Seeing a bull's-eye in the desert | Space photo of the day for Dec. 5, 2025

Is this really a crater in the Saharan Desert?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

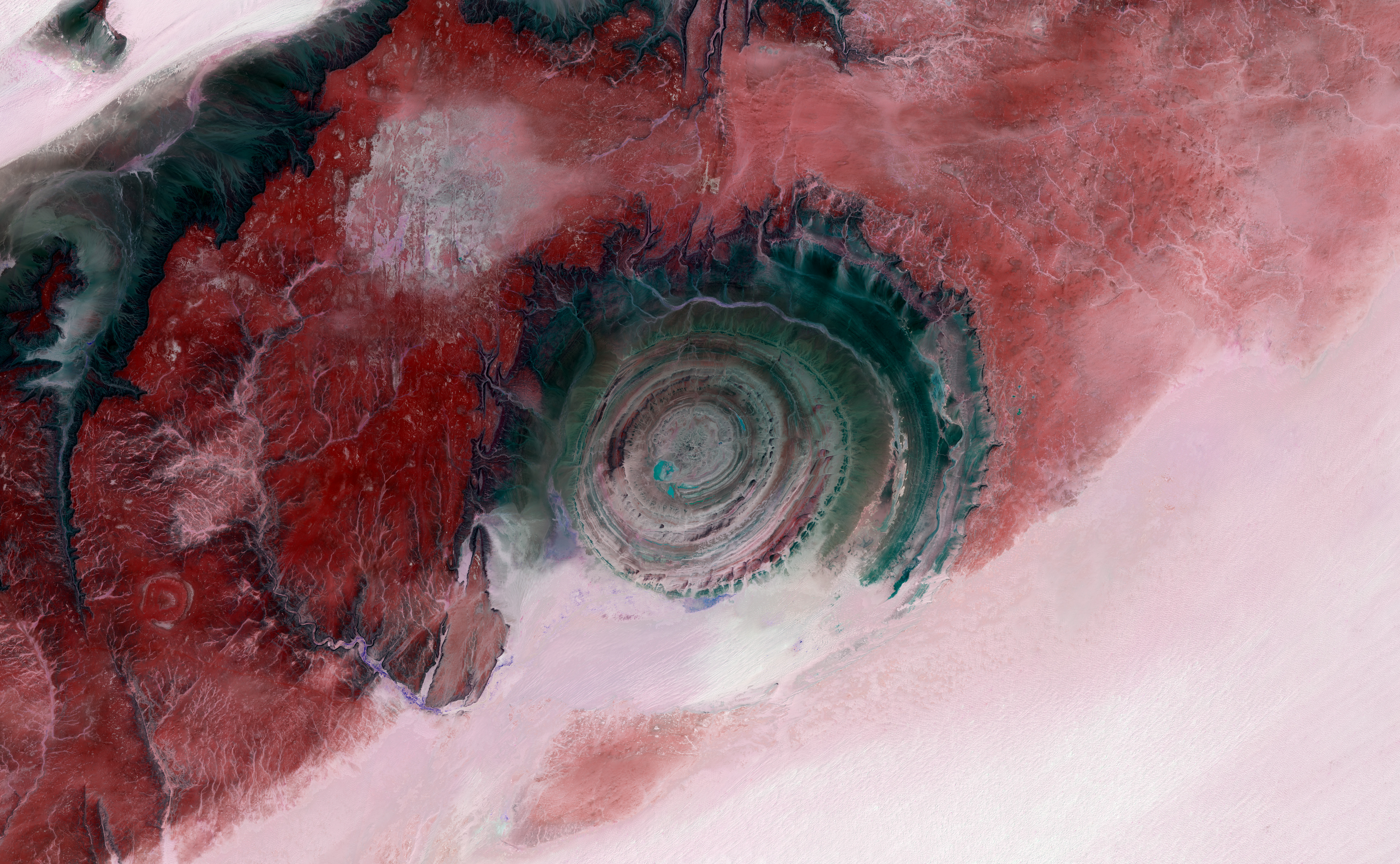

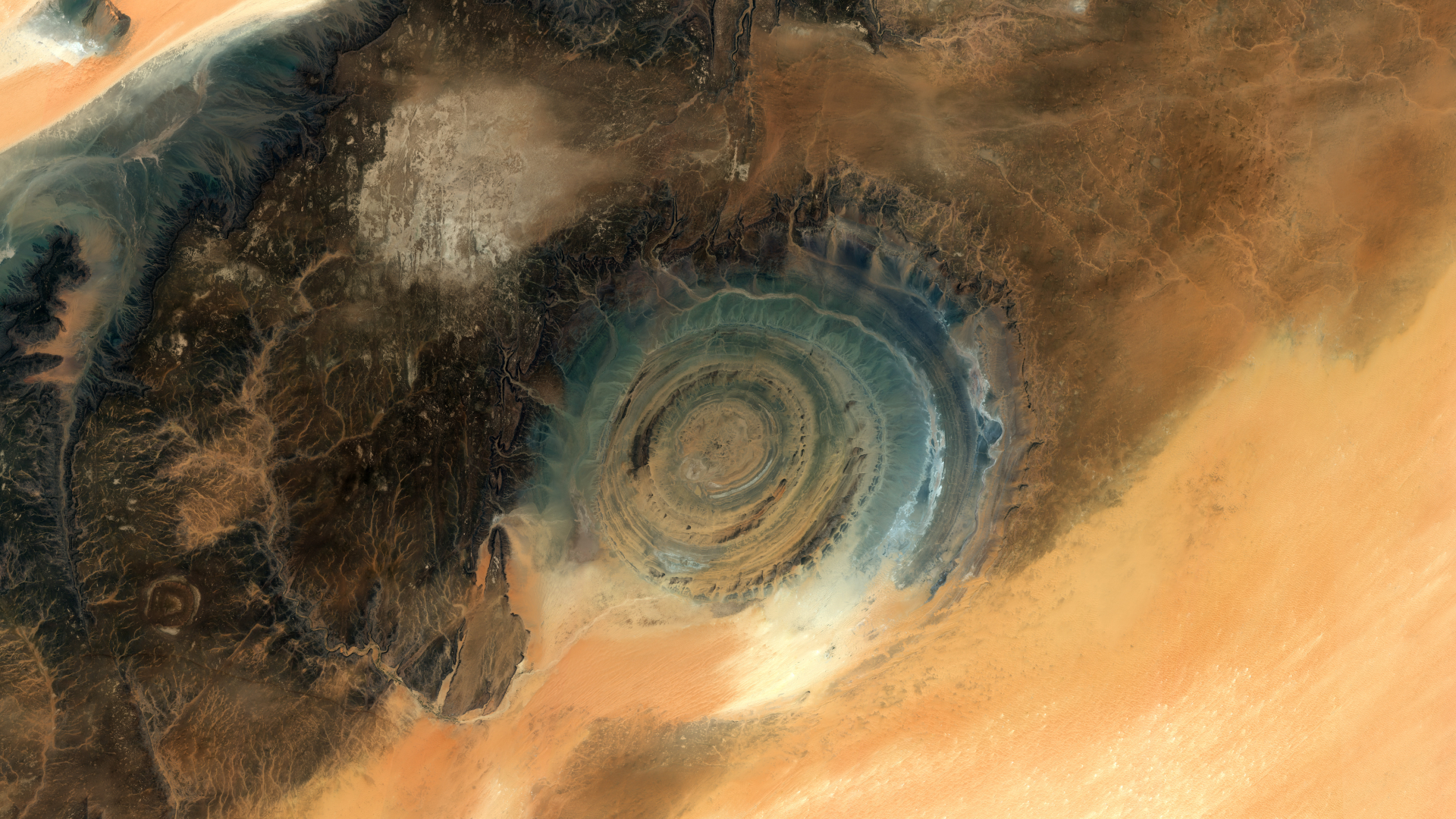

In the middle of Mauritania's Sahara Desert, surrounded by an ocean of sand, lies a colossal stone spiral that seems almost too perfect to be natural. From orbit, in a recent image taken by the European Space Agency's Copernicus Sentinel-2 satellite mission, it looks like a target etched into the desert: the Richat Structure, better known as the Eye of the Sahara.

What is it?

The Richat Structure spans around 31 miles (50 km) across, large enough to be a clear landmark for astronauts passing overhead.

On the ground, its rings are hard to appreciate; dunes, heat haze, and uneven terrain all conspire to hide the full shape. But from space, especially in the images taken by the Copernicus satellite, the structure appears as a set of concentric circles, like ripples frozen in rock.

For years, its near-perfect circle led scientists to suspect a dramatic origin: a meteorite impact. A formation that round, in the middle of nowhere, had to be a crater — or so it seemed.

Where is it?

This image was taken over the Adrar region of northern Mauritania.

Why is it amazing?

Further fieldwork and analysis overturned the impact crater theory, as researchers found no signs of shocked quartz, melted rock, or other telltale traces of a high-energy collision. Instead, the Richat Structure turned out to be something more subtle and, in many ways, more impressive: a deeply eroded geological dome.

Millions of years ago, a large bubble of molten rock pushed up beneath the surface, gently doming the overlying sedimentary layers. Over time, wind, water, and sand did what they do best in the Sahara: sandblast and carve away the softer rocks. Harder rocks, like quartzite-rich sandstones, resisted erosion and remained as high ridges, while the softer layers between them were worn into valleys.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The result is a natural cross-section of Earth's crust, peeled back in rings. The outer rings mostly consist of more erosion-resistant rock, while the interior exposes older layers that once lay deep underground. Geologists estimate that parts of this structure are at least 100 million years old.

In the false-color composite images from the Copernicus satellite mission, the story of the landscape becomes much clearer as specific wavelengths of light are combined to highlight different materials and surface features: the tougher quartzite sandstones appear in shades of red and pink, tracing the outer rings and inner ridges; darker patches between these rings mark zones of softer, more eroded rock; and tiny purple specks in the southern part of the structure reveal individual trees and bushes following a dry riverbed that snakes into the Eye. From the vantage point of Earth orbit, the Eye continues to stare back at us: a giant geological bull's-eye, etched into the Sahara, quietly recording a deep history of Earth written in stone.

The image shows the difference in temperature between the top of a hurricane and the bottom.

The images reveal the storm's incredible power and offer vital insights into how such hurricanes form.

A powerful geomagnetic storm created a series of brilliant auroras recently for observers across North America.

Want to learn more?

You can learn more about Earth-observing satellites and the Copernicus program.

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is the Content Manager at Space.com. Formerly, she was the Science Communicator at JILA, a physics research institute. Kenna is also a freelance science journalist. Her beats include quantum technology, AI, animal intelligence, corvids, and cephalopods.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.