This fleet of sungazing spacecraft could help spot 'space tornadoes' headed towards Earth

Four proposed sungazing spacecraft, working together, could help speed up space weather warnings by 40%, a new study suggests.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

A fleet of sentinel spacecraft, including one with a huge solar sail, could watch out for sneaky "space tornadoes" posing a threat to Earth during solar storms, a new study suggests.

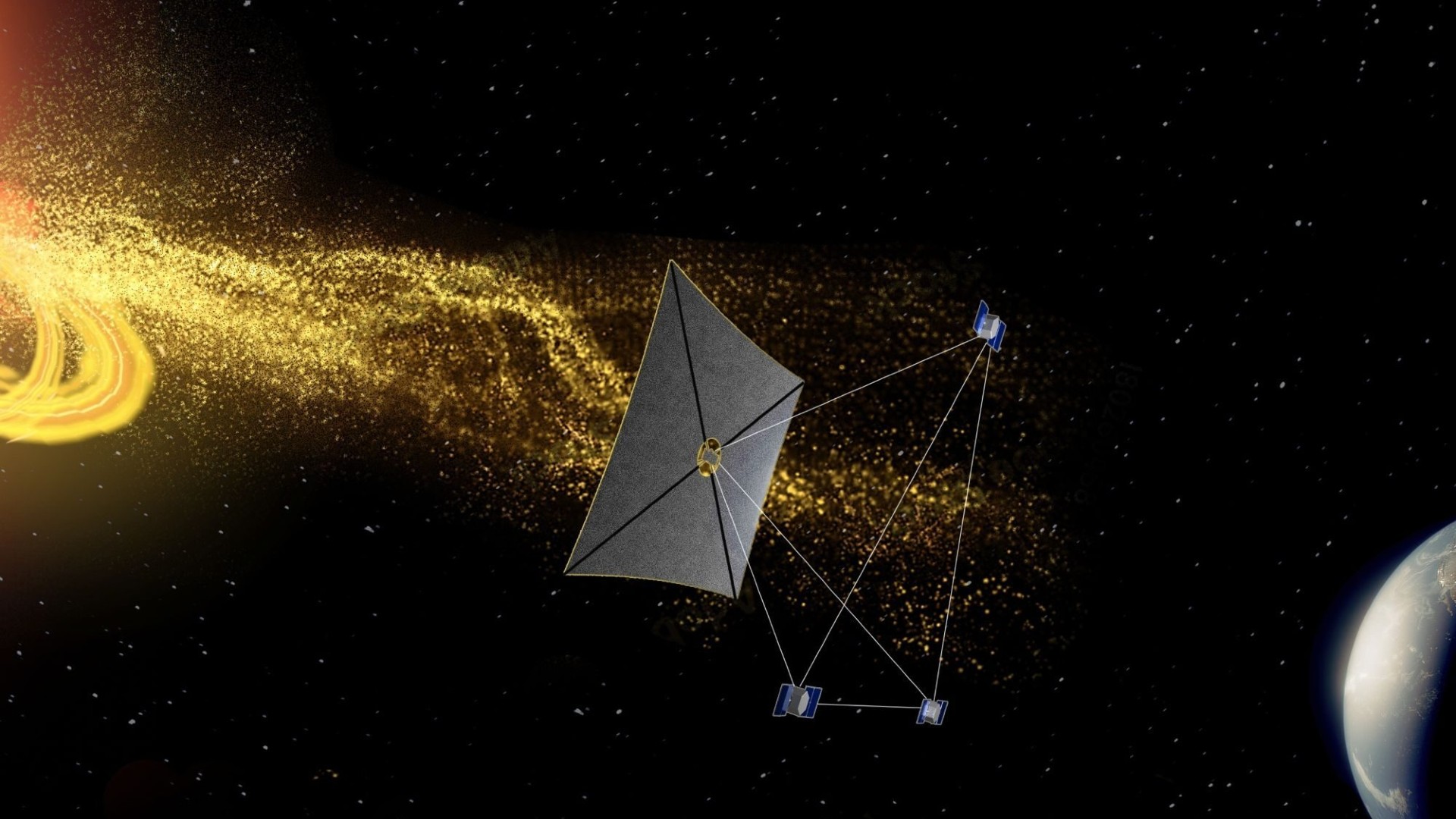

The proposal says that four deep-space spacecraft, collectively called Space Weather Investigation Frontier (SWIFT), could speed up "space weather" warnings by 40%. While three spacecraft would be powered by conventional fuel, the fourth would have a solar sail roughly a third of the size of a football field.

That gigantic sail is needed to stabilize the fourth spacecraft in an unusually difficult orbit that gives it a closer perch to view the sun's activities. But the work will be worth it, scientists emphasize: Faster warnings for powerful, tornado-like plasma structures emerging from the sun would in turn help protect satellites, power lines and other critical infrastructure from these solar eruptions.

These spacecraft are not funded, nor have they been formally designed, so there is no firm estimate about how soon they would launch or how much they would cost. But the proposal, outlined in a study published in the peer-reviewed Astrophysical Journal on Monday (Oct. 6), gives an idea of how they would work. (NASA and the National Science Foundation funded the study.)

To be sure, space agencies including NASA already have several sun-gazing spacecraft stationed to watch for solar activity. The sun is currently in a very active period in its 11-year cycle, increasing the frequency of solar flares and coronal mass ejections.

CMEs carrying electrons (charged particles) towards Earth can transfer more solar wind energy into the magnetosphere (a part of our atmosphere) under certain conditions, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) states.

If the flow of solar particles is strong, and if the magnetic field carried with the solar wind is flowing southward and opposite to Earth's magnetic field, "there is a transfer of more solar wind energy into the magnetosphere," officials wrote.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The energy from this solar wind can cause damage if it interacts with satellites or power lines — just like what happened in the province of Quebec in March 1989, during a solar storm that plunged thousands into darkness during winter.

Improving predictions requires observations, so NASA and the European Space Agency have spacecraft stationed at Lagrange Point 1 or L1 — a gravitationally stable orbit between Earth and the sun that uses a minimum of fuel.

But as the University of Michigan writes, these spacecraft can't see everything: "A solar eruption aimed away from Earth, or with northward-pointing magnetic fields, might still toss vortices with southward-pointing magnetic fields toward Earth. Those tornadoes would go unnoticed if they miss the probes stationed at L1."

The tornados are more properly called "flux ropes", and describe features as small as 3,000 miles long (4,828 km) and as vast as 6 million miles (9.5 million km) wide. (For comparison, the distance between Earth and the sun is roughly 93 million miles or 150 million km). The tornadoes are hard to even simulate: too small for CME studies, but too large for probes of magnetic fields and plasma particles.

The new study, which researchers described as "unprecedented" in its resolution, includes simulations showing how tornados may arise. The sun is always sending out a "solar wind" of charged particles across the solar system, but a CME ejection is faster than that.

As a speedy CME pushes its way into the slower solar wind, the wave of faster-moving particles can shove aside "spinning masses of plasma, like a snowplow tossing snow," according to the study. Some of these masses do fall apart quickly, but some persist as "tornadoes".

The study says the proposed four-spacecraft constellation could spot these tornadoes on the fly. Scientists from the University of Michigan are leading the proposal, which would put the four machines into a flying formation shaped like a pyramid. Each side of the "pyramid" would be roughly 200,000 miles (322,000 km) long, which is nearly the average distance between Earth and the moon.

The study suggests placing one spacecraft in each of the three corners of the pyramid's base, which would be arranged on a plane (a virtual, flat surface) around L1. The fourth spacecraft is a bit of a special case. It would serve as a "hub", and would be situated beyond L1 and facing toward the sun.

That location beyond L1 is too unstable for the fourth spacecraft to use fuel to stabilize itself, but it could use a huge, aluminum solar sail that is about a third of the size of a football field. But that's assuming the success of a predecessor project for this sail concept, called Solar Cruiser. NOAA and NASA hope to get a rideshare launch for that spacecraft in 2029.

In theory, that sail size is enough to "catch enough photons to maintain the spacecraft's position, without burning fuel," the university wrote. "This configuration," officials added, "would allow SWIFT to see how the solar wind changes on its way to Earth, and its hub closer to the sun could make space weather warnings 40% faster."

And the team emphasized how important these spacecraft would be in finding tornadoes: "Our simulation shows that the magnetic field in these vortices can be strong enough to trigger a geomagnetic storm and cause some real trouble," added lead author Chip Manchester, a research professor of climate and space sciences and engineering at the university.

Elizabeth Howell (she/her), Ph.D., was a staff writer in the spaceflight channel between 2022 and 2024 specializing in Canadian space news. She was contributing writer for Space.com for 10 years from 2012 to 2024. Elizabeth's reporting includes multiple exclusives with the White House, leading world coverage about a lost-and-found space tomato on the International Space Station, witnessing five human spaceflight launches on two continents, flying parabolic, working inside a spacesuit, and participating in a simulated Mars mission. Her latest book, "Why Am I Taller?" (ECW Press, 2022) is co-written with astronaut Dave Williams.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.