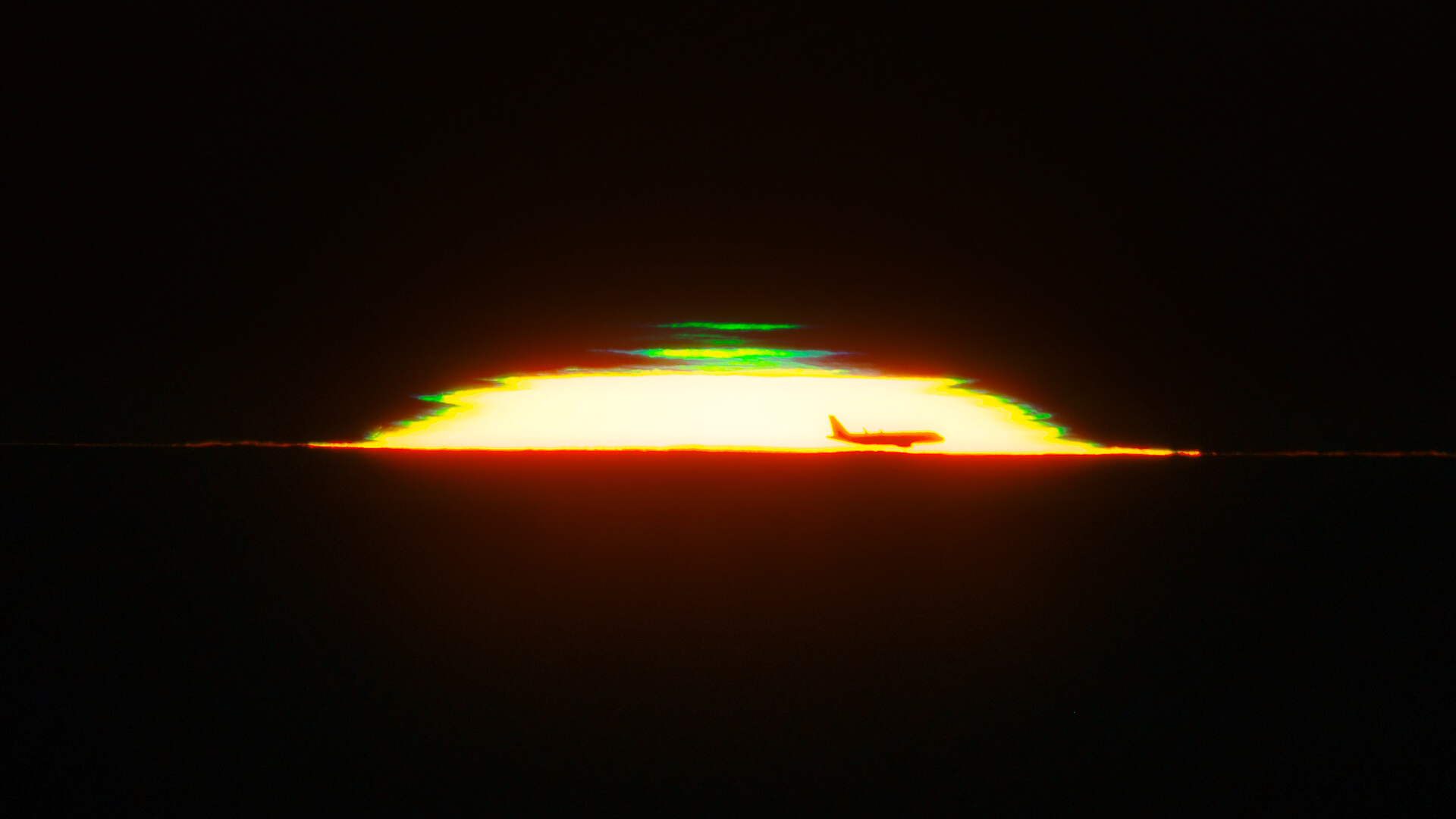

A green flash at sunset | Space photo of the day for Dec. 8, 2025

This rare phenomenon is also called the green rim and it actually happens at every sunset.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Just as the sun slips behind the Chilean Andes, it seemed to send up a tiny emerald flare. The photograph, taken from Cerro Pachón in Chile by NOIRLab Audiovisual Ambassador Petr Horálek, captures a classic but elusive atmospheric trick of the light: the green flash.

What is it?

Despite the dramatic name, a green flash isn't an explosion or a burst of energy. It's simply sunlight being bent and split by Earth's atmosphere.

White sunlight is made of all the colors of the rainbow. But as Earth rotates and the sun approaches the horizon, its light has to pass through a very thick slice of the atmosphere. That air acts like a giant prism, refracting (bending) the light slightly and separating colors based on their wavelength. Shorter wavelengths — blue and green — are bent more strongly than red and orange.

At the very last moment before sunset (or the first moment after sunrise), the sun's disk is already mostly hidden below the horizon. What you're seeing is really a stack of slightly displaced images: the "red sun," the "orange sun," the "yellow sun," and so on, all shifted by tiny different amounts. The lower colors disappear first. For a brief instant, the uppermost surviving layer is dominated by green, forming a thin glowing band at the top edge of the sun: the green rim. If the conditions are just right — clear air, a sharp horizon, the right layering in the atmosphere — that skinny rim looks like a small, detached green spark: the famous green flash.

In reality, a green rim is there at every sunset. It's just usually so thin, and so brief (a second or two), that our eyes can't pick it out. Sensitive cameras, high-quality lenses, and fast bursts of images are perfect for catching it.

Where is it?

This image was taken on Cerro Pachón in Chile.

Why is it amazing?

There are lots of reasons that scientists are interested in atmospheric optics like this. The shape, height, and duration of a green flash depend on how temperature, pressure, and density vary with altitude. Layers of warm and cool air can act like stacked lenses, creating mirage effects and stretching or squashing the sun's image. By modeling and measuring green flashes carefully, scientists can test how well we understand the vertical structure of the atmosphere near the horizon.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Telescopes on Cerro Pachón, where this image was taken, and other mountaintops look through the same atmosphere that creates the green flash. The air bends different colors by different amounts, slightly smearing out starlight into a little rainbow. Instruments called atmospheric dispersion correctors are designed to counteract that effect. Understanding exactly how Earth's atmosphere splits and bends light — the same physics behind the green flash — helps astronomers sharpen their images and spectra of distant stars and galaxies.

Want to learn more?

You can learn more about the green flash and Earth's atmosphere.

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is the Content Manager at Space.com. Formerly, she was the Science Communicator at JILA, a physics research institute. Kenna is also a freelance science journalist. Her beats include quantum technology, AI, animal intelligence, corvids, and cephalopods.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.