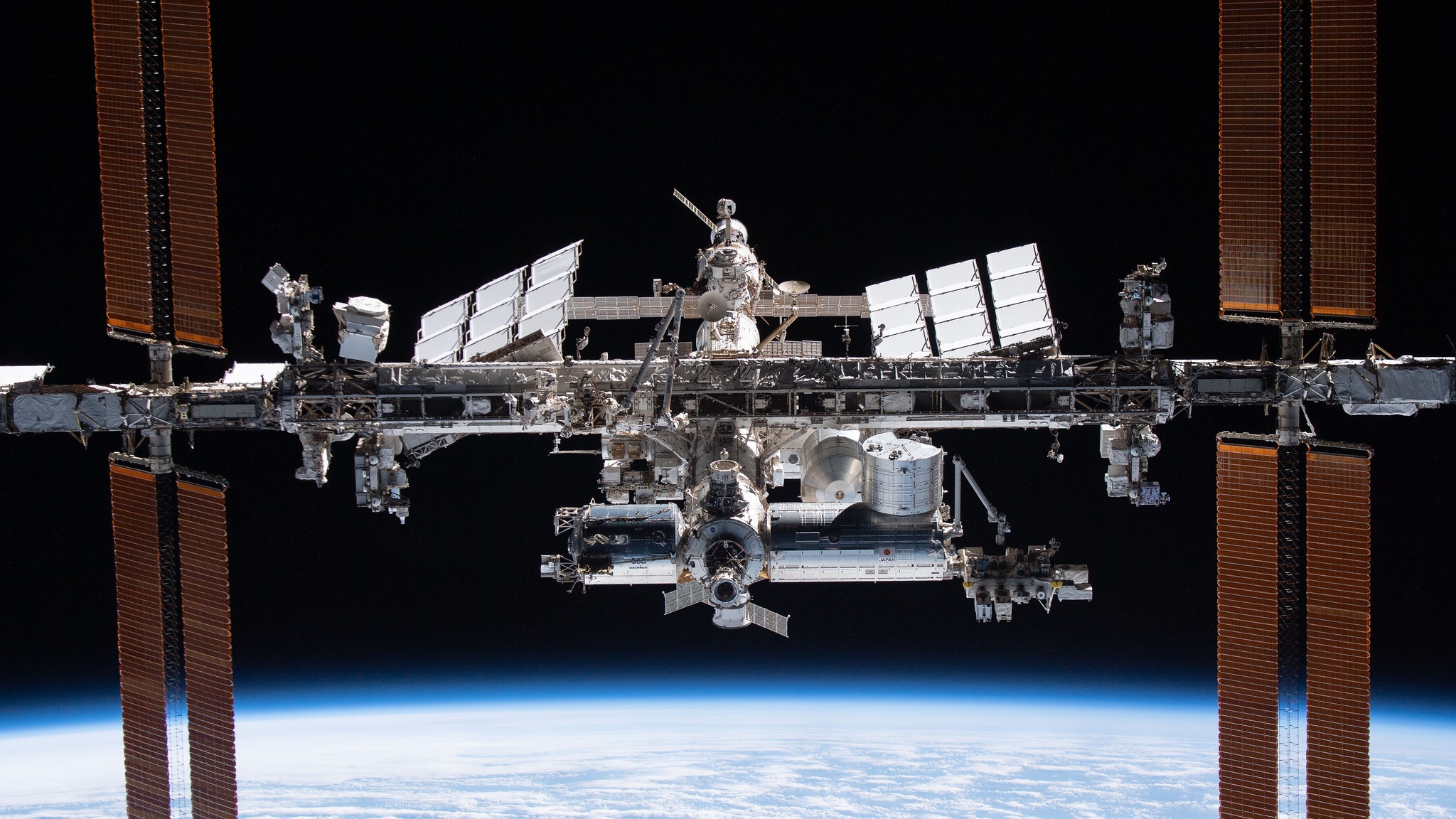

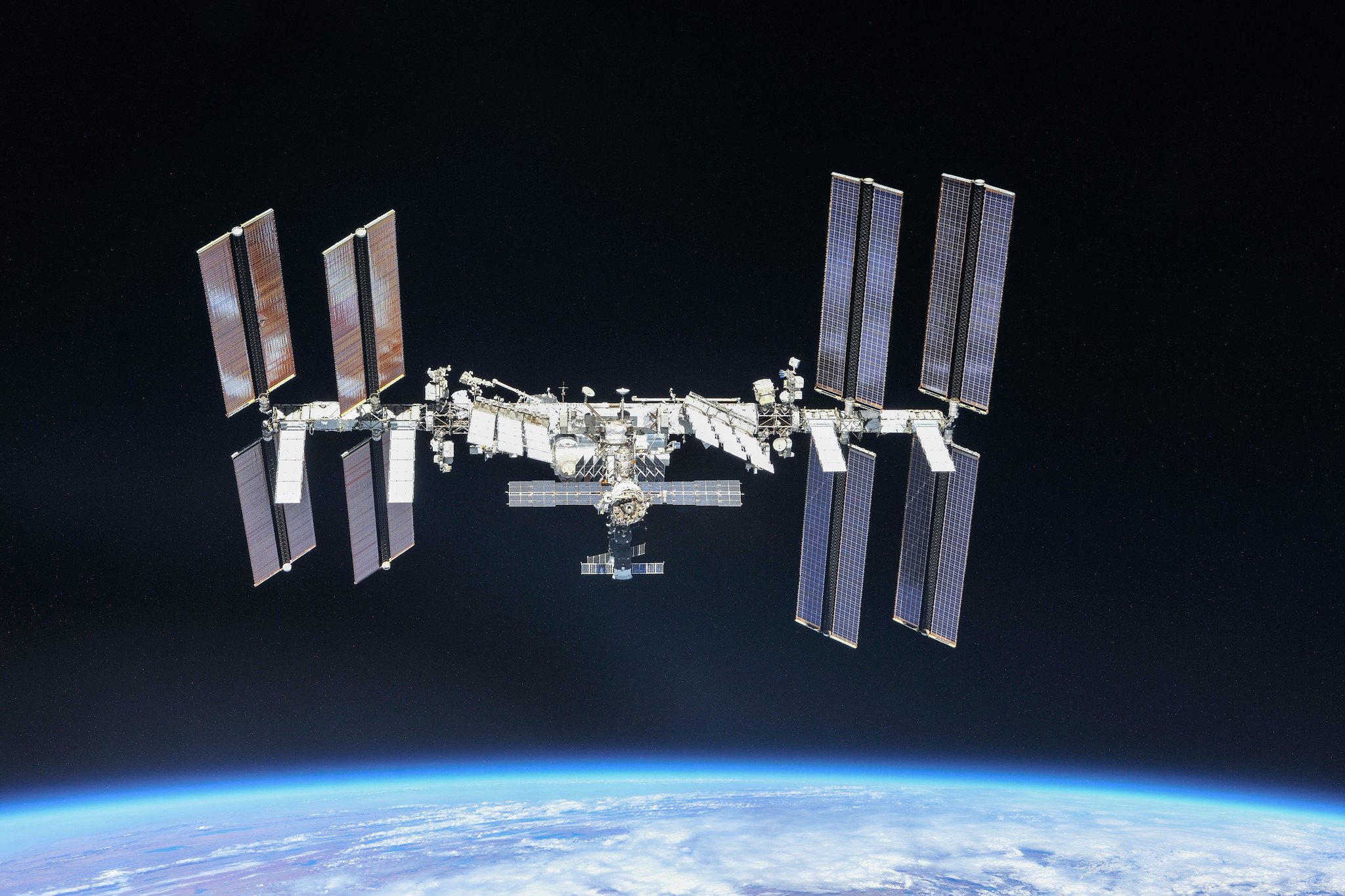

The International Space Station will fall to Earth in 2030. Can a private space station really fill its gap?

"He looked me straight in the eye and said, 'the space station is the experiment.'"

When the International Space Station plunges to its fiery doom in 2030, its loss to science will be incalculable, even if it remains an open question as to whether its successes matched humanity's ambitions for it.

By the time that the International Space Station (ISS) is safely and deliberately de-orbited over the Pacific Ocean, the station will have been permanently crewed for 30 years — it has had visitors ever since the first Expedition 1 mission (consisting of one astronaut and two cosmonauts) first docked with the fledgling, half-built station on November 2, 2000. Yet as we begin to near the end of the ISS's time in low Earth orbit, we are beginning to think ever more about the station's true legacy, whether it achieved what it set out to achieve, and what we will lose when it is finally gone.

The loss of the ISS will be keenly felt by many; it will be like when one of our beloved Mars rovers falters and is forced to end its mission. Sure, there will be other Mars rovers after, but they will be different. There will be other space stations, but they will be different.

For some, though, says sociologist Paola Castaño-Rodriguez of the University of Exeter, the end of the ISS will be no loss at all, as they always saw it as a white elephant.

"When it comes to spaceflight, everybody uses the word 'we,' but when you're a sociologist, the first thing you ask is, who is 'we?'" she told Space.com. "Just as equally as you have enthusiasts, there's a lot of people for whom this is an obscene waste of money."

Castaño-Rodriguez studies the processes by which science is conducted on the ISS, the unique way in which people from across the world come together to perform this science, and the different criteria by which this science is valued. She's also currently working on her book, "Beyond the Lab: the Social Lives of Experiments on the International Space Station," which explores these topics through the stories of three science experiments: the first time lettuce was grown on the ISS, the twin experiment involving Mark and Scott Kelly, and the Alpha Magnetic Spectrometer particle physics experiment affixed to the exterior hull of the ISS.

The critics are correct that the ISS is expensive, having cost $150 billion to build and operate so far, with NASA alone spending $3 billion per year to maintain it. For that amount of money, it doesn't seem unreasonable to expect some major outputs. Indeed, the science case for building the space station back in the 1990s was that the experiments that could be performed on the ISS could help cure cancer or discover dark matter.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"In a way, part of the problem is in how the space station was pitched, with these big promises that scientists had to make to get funded, and the issue is that those things have become the things that the space station is accountable for," said Castaño-Rodriguez.

The point is, the way we judge what we will lose when the ISS is de-orbited will differ depending on who is doing the judging — and how that judgement is cast. Looking at things purely from the eureka moments of scientific discovery that make headlines, people might consider the ISS a disappointment. Still, earlier this year, NASA has revealed that over 4,000 science experiments have been conducted on the ISS over the past 25 years, resulting in 4,400 scientific papers — but those findings have been, for the most part, relatively modest or incremental rather than revelatory.

However, looking at science in only this way would completely ignore what Castaño-Rodriguez considers to be the true success of science on the station, and what will be most keenly felt when it is lost.

"It takes for granted all the infrastructural work, all the operations, all the processes that, to me, are actually the key outcome of the space station, which is learning how to do science in such an adverse environment," she said. "In a way, it requires re-educating audiences about what is valuable about science. It's not just the shiny headline discovery, it is all the knowledge that is produced to enable a field to move forward. It's an epic and incredibly complex process to do these experiments on the space station.

"I think, when it comes to further space exploration, this infrastructural knowledge is going to be needed. There will be gaps and it is uncertain at the moment how they are going to be filled with other platforms."

Those other platforms that Castaño-Rodriguez refers to are commercial space stations NASA expects to replace the ISS. Companies such as Axiom Space, Blue Origin and a partnership of Starlab Space and Northrop Grumman have signed Space Act agreements with NASA to design and build new space stations. However, with this commercialization comes uncertainty about how much of what the ISS did will be transferred over to the new, privately developed orbiting habitats.

On the one hand, much of the expertise in these commercial ventures is from ex-NASA spaceflight people, and so rather than lose their expertise when the ISS is de-orbited, the processes and values that they embodied at NASA will be merged into the identity of the new commercial stations.

But on the other hand, commercialization could bring with it a loss of transparency.

In the United States, the direction of centrally funded science is governed by the peer review process of the National Academy of Sciences' decadal surveys. It is this process that guides what research NASA funds on the space station, which ensures that science on the ISS is judged only on its scientific merits.

"Are private companies going to be accountable to things like the decadal surveys?" asked Castaño-Rodriguez. "In terms of the process by which experiments will be selected, that's a big question, because the implication is that scientists just become the paying customers and the only experiments that go to the station are the ones that can be afforded."

Science today on the ISS is a truly public affair, with a mandate to make all the data collected by science experiments performed on the space station available in a public repository.

"This is a huge deal because you don't have to be involved in spaceflight to analyze the data," said Castaño-Rodriguez. "This open science is very much part of the space station's history that is not really talked about much, but it's a really important infrastructural aspect that is very international with researchers all over the world participating and engaging and re-analyzing the data produced on the space station."

The risk is that the transition from the publicly funded ISS to commercial stations could see the loss of this accessible open data, though Castaño-Rodriguez sees some reasons for optimism, for example through ex-NASA staff who, in the past, have championed open data and who now work for the private companies.

Castaño-Rodriguez also thinks commercial stations could be just as international as the ISS.

“They're going to be pathways to a lot of middle- to high-income nations to start paying for their astronaut missions," said Castaño-Rodriguez. For example, Axiom Space has already flown two Saudi astronauts on one of their missions (previously NASA had flown a Saudi prince on shuttle Discovery in 1985) as well as the first Turkish astronaut.

However, there's a difference between being a paying guest and a true partner, which is how the mix of international astronauts on the ISS has mostly been seen.

“I don't think [the commercial stations] will be anything like the particular international configuration of the ISS,” said Castaño-Rodriguez. "It's very much a product of its time."

That time being the 1990s and 2000s, off the back of the nearly five-decade Cold War and the dawn — arguably a false one — of renewed international cooperation both on Earth and in space. Militarily trained astronauts on both sides began shaking hands with people they'd been ideologically trained to treat as enemies. At the level of crew-member interactions, mission-control interactions, and scientific interactions, cooperation in space on the ISS helped break down barriers.

When we lose the ISS, we won't just lose its hardware, or how it made science in low-Earth orbit accessible. We'll also lose a pillar of space history that brought together people from different countries that were still learning to trust each other. Even today, despite Russia's invasion of Ukraine and tension that globally arose from the conflict, cosmonauts still fly to the station and work closely with their crewmates from other nations. It's hard to see that being replicated on a commercial station in today's geopolitical climate, at least to the same level and for such a prolonged time as it was exhibited on the ISS.

The space station really has been a unique experiment, an orbiting petri dish where humans have learned to work and live together in space. Wherever our spacefaring takes us in the future, it will owe a great deal to the legacy of the ISS. While we will lose the physical space station, Castaño-Rodriguez describes an infrastructural knowledge that will live on, at least in part, in where we take crewed space exploration next.

As part of her research, Castaño-Rodriguez has interviewed nearly a hundred astronauts, engineers and scientists involved in the ISS who have a unique insight into the importance of this orbiting science post. Perhaps the legacy of the ISS is best summed up by Sergei Krikalev, cosmonaut on the Expedition 1 mission 25 years ago.

"I asked him, when he was there on Expedition 1, did he remember any of the science experiments?" said Castaño-Rodriguez. "He looked me straight in the eye and said, 'the space station is the experiment.'"

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.