.

In 2003, for example, after the Halloween storm — one of the most intense space weather events of the last three decades — satellite operators lost track of positions of their spacecraft for days. At that time, a few hundred operational satellites orbited the planet, and no collision occurred. And the Halloween storm was only a fraction of what the sun is capable of. A stronger solar storm, perhaps as potent as the Carrington Event of 1859 — the most intense recorded solar storm in human history — would take a week or more to fully subside.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"At the beginning of a solar storm, there's a huge increase in atmospheric density and things start to get pulled down," Sarah Thiele, an astrophysics researcher at Princeton University, and corresponding author of the paper, told Space.com. "Before things start getting back to normal, you have uncertainties of several kilometers in the positions of satellites, and it becomes impossible to estimate where objects are going to be in the future — and therefore it becomes impossible to predict collisions and conduct avoidance maneuvers."

The Crash Clock data suggests that, in 2018, near-Earth space would most likely have had enough time to recover from the most extreme solar storm before the first collision occurred. In 2025, however, an orbital smashup would be almost certain. Such a collision would create thousands of fragments that would threaten everything in their path, potentially triggering an unstoppable chain of events. With every subsequent crash, the affected orbital region would become more unsafe — a nightmare scenario known as the Kessler syndrome.

"2.8 days is the average expectation value for time to the first collision," Thiele said. "It's a probabilistic estimate. We're not saying that for sure this is going to happen in exactly that time. It's what you might expect."

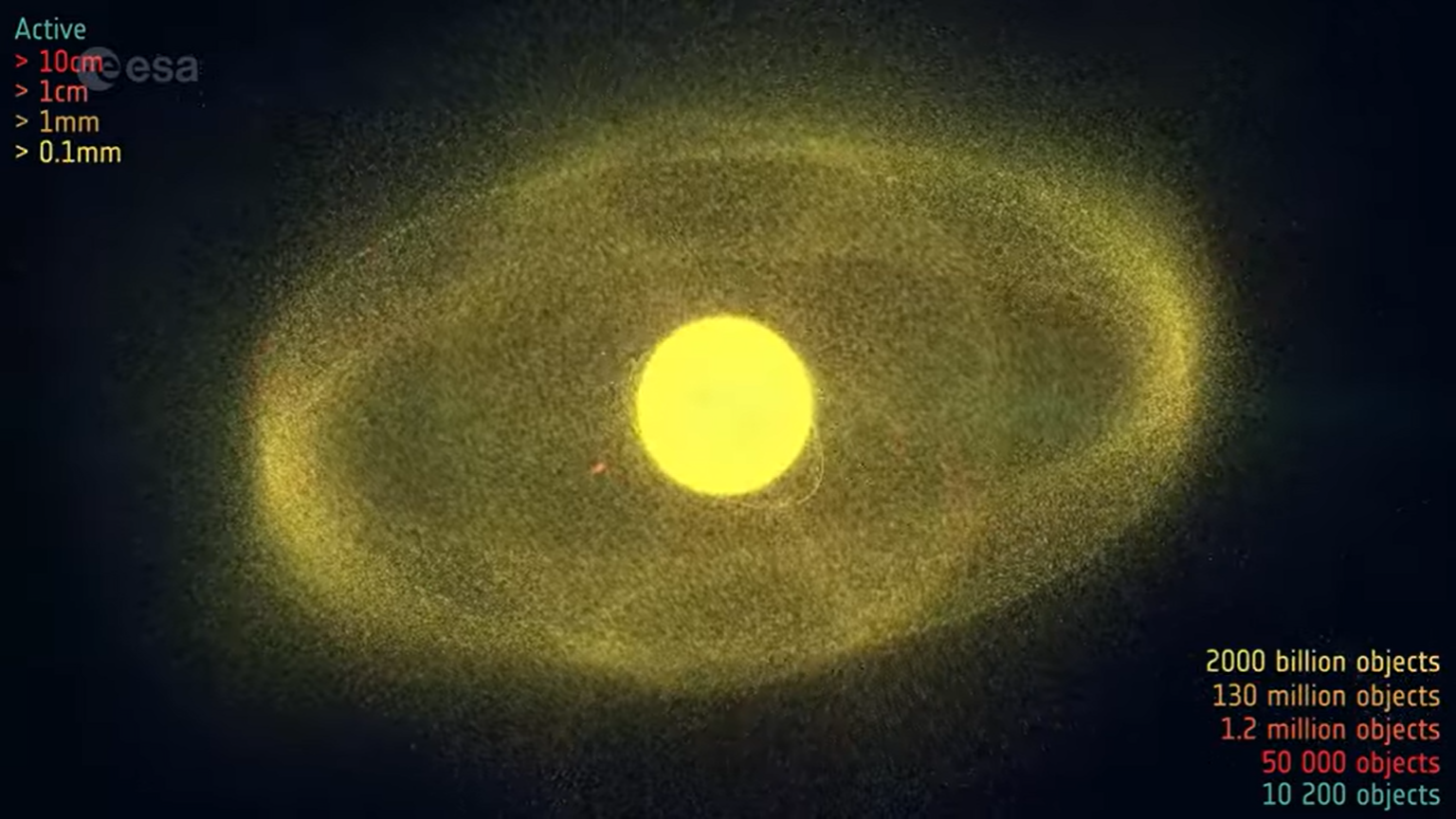

Currently, some 13,000 functioning satellites orbit the planet, according to the European Space Agency, together with more than 43,500 pieces of space debris — defunct satellites, rocket stages and collision fragments — that are large enough to be tracked. These objects circle the planet at speeds of about 7.8 kilometers (4.8 miles) per second, and their paths frequently intersect. Space situational awareness companies, the U.S. Space Command and other agencies predict satellite trajectories and alert operators to perform collision-avoidance maneuvers in case of close approaches. Starlink, by far the currently largest constellation in orbit, encompassing around 9,000 functioning satellites, performed 145,000 collision-avoidance maneuvers in the six months prior to July 2025, equivalent to around four maneuvers per Starlink satellite every month.

The global space industry, however, is far from done with satellite constellation deployments. Analysts estimate that by 2035, tens of thousands more satellites might be added to Earth orbit. Things might therefore become much more treacherous in the not-so-distant future.

Lawler and Thiele declined to estimate how short the Crash Clock could be if there were perhaps six or 10 times as many satellites in Earth's orbit as there are today.

They say the satellite operators can, to a degree, improve their chances to survive solar mayhem by quickly de-orbiting old satellites and carefully considering how many spacecraft to launch to certain altitudes.

"The part that satellite operators can control is the number of satellites and the density of satellites," said Lawler.

Thiele added that the study highlights how fragile the space environment has become in a few short years.

"The Crash Clock demonstrates how reliant we are on errorless operations," she said. "If everything works as it's supposed to all the time, then we're okay."

Sooner or later, however, another Carrington-size solar storm will hit. Whether satellite operators will be ready for it remains a question. In 2025, the number of global space launches exceeded 300 for the first time in history, and the industry shows no signs of slowing down.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.