Native artists in Texas and Mexico shared their vision of the universe for 4,000 years, ancient murals suggest

The term cosmovision refers to a conception of the universe in totality.

Archaeologists often seek to understand ancient cultures by studying images left behind on rock faces. While these images vary widely, they're a global phenomenon. In fact, petroglyphs and painted murals created by past societies have so far been found on every continent, except Antarctica.

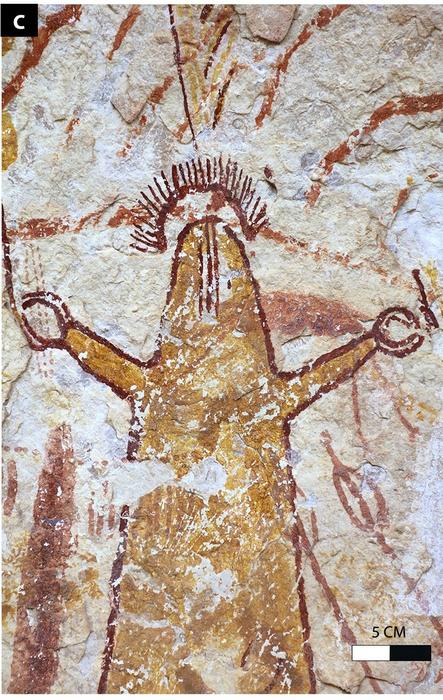

And, in a new study, researchers say they’ve found evidence of consistent imagery on cliff faces, caverns and natural recesses in 12 sites in the Lower Pecos Canyonlands — an archeological region in southwestern Texas and Northern Mexico — providing evidence of consistent themes in the murals across 175 generations. They say this continuity suggests that, in both regions, hunter-gatherers' conception of the universe — which the team calls their "cosmovision" — stayed largely the same across roughly 4,000 years.

They also suggest that, due to the style and iconographic similarities, the paintings were used to transmit important information across thousands of years.

In modern times, the style of the paintings is called 'Pecos River style' (PRS). "We propose that Pecos River style paintings […] faithfully transmitted a sophisticated metaphysics that later informed the beliefs and symbolic expression of Mesoamerican agriculturalists," the authors write in the research paper.

Measuring time

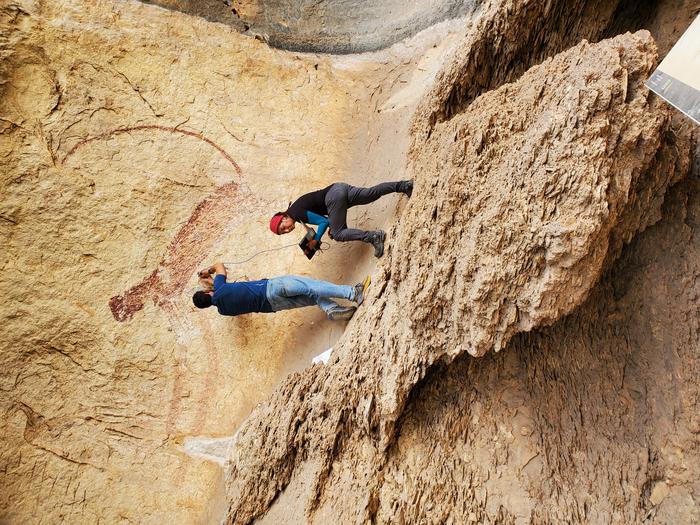

To find out when the murals were created, the researchers used a pair of dating methods — radiocarbon dating and oxalate dating. They used the dating to create a "chronological model" for the paintings, relying on 57 direct radiocarbon dates and 25 oxalate dates across the 12 sites.

"Establishing the temporal context of PRS is a prerequisite for leveraging the full interpretive potential of this sophisticated iconographic system," the authors write in their paper.

The team used radiocarbon dating of organic carbon in the paintings, as carbon isotopes in organic matter break down over time. By measuring this decay, archaeologists can get fairly precise dates for the age of the paint used in the murals.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"North American Indigenous groups used fat in deer bone marrow as a binder to adhere mineral pigment particles together and saponin-rich plants, such as the C3 Yucca constricta, as a vehicle or emulsifying agent," the authors write.

With oxalate dating, the team measured the age of oxalate mineral accretions above and below the paint. The difference in the ages of the accretions supported the radiocarbon dating of the layers of paint.

With these dating methods, the researchers figured out that the paintings — and their similarities — stretched over thousands of years.

Knowledge transmission

Archeologists study ancient rock art, which includes paintings on rock (pictographs) or peckings in rock (petroglyphs) to learn about the cultures of ancient peoples. Many scientists have interpreted cosmological meanings in these images, like solar eclipses and supernovas.

However, deciphering the meaning that ancient and prehistoric civilizations ascribed to the pictographs and petroglyphs they created long ago isn't an exact science; it’s interpretation.

The similarities in the rock murals that were painted across thousands of years may suggest they were used to transmit important knowledge through many generations.

"Eight of the 12 murals, created at different times, all adhered to the same compositional guidelines, such as the sequential application of color," the authors write. "These eight also all contained the same iconographic vocabulary, representing a continuity in cultural cosmovision."

While the study relies on previous studies that have found parallels between the images in rock paintings and cosmological concepts, the authors say that "these interpretive studies are contributing to ongoing discussions into the existence, distribution and antiquity of a pan-Mesoamerican or perhaps pan-New World cosmovision."

A study about these results was published on Nov. 26 in the journal Science.

Julian Dossett is a freelance writer living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He primarily covers the rocket industry and space exploration and, in addition to science writing, contributes travel stories to New Mexico Magazine. In 2022 and 2024, his travel writing earned IRMA Awards. Previously, he worked as a staff writer at CNET. He graduated from Texas State University in San Marcos in 2011 with a B.A. in philosophy. He owns a large collection of sci-fi pulp magazines from the 1960s.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.