Supermoon Forecast: The Moon Hasn't Been This Close in Almost 69 Years

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

On Monday (Nov. 14) at 6:15 a.m. EST, the moon will arrive at its closest point to the Earth in 2016: a distance of 221,524 miles (356,508 kilometers) away. This distance, which is measured from the center of the Earth to the center of the moon, is within 85 miles (137 km) of the moon's closest possible approach to Earth; to be sure, this is an extreme perigee.

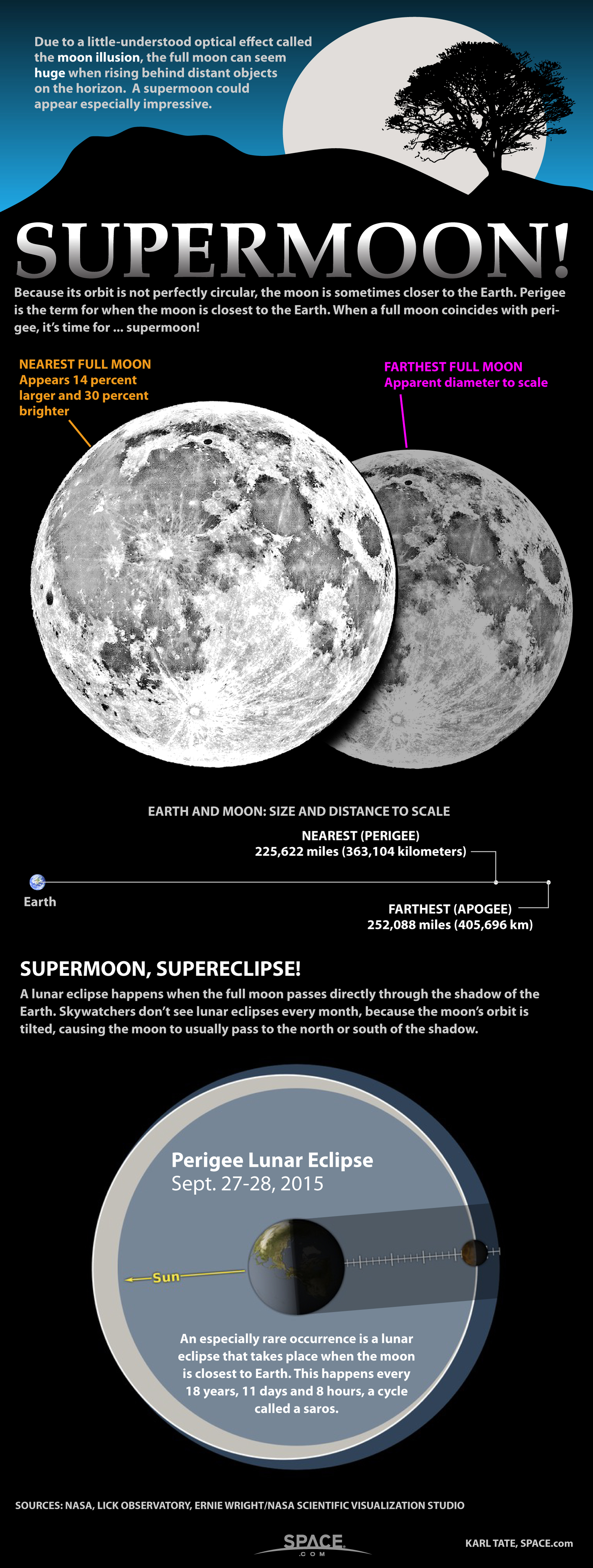

Two hours and 37 minutes after perigee (the moon's closest point to Earth), the orb will officially turn full. In recent years, the media has branded full moons that coincide with perigee as "supermoons," and this month's full moon will likely get a lot of extra attention since it will be the closest since Jan. 26, 1948. [Supermoon November 2016: When, Where & How to See It]

The Slooh Community Observatory will offer a live broadcast for November's full moon on Nov. 13 at 8 p.m. EST (0100 GMT on Nov. 14). You can also watch the supermoon live on Space.com, courtesy of Slooh.

So be prepared. It is certain that there will be considerable ballyhoo over this particular full moon. (I wonder if there will be somebody who will dare call this a "Super-duper-moon?")

The full moon won't approach this close again until November 2034, although there were even closer full moons in January 1912 and January 1930.

Is it really so super?

When the moon appears near to the horizon when it is rising (just before 5 p.m. on Nov. 14), the famous "moon illusion" will kick in, which makes our natural satellite appear exceptionally large. However, that illusion happens frequently when the full moon skims the horizon. The supermoon that shines down on us later on Nov. 14 really won't look that different from other full moons.

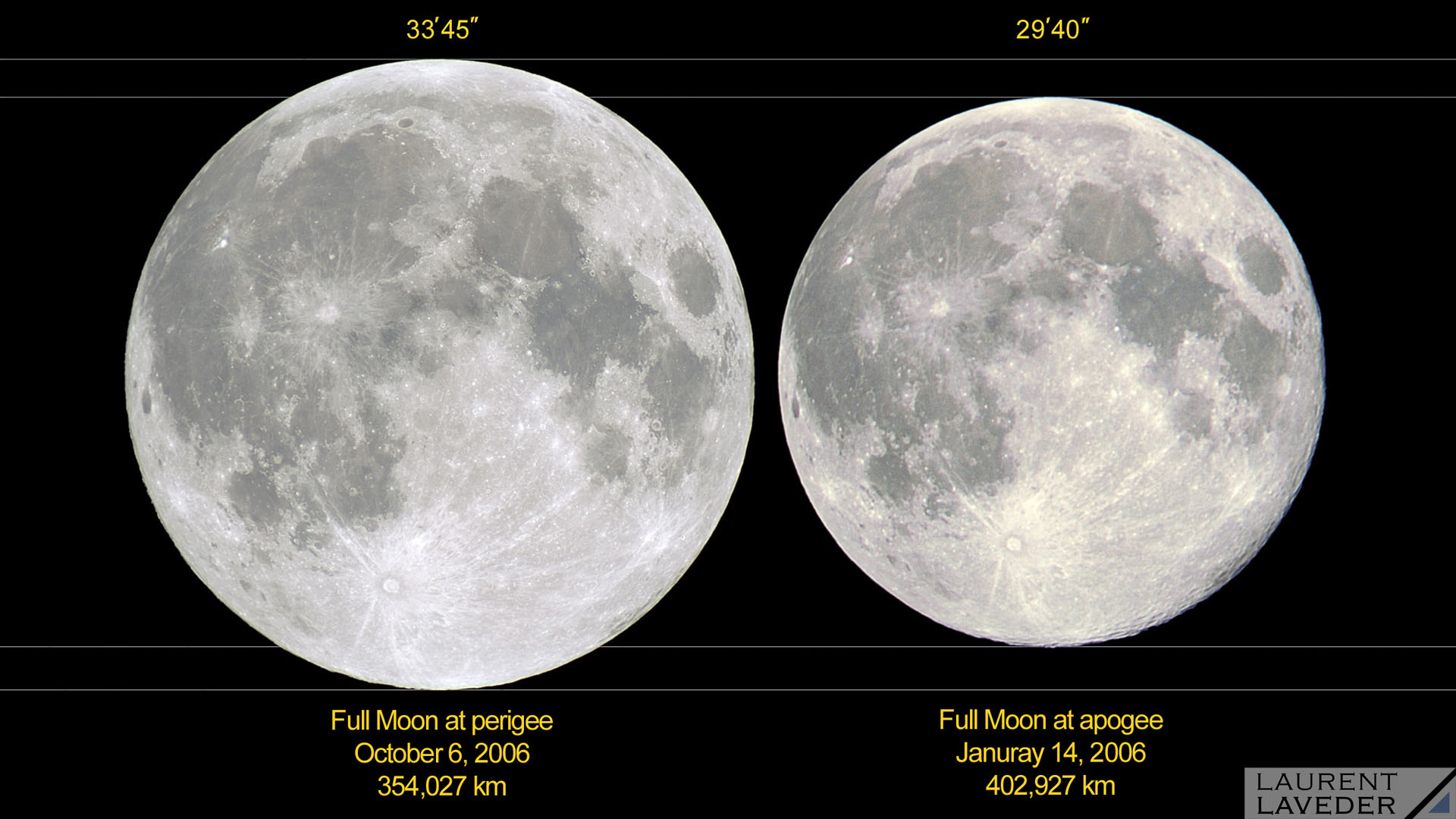

Yes, we will certainly hear through the mainstream media that on the night of Nov. 14 the moon will appear 14 percent larger and 30 percent brighter than to when it's at apogee (its farthest point from Earth), but such differences are actually quite subtle. No doubt many will be running outside all through that night, breathlessly trying to get a glimpse of what they will perceive as some sort of astonishing sight. And yet, honestly, if you were not aware of the circumstances regarding the moon's distance I would venture to guess that you wouldn't notice anything unusual at all.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

One well-known astronomer takes a very dim view of the term supermoon. Neil deGrasse Tyson, director of New York's Hayden Planetarium, thinks the term is highly overblown. "There is something called a supermoon," Tyson has noted, adding, "I don't know who first called it a supermoon. I don't know, but if you have a 16-inch pizza, would you call that a super pizza compared with a 15-inch pizza?"

It's not even a full moon

A full moon theoretically lasts just a moment, and that moment is imperceptible to ordinary observation. For a day or so before and after most will speak of seeing the nearly full moon as "full": the shaded strip is so narrow, and changing in apparent width so slowly, that it is hard for the naked eye to tell, at least in a casual glance, whether it's present or on which side it appears. This is important to know, since when folks are looking skyward at the "full" moon on Nov. 14, it really won't be full at all.

Remember?

At the beginning of this column, I pointed out that the moon will turn full at 8:52 a.m. EST on Nov. 14. If you live in the western half of the United States or Canada, you'll be able to see the moon at full phase just before it sets that morning. But elsewhere it turns full after it has set. So when you look at the moon later that night, it will, in the strictest sense, not be a full, but a gibbous moon — 99, rather than 100, percent illuminated and waning (reducing in illumination). [Supermoon Secrets: 7 Surprising Big Moon Facts]

Dramatic tides

The near coincidence of this month's full moon with perigee will result in a dramatically large range of high and low ocean tides: an unusually lower-than-normal low tide, followed about 6 hours later by an unusually higher-than-normal high tide. In the latter case, any coastal storm at sea around this time will almost certainly aggravate coastal flooding problems.

Such an extreme tide is known as a perigean spring tide, where the word "spring" is derived from the German springen, "to spring up," and is not a reference to the spring season.

Actually, every month, "spring tides" occur when the moon is full and new. At these times the moon and sun form a line with the Earth, so their tidal effects add together. (The sun exerts a little less than half the tidal force of the moon.) "Neap tides," on the other hand, occur when the moon is at first and last quarter and works at cross-purposes with the sun. At these times tides are weak.

Tidal forces vary as the inverse cube of an object's distance. This month the moon is 14 percent closer at perigee than at apogee, and so it exerts 48 percent more tidal force during the spring tides of Nov. 14 than during the spring tides near apogee two weeks before and after.

Some final thoughts

While this will indeed be the "biggest full moon of 2016," the variation of the moon's distance is not readily apparent to observers viewing the moon directly. However, its movement may be seen in the tides — those folks who are positioned at Burntcoat Head, on the "Noel Shore" along the south side of the Minas Basin, near the Bay of Fundy in eastern Canada, for instance, always know when the moon is near when the height of the water begins to rise. The increase in the vertical tidal range of 10 to as much as 20 feet (3 to 6 meters) automatically signals when the moon lies near perigee, whether the moon is actually in view or not.

Conversely, at low tide, water levels can end up being exceptionally low. I guess people living along the shore near the Bay of Fundy might then say: "Long tide, no sea."

Editor's note: If you snap an awesome photo of the moon that you'd like to share with Space.com and our news partners for a potential story or gallery, send images and comments to managing editor Tariq Malik at spacephotos@space.com.

Joe Rao serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, the Farmer's Almanac and other publications, and he is also an on-camera meteorologist for News 12 Westchester, N.Y. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Joe Rao is Space.com's skywatching columnist, as well as a veteran meteorologist and eclipse chaser who also serves as an instructor and guest lecturer at New York's Hayden Planetarium. He writes about astronomy for Natural History magazine, Sky & Telescope and other publications. Joe is an 8-time Emmy-nominated meteorologist who served the Putnam Valley region of New York for over 21 years. You can find him on Twitter and YouTube tracking lunar and solar eclipses, meteor showers and more. To find out Joe's latest project, visit him on Twitter.