5 Human Body Questions the 1-Year Space Station Mission May Answer

NASA has a lot of questions about what happens to people who live in space for long periods of time, and it's almost time to get some answers.

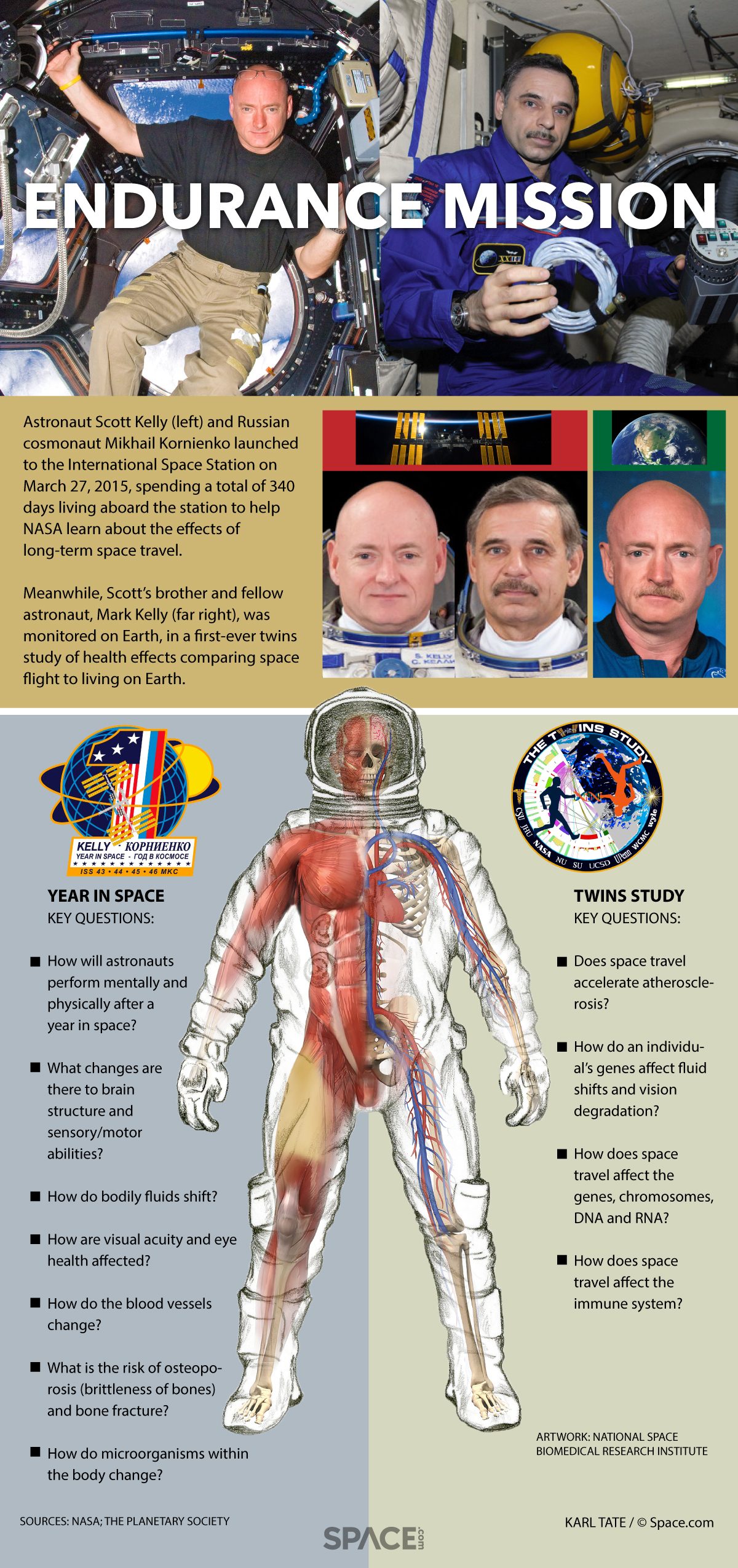

When NASA astronaut Scott Kelly and Russia's Mikhail Kornienko fly up to the International Space Station Friday (March 27) for a yearlong stay on the orbiting outpost, space agency scientists will get to work on experiments that could help get people to Mars one day.

Officials have a lot of information about what happens to a body in weightlessness for six months, but the 12-month space mission will mark the first time researchers can gather data about what happens to people in space for longer periods of time. It takes more than one year to get to Mars using currently understood propulsion methods, so learning more about the ways long spaceflight affects humans is key to one of NASA's main future goals: getting people to the Red Planet. [1-Year Space Station Mission Explained (Infographic)]

Here are five of the major questions NASA scientists are trying to answer with Kelly and Kornienko's yearlong space mission:

What happens to an astronaut's eyes after a year in space?

NASA scientists have long known that the shape of an astronaut's eye can change when in orbit for six months, but researchers aren't sure what will happen to a crewmember's eyes after a full year on the space station. Fluid in the body shifts when in microgravity for extended periods of time, sometimes affecting eyesight due to intracranial pressure. NASA hopes to use specialized experiments to learn more about what a long-term spaceflight can do to an astronaut's eyes.

Does an astronaut's immune system change?

NASA will monitor Kelly's immune system to see how a one year in space taxes his body. Scientists worry that long-term spaceflight could put astronauts at higher risk for atherosclerosis, a disease where plaque builds up in arteries.

"Spaceflight results in many negative health effects, and the causes may include microgravity, radiation, or isolation and stress," NASA immunologist Brian Crucian said in a video. "The immune system can be negatively affected by many of the factors associated with flight. Microgravity itself may directly inhibit immune cell function."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

How does an astronaut's stomach bacteria change?

Kelly's twin brother and fellow astronaut, Mark Kelly, will help scientists on the ground with experiments involving Scott's year in space. Scientists will monitor the stomach bacteria in both brothers to see how it might change while on the space station.

"Identical twins provide unique advantages," Northwestern University's Martha Vitaterna, a scientist involved with the research, said in a statement. "We can directly compare the space twin with the Earth twin because they are a genetic match."

How does a long spaceflight affect someone's mental health?

Some of the experiments Kelly and Kornienko will conduct won't have anything to do with needles or invasive experiments. Kelly is planning on keeping a journal of his time in space that he will share with officials on the ground, to give scientists some insight into his mental health during the long spaceflight. Researchers will also monitor how the crewmembers perform their tasks while fatigued.

What kind of exercise does an astronaut need?

NASA has designed a specific workout program geared toward keeping people fit in space. Microgravity can cause muscles to atrophy and contributes to bone loss, according to NASA. The space agency will be trying out a new workout plan during the one-year mission. The new plan could cut workout time down from the two hours astronauts currently spend doing physical activity on the station during their six-month trips.

"Two studies will evaluate a new exercise regimen and monitoring technology geared to protect our bones and muscles and measure changes in the hip region — this area is more susceptible to bone loss," John Charles of NASA's Human Research Program said in a video. "Preflight and postflight muscle performance will be measured using various technologies such as MRI scans and ultrasounds."

Read more about these experiments directly through NASA: http://www.nasa.gov/content/one-year-mission/

Visit Space.com on Friday for complete coverage of Kelly and Kornienko's launch on their one-year space mission.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebookand Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.