'Hubble tension' is back again as a new cosmic map deepens the puzzle

"It means cleaning house, narrowing the viable paths forward, and no longer spending energy on what are evidently dead ends."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

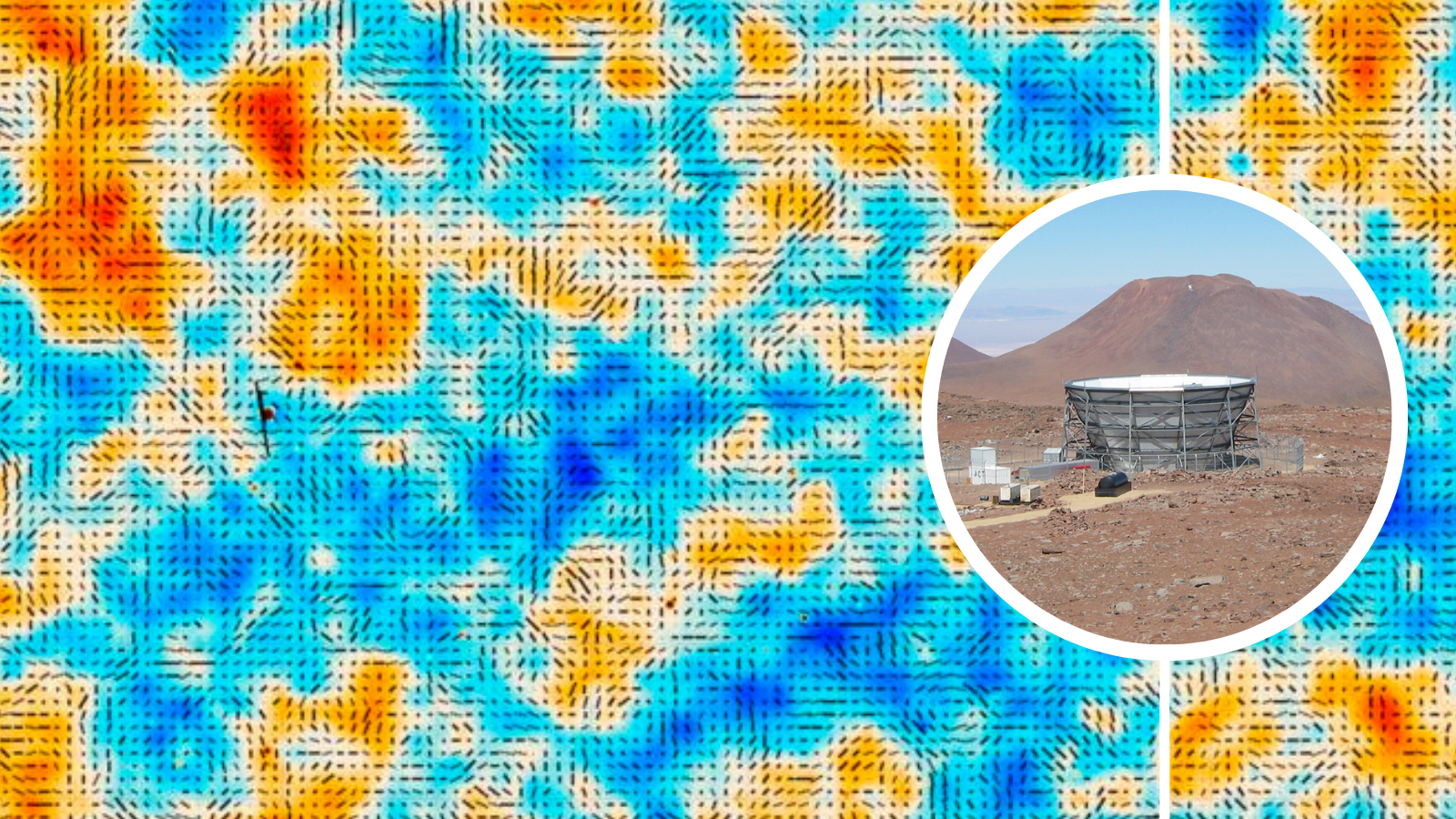

It may be curtains for the Atacama Cosmology Telescope (ACT), but the final data from its nearly 20 years of observations have laid out a roadmap for the future investigation of the cosmos. The data, in fact, represents a significant step forward in our understanding of the evolution of the universe — confirming a complex disparity in measurements of the "Hubble constant," the speed at which the very fabric of space is expanding.

In a nutshell, here's the disparity: When measured from the local universe using what are known as "Type 1a supernovas" as standardized distance buoys, the Hubble constant equals one number. But when measured from the distant cosmos using a "fossil light" as a measuring stick, it equals a different number. This has become known as the "Hubble tension."

The final data from ACT represent observations of the very distant cosmos, and they indeed confirm that the Hubble tension is a very real problem.

This may sound like it's a step backward for cosmology rather than a significant step forward, but by confirming that the value of the Hubble tension is different at different distances away from the Milky Way, ACT has helped rule out many "extended models" of the universe's evolution. These are alternative models to the so-called "standard model of cosmology," also known as the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (LCDM) model. That means that ACT, which began operations in 2007 and ended observations in 2022, leaves an important and fascinating legacy that will undoubtedly shape cosmology textbooks of the future.

ACT enabled this breakthrough by making precise measurements of the Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB), a cosmic fossil in the form of microwave light that fills the universe and is left over from an event that occurred just after the Big Bang. These CMB polarization maps complement the temperature maps of this fossil light collected by the European Space Agency (ESA) Planck spacecraft between 2009 and 2013. The difference between the two forms of CMB data is that the ACT polarization maps have far higher resolution.

"When we compare them, it’s a bit like cleaning your glasses," Erminia Calabrese, Cardiff University cosmologist and ACT collaboration member, said in a statement.

Planck's primary mission was to measure the temperature of the CMB, with scientists aiming to use this data to better understand tiny variations in the CMB, which could point to the composition of the early universe. However, this data collection left significant gaps, many of which have now been plugged by ACT.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It's the first time that a new experiment has reached the same level of observational capability as Planck," Thibaut Louis of the Université Paris-Saclay, France, said.

What is especially impressive about this feat is the fact that while Planck exploited its space-based location to investigate the CMB, ACT was based on Earth, albeit 16,400 feet (5,000 meters) above sea level in the dry atmosphere of northern Chile.

"Our new results demonstrate that the Hubble constant inferred from the ACT CMB data agrees with that from Planck — not only from the temperature data, but also from the polarization, making the Hubble discrepancy even more robust," Colin Hill, a cosmologist at Columbia University, said in the statement.

With this information at hand, cosmologists can make progress by accepting that something is missing from the LCDM model while simultaneously eliminating other models that suggest the Hubble constant is the same across the cosmos. In fact, researchers have already pitted this data against some of those main extended models, with a clear and decisive outcome.

"We assessed them completely independently," Calabrese said. We weren't trying to knock them down, only to study them. And the result is clear: The new observations, at new scales and in polarization, have virtually removed the scope for this kind of exercise. It does shrink the theoretical 'playground' a bit."

The team's research is available on the paper repository site arXiv, with two companion papers also published to the site.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.