Could satellite-beaming planes and airships make SpaceX's Starlink obsolete?

"When the Stratomast is flying, all these old satellites are going to be in museums."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A new generation of stratospheric balloons and high-altitude uncrewed aerial vehicles (UAVs) could soon connect the world's unconnected with high-speed internet at a fraction of the prices commanded by operators of satellite megaconstellations such as SpaceX's Starlink.

High-altitude platform stations, or HAPS, have been around for a while, but the technology hasn't fully taken off yet. Google spent 10 years trying to develop balloons that would hover in the stratosphere above remote rural areas and beam internet to residents but abandoned that project, called Loon, in 2021, concluding that it couldn't be made sustainable.

Four years later, companies such as World Mobile Stratospheric and Sceye say they are on the verge of making internet-beaming from the stratosphere, the layer of Earth's atmosphere roughly 6 miles to 31 miles (10 to 50 kilometers) above the planet, a reality. Moreover, they claim that their offerings will be better and cheaper than that of satellite megaconstellations in low Earth orbit (LEO), which too have been developed with the promise of connecting the world's unconnected.

Richard Deakin, the CEO of World Mobile Stratospheric, said HAPS have failed to make it so far because they couldn't support power-hungry antennas needed to beam down high-bandwidth internet across vast swaths of land. Previously-tested high-altitude balloons and airships have relied on photovoltaics to generate power, which only provide "a couple of hundred watts," according to Deakin.

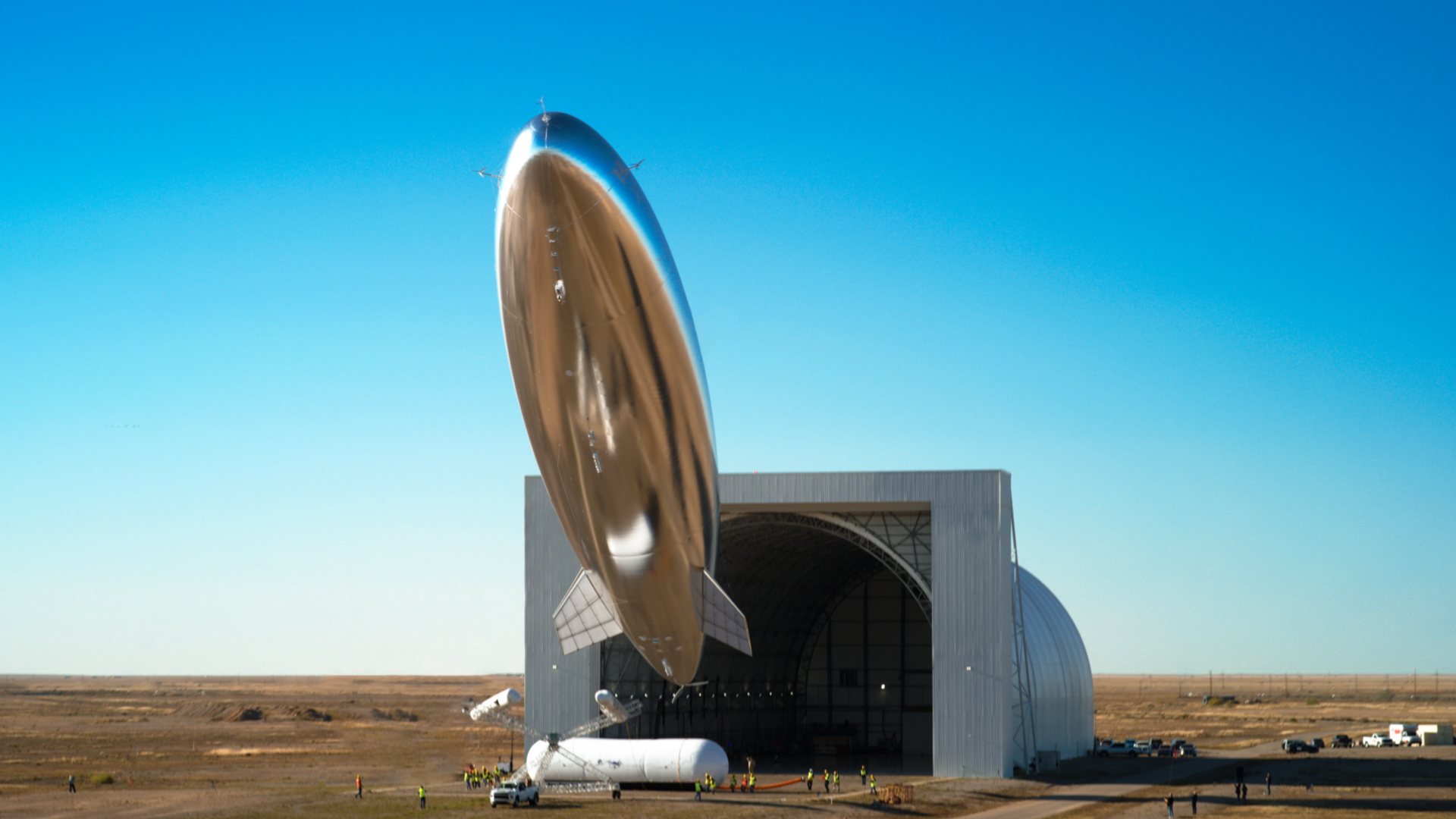

He said that his company's HAPS, an autonomous plane called the Stratomast, will be powered by liquid hydrogen, allowing it not only to hover for six days at an altitude of 60,000 feet (18 km), but also generate enough electricity to support a 10-by-10-foot (3 by 3 meters) phased-array antenna that could connect 500,000 users on Earth at the same time. After six days, a new aircraft would arrive to take over the service while the first returns to the base for refuelling.

Deakin says users will get 200 megabits per second (Mbps) of connectivity directly into their smartphones from Stratomast. That would be a vast improvement over Starlink's current direct-to-device offering of 17 Mbps, which is currently only capable of supporting emergency text messaging. Even AST SpaceMobile, which is building a constellation of giant orbiting antennas to beam internet directly to smartphone devices, can sustain only about 21 Mbps.

"When the Stratomast is flying, all these old satellites are going to be in museums," Deakin said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The 4-metric-ton (4.4 tons) Stratomast aircraft, made of lightweight carbon fiber, has a 184-foot (56 m) wingspan, equivalent to that of a 120-metric-ton (132 tons) Boeing 787 Dreamliner plane. A single Stratomast will cover an area of 6,000 square miles (15,000 square km). Such a wide reach means that the whole of Scotland could be covered with just nine Stratomast platforms, Deakin said. World Mobile Stratospheric estimates the cost of running such a system would be around just £40 million ($52 million US) per year, allowing the company to provide 200 Mbps of internet connectivity to Scotland's 5.5 million inhabitants at a cost at about 60 pence per person per month.

"That's enough for TV, computer broadband, the whole thing…,"Gregory Gottlieb, the head of aerial platforms at World Mobile, told Space.com.

In comparison, the cheapest Starlink subscription, only covering areas with low demand, currently costs $40 a month. And price is only one of the drawbacks of LEO satellite internet. To be able to connect to Starlink satellites, users need dedicated terminals. Although Starlink's downlink speeds reach up to 250 Mbps, the bandwidth gets diluted as the number of users grows. For example, troops on the frontline in eastern Ukraine complain that Starlink bandwidth limits the use of ground robots, as most terminals there only get about 10 Mbps.

"There really isn't any satellite constellation that can serve more than one person per square kilometer [0.4 square miles]," Mikkel Frandsen, the founder and CEO of another HAPS developer, New Mexico-based Sceye, told Space.com. "That's kind of the upper end."

Sceye, founded in 2014, has developed an airship-like HAPS powered by solar energy, which has already completed several successful test flights. In August last year, the Sceye airship became the first stratospheric platform that successfully survived a night in the stratosphere without sinking after sunset and remained in a required position above a fixed spot on Earth. The problem of drift and difficulties with station-keeping were among the issues that led to the demise of the Google Loon project, according to Frandsen.

In June, Sceye received a "strategic investment" from Japanese telecommunications operator SoftBank, which hopes the technology will allow it to provide next-generation connectivity to users even in the most underserved areas. Sceye also recently won a contract from NASA to host Earth-observation payloads.

Frandsen said that Sceye doesn't want to compete with satellite internet providers but thinks that megaconstellations, even when fully deployed, will not be able to satisfy the world's need for connectivity.

"All satellite constellations, when they're combined, will not do anything other than [make] a little dent in the global demand for connectivity," he said. "They're going to do fine business at the prices they're charging, but they're not going to serve billions of people. Space isn't all that scalable. They're going to serve millions of people."

LEO satellite megaconstellations such as SpaceX's Starlink orbit a few hundred kilometers above Earth's surface. In the past five years, they have replaced distant geostationary satellites, which orbit 22,236 miles (35,786 km) above Earth, as the dominant technology for delivering internet connectivity from space. But the growth in the number of satellites concerns space sustainability experts. The more objects hurtling around the planet, the higher the risk of collisions that could pollute near-Earth space with thousands of dangerous fragments. Moreover, atmospheric physicists worry about the growing amount of metal being burned up in the atmosphere during satellite reentries.

"HAPS are a really interesting domain because I think, in many ways, they cover the best of terrestrial and the best of satellite — high-altitude systems without suffering from the drawbacks," said Deakin.

Gottlieb said that HAPS could provide a convenient, flexible and easily replaceable alternative to satellite internet at times of growing geopolitical tensions.

"There is a view that, within 24 hours of any major conflict, low Earth orbit would be unusable for military purposes," Gottlieb said. "We can deploy aircraft at very short notice. We can be agile in terms of spectrum that we're using, and all sorts of different boxes that can go onto our platforms."

Deakin's team has been developing Stratomast since 2019 as part of a collaboration with German telecommunications provider Deutsche Telecom. During tests in Germany and Saudi Arabia, they demonstrated the workings of their novel antenna technology.

Earlier this year, the company was acquired by the U.S.-based telecom provider World Mobile. The company recently partnered with Indonesian telecommunications provider Protelindo to get Stratomast off the ground. The partnership plans to conduct flight tests with their antenna at a lower altitude next summer and hopes to begin stratospheric test flights in 2027.

Sceye, in the meantime, is working on increasing the endurance of its airship and hopes to commence commercial service in 2027.

Tereza is a London-based science and technology journalist, aspiring fiction writer and amateur gymnast. She worked as a reporter at the Engineering and Technology magazine, freelanced for a range of publications including Live Science, Space.com, Professional Engineering, Via Satellite and Space News and served as a maternity cover science editor at the European Space Agency.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.