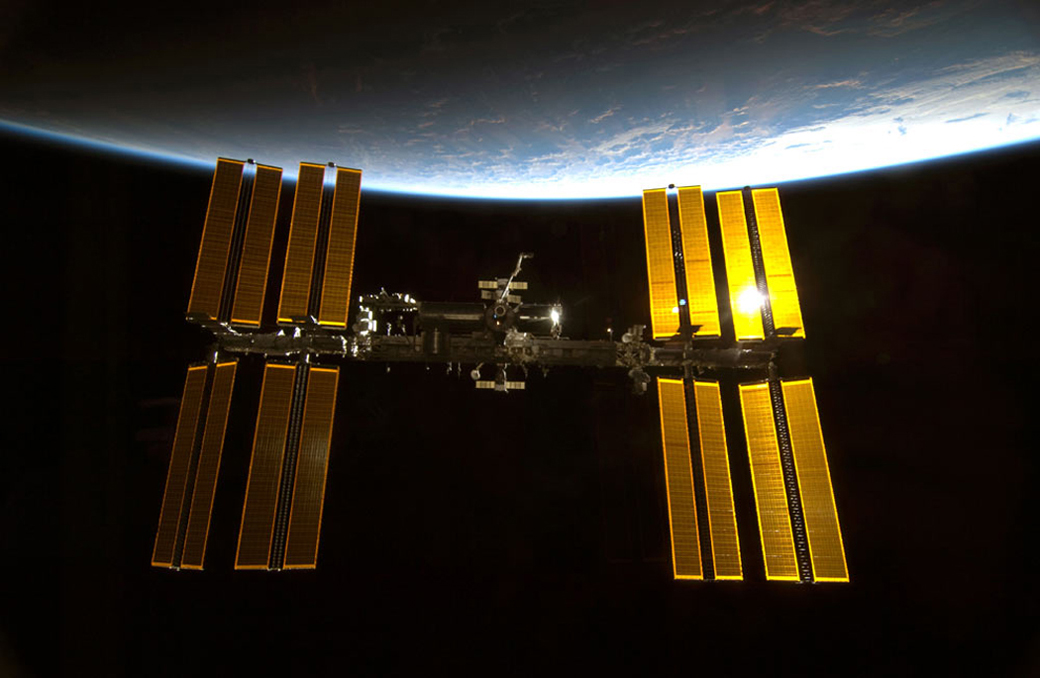

Russia Open to Extending Life of International Space Station to 2028

COLORADO SPRINGS, Colo. — Russia is ready to discuss extending the life of the International Space Station (ISS) to 2028, said Igor Komarov, director general of the Russian national space agency, Roscosmos.

Here at the 33rd annual Space Symposium yesterday (April 4), Komarov spoke about the need to maintain a research station in low Earth orbit if humans hope to eventually travel to Mars. He also discussed the agency's plans to send a new module to the space station in 2018, when the agency will also re-add a third crew member to the station.

In what he said was his first visit to the U.S. while serving in his current position, Komarov confirmed a proposal within the agency to build a new space station if the ISS is retired after 2024. Currently, the U.S. and Russia each manage and support half of the station, and other international collaborators contribute. Those countries have committed to financial support and maintenance of the station through 2024.

But Komarov also said Roscosmos is "ready to discuss" the possibility of extending the life of the station through 2028 with those international partners.

"I think we need to prolong our collaboration in low Earth orbit," Komarov said.

If the station were to be retired and no substitute were established, research taking place in low Earth orbit would take a significant hit. The loss of the station would more or less wipe out investigations into how the space environment affects the human body over long periods, which many space experts, including Komarov, agree is necessary if humans are to make the long journey to Mars.

Roscosmos has been working on an additional module for the space station, called the Multipurpose Laboratory Module (MLM), that the agency plans to launch in 2018, Komarov said. (A recent article in Popular Mechanics suggests there may be problems with the module, which was originally scheduled for launch in 2007 and again in 2013.) Once that module launches, Komarov said, the agency plans to raise the number of Russian cosmonauts on board the station from two to three; the agency recently reduced its crewmember count from three to two.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Roscosmos is also working on a science module and a docking module, Komarov said, and together, these three space rooms could form the core of an independent Russian station, SpaceNews reported in September of last year.

Komarov said the possibility of building a new station from the three modules is being discussed as a possible means of avoiding the loss of a laboratory in low Earth orbit if the ISS is retired in 2024.

"It doesn't mean we don't want to continue cooperation [with other countries]," he said. "We just want to be on the safe side. …. We want to prolong and continue our research in low Earth orbit."

Space station, moon, Mars

Russia, like the U.S., is interested in sending humans to Mars, Komarov said.

"Going to Mars is a great idea, and all nations and all agencies are interested [in it]," Komarov said. But he indicated that Russia is not just looking to plant its flag in Martian dust and return to Earth. Rather, the country seeks to establish a program that would support long-term human exploration of Mars. To accomplish that goal, Komarov emphasized the need for intermediary steps on the way to the Red Planet.

Developing a long-term human presence will require a practical, "step-by-step" program for reaching the Red Planet, Komarov said. Those steps include a human presence in low Earth orbit, then on the surface of the moon, then on Mars, and then to even more exotic or distant solar system destinations.

Many spaceflight experts have said that a consistent human presence in low Earth orbit provides a valuable training ground for astronauts who may go on to more distant destinations, including the moon or Mars. The space station provides a place for humans to develop the skills they'd need to survive in those locations, including growing fresh food, and exercising to prevent bone loss and muscle deterioration.

In 2015, Russia and the U.S. launched a joint mission to have two humans live on the station for a full year. NASA astronaut Scott Kelly and cosmonaut Mikhail Kornienko returned to Earth on March 1, 2016, and NASA is starting to release the results of scientific studies on how the trip affected Kelly's body and psyche. (Russian cosmonauts have lived in space for longer periods in the past, but those people were not subjected to the extensive amount of testing that was applied to the astronauts in the One-Year Mission.)

The space station is an essential part of humanity's journey to Mars, but Komarov also emphasized the importance of using the moon as another stepping stone on that journey.

Spaceflight experts have discussed extensively the idea that space agencies or private companies should send humans back to the moon before sending them to Mars, primarily to test and develop the technologies necessary for keeping astronauts safe and healthy.

"We shouldn't be eager to go very fast ahead and skip some stages that we have to do," Komarov said earlier in the day while speaking on a panel comprising 15 leaders of national space agencies. He added that the agency is currently planning a robotic mission to the moon that will include an orbiter and a lander. He did not offer more details about that mission.

NASA's Constellation Program, which then-President Barack Obama canceled in 2010 would have sent humans back to the moon or cislunar space. Much of that program was repurposed into the agency's current program to build the Orion human space capsule and the Space Launch System rocket, both of which will help get humans to Mars in the first half of the 2030s, NASA officials have said.

Challenges on the way to Mars

However, although NASA and private companies such as SpaceX and Boeing have made many exciting announcements about the prospect of sending humans to the Red Planet, the journey to Mars will require a very practical approach, Komarov said at the news conference.

"We need to understand that this is not an easy experiment," Komarov said. "There are a lot of issues that need to be solved by the people who are responsible.

"We want to bring people to Mars," he added. "They should be alive when they [reach] Mars. And … when we want to get them back, they should be safe and healthy. So we need to solve some medical problems. We should create a closed-loop system to support life. And we need to resolve the problem of radiation."

Indeed, space radiation is a serious threat to astronauts who want to venture out of the protective sheath of Earth's atmosphere and magnetic field. Experts have discussed various strategies for how to reduce the radiation dose that astronauts would receive, but it remains one of the key roadblocks to sending humans to Mars and bringing them back safely.

"We need to be ready for the next step … when we should go out of low Earth orbit, to the moon and to Mars," Komarov said.

Follow Calla Cofield @callacofield. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Calla Cofield joined Space.com's crew in October 2014. She enjoys writing about black holes, exploding stars, ripples in space-time, science in comic books, and all the mysteries of the cosmos. Prior to joining Space.com Calla worked as a freelance writer, with her work appearing in APS News, Symmetry magazine, Scientific American, Nature News, Physics World, and others. From 2010 to 2014 she was a producer for The Physics Central Podcast. Previously, Calla worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City (hands down the best office building ever) and SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California. Calla studied physics at the University of Massachusetts, Amherst and is originally from Sandy, Utah. In 2018, Calla left Space.com to join NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory media team where she oversees astronomy, physics, exoplanets and the Cold Atom Lab mission. She has been underground at three of the largest particle accelerators in the world and would really like to know what the heck dark matter is. Contact Calla via: E-Mail – Twitter