The 'ultraview effect': What happens when we bring human spirituality to outer space?

Can traveling to space change a person's religious views or spiritual outlook?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

No one can say with scientific confidence why we exist or what happens when we die. In fact, scientists have a tenuous grasp on what it even means to be conscious. But our purely human urge to ask the big questions about our existence — one dependent on Earth-creature comforts like oxygen, gravity and water — is one of our reasons for leaving life as we know it and exploring outer space.

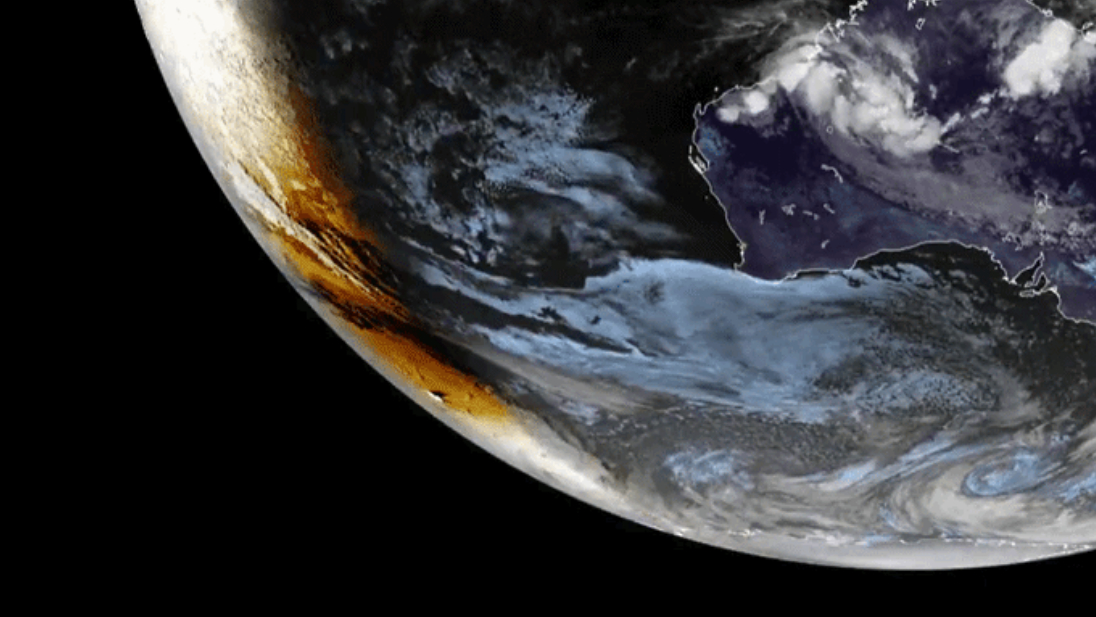

But how do the relatively few people who were able to leave Earth feel about those big, existential questions? By some accounts from those who've returned from orbit, the newfound perspective is so awe-inducing there's a name for it: the "overview effect", a term coined by Frank White, a space philosopher who wrote a book with the same name. In a nutshell, the overview effect describes a strong feeling of connection and protection over Earth and everything on it, reported by some astronauts after looking down at the blue marble from space.

But there's a separate sense that captures what happens when astronauts look the other direction from a spacecraft — not towards Earth but toward the overpowering sheath of stars — called the "ultraview effect." Coined by Deana Weibel, an anthropologist at Grand Valley State University who studies religion and has interviewed retired astronauts as well as other space crew members on their beliefs and experiences, Weibel says the ultraview effect appears to be a more unsettling perspective shift that results from specific visual conditions in the spacecraft and a bright wall of stars.

Writing in a 2020 article in the journal "Religions", Weibel argued that, compared to the overview effect, the ultraview effect is "much less about an intensified feeling of connection to and protectiveness of our planet, and more about a very real sense of the limitations of what we know compared to the vastness of what we don't know."

Anyone who's dedicated themselves to a meditative practice, had a meaningful psychedelic "trip" or dabbled in any other experience that shifted your perspective in how you see yourself in the grand scheme of the universe, the fact that astronauts blasting off into literal outer space may sometimes report back experiences akin to ego death probably isn't surprising, or maybe even sounds redundant.

But as we continue to explore space, we'll continue to study its effects on human health, which includes mental health and the elusive experience of human consciousness. And as we bring more human consciousness to space, we'll bring with it old religions and new names for spiritual experiences in space.

Can (or should) astronauts be spiritual?

There's a common belief that space science (or science in general) and religiosity are mutually exclusive. This line of "faith vs. science" has been made firmer in recent years, as religion has been used as one tool of many to discount evidence-based findings as they relate to vaccines, climate change and more scientific issues that have been made politically partisan.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

But faith and U.S. space exploration have a history together as long as NASA is old. In the great space race of the 1950s-1970s, the state-proclaimed atheist country of Russia was battling the U.S., a state-proclaimed secular nation that was still very much religious in much of its iconography and customs. As science and religion historian Adam Shapiro argued in an article for Undark, the religious discrepancy and idealism was used to inspire more support and triumph in the U.S. for its wins, and used as a point to gloat on the Soviet side.

But even in the atheist Soviets, there was behavior that could be considered ritual, or even magical. As detailed in a paper she co-wrote with Glen Swanson, an ex-historian for the Johnson Space Center and her husband, Weibel outlined some of the rituals Soviet astronauts would partake in before spaceflight, including specific places to urinate. Instead live in the gray area that's inherently human: a blend of science when we're able to know what's going on, and some magical thinking when we have no control. While not directly religious, such behavior also isn't scientific and mirrors a hard-to-track, even harder-to-define trend in people identifying as spiritual, not religious.

Weibel, following her interviews and observations, believes that the same gray area extends to astronauts: some are openly religious, some are atheists, others agnostic and more.

"There are different ways of being religious, right?" Weibel said. "So you can identify very strongly with the religion you grew up with, and the people in that religion, and not necessarily believe it." She added that even some astronauts who "straight-up" describe themselves as atheists have brought objects associated with their childhood or ancestral religion to orbit as a way of connection.

"That being said, a good solid core of the astronauts I've spoken to have been religious, and I think a lot of it has to do with the sort of traditional trajectory from military to NASA," Weibel said, where there are "churches on site" — a Catholic one or a Protestant one. Additionally, the astronauts initially recruited for space flight when it first began were white, Christian males. This year after President Trump took office for his second term, funding for NASA has been slashed, including for programs meant to recruit astronauts and scientists from more diverse backgrounds.

The 'ultraview effect' and what happens when you look the other way

According to Weibel, there are two ingredients you need to achieve the ultraview effect: the lights turned off in the spacecraft — it needs to be dark enough so you become "dark adapted" — and you need to have the time away from other duties and tasks to be able to look out the window, not at Earth but at the stars. The people who've been able to do this — just two, by Weibel's interviews — use similar language to describe a wall or sheet or stars.

One astronaut who inspired the "ultraview effect" term for Weibel is an Apollo crewmember in his 80s, referred to as "Zack" in the Religions article. He spent several days in orbit while the rest of the crew walked the moon below. This provided him with a little more time to become dark-adapted, and to look out at the galaxy to see a "sheet of light," which is something he told Weibel he "was not ready for."

"I don't know whether you'd call it spiritual or not, but when I saw the starfield out there in a way that nobody else has ever seen … I had some pretty profound thoughts," Zack is quoted as telling Weibel. "We are not unique in the universe."

Once back home on Earth, Zack — who Weibel describes as a "rational person, successful author and businessman" — wrote poetry to process his experiences of outer space and infinity. His experiences led him to modify some beliefs you'd maybe expect from a more "mid-line" Protestant upbringing, Weibel wrote, to less conventional beliefs including the potential for Earth's prior contact with alien life.

"We are not unique in the universe," Zack told Weibel. "I happen to believe we came from somewhere else."

Given the relatively small sample size including in Weibel's research, and the difficulty of replicating the ultraview effect on Earth, there are obvious limitations to claiming the experience as being a standard astronaut experience, or even claiming it's not a cumulative symptom of social isolation, stress or other factors astronauts confront in microgravity. But it opens the door for more speculation, study and interest in how human consciousness responds to space travel and contact with the stars we can't get in pictures.

Recreating space revelations on Earth

Of the overview effect and renewed commitment to the preciousness of life on Earth, an astronaut Weibel spoke with called "Beverly" said that going to space and viewing our planet from above didn't leave her with any type of profound sense she didn't already have.

"You don't have to go to space for this," she told Weibel in the Religions article. "I want my children to understand that."

"They might not ever get to go to space, but I don't want them to have to think, 'Oh I have to go to space to be able to appreciate that.'"

Correction 10/6: Deana Weibel is affiliated with Grand Valley State University. This article has been updated to reflect that.

Jessica Rendall is a reporter based in Brooklyn with a special interest in what keeps humans healthy — both on Earth and in space. Previously, she was a staff wellness writer at CNET and a freelancer who covered public health, music and lifestyle. She studied journalism at the University of Missouri and enjoys watching movies with subtitles on.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.