Do you suffer from IBS? This doctor says 'gravity intolerance' may be to blame

One doctor argues that to be healthier, we need to be better at managing our bodies' interactions with gravity.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Gravity, one of the four fundamental forces of nature, keeps us down to Earth (literally), but our body's relationship to it could explain our susceptibility to some common health conditions — for instance, irritable bowel syndrome.

At least, that's what Dr. Brennan Spiegel, director of health services research at Cedars-Sinai, proposes in his new book, "Pull: How Gravity Shapes Your Body, Steadies the Mind, and Guides Our Health." Spiegel, also a gastroenterologist at Cedars-Sinai and the University of California, Los Angeles, got the idea that disease could be directly connected to the gravitational force when considering commonalities among patients with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which affects up to 10% of the world's population.

For example, people with IBS are more likely to have anxiety and depression and experience pain sensitivity conditions such as fibromyalgia. People with IBS also have higher rates of a condition called postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome (POTS), which causes dizziness and other symptoms when a person moves from seated to standing positions. On their face, none of these comorbidities have a clear line connecting them to each other, or even to IBS. But zoom the lens way out, and there could be one unifying force behind them, Spiegel argues. "When you start looking at all these things, they all have one thing in common," he said. "And that's gravity intolerance."

Article continues belowHis hypothesis of what it means to be "gravity intolerant" is outlined in his original article introducing the theory, published in The American Journal of Gastroenterology in 2022. In it, Spiegel explains IBS susceptibility through what he calls a "G-force cube" (with the G-force referencing the gravitational force) of factors that tip the scale on whether we develop symptoms. These include resistance, or the structure of the intestines and how they stand up to gravity, detection, or the perception of the body's strain against gravity, and vigilance, or the body's ability to monitor for gravity-altering events.

Still, especially because this theory is preliminary and requires more research, Spiegel wants it to be known that the hypothesis is "not a replacement model" for risk factors research has already identified for IBS, including bacterial overgrowth in the intestines, inflammation, diet and genetic predisposition, just to name a few. Instead, he sees gravity's potential role in the development of the condition as a "unifying lens" to consider it through.

"The gravity model doesn't displace those factors," Spiegel said. "It helps organize them."

Related: Microgravity in space can alter human cells. We now know how.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

What's your 'gravitype'?

According to Spiegel, we're all susceptible to the gravitational force that exerts itself in our guts. He cited the "falling" sensation of butterflies in your stomach when you're anxious or falling in love, or the terrifying thrill of falling down a roller coaster, as examples of how gravity alerts us to danger (rightly or wrongly) by acting as "an ignition in our belly."

"It's almost like we have a G-force accelerometer in our gut that tells us, 'You're at risk,'" Spiegel explained.

Spiegel argues that a person's susceptibility to developing IBS could come down to the three aforementioned pieces of the G-force cube: gravity-related features: g-force resistance, g-force detection and G-force vigilance.

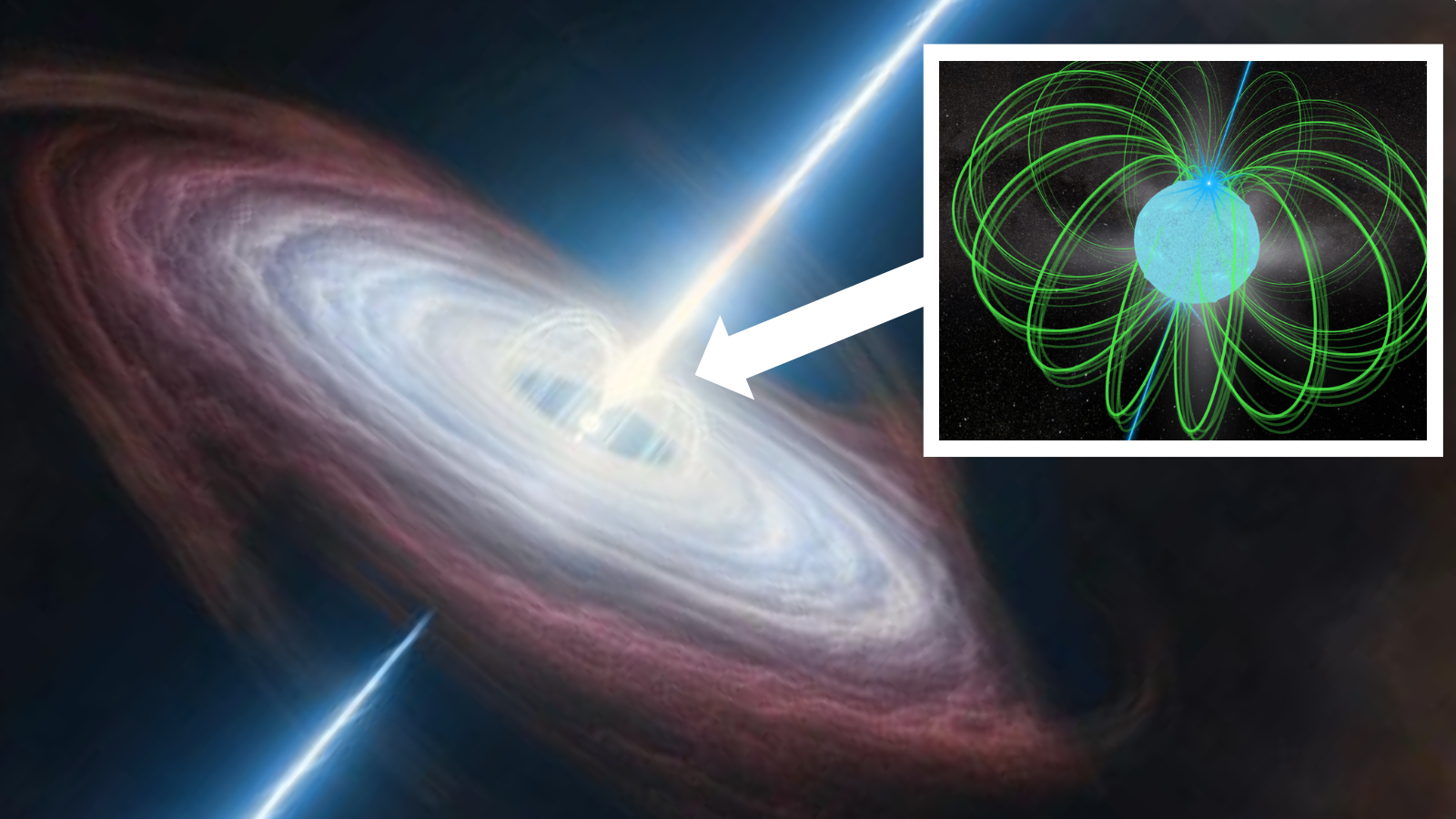

G-force resistance refers to the way our intestines are arranged in our body and how they function by pushing and flowing within the context of Earth's gravity. To illustrate how problems may occur when the relationship between a person's digestive system and gravity is disrupted, Spiegel pointed to past space research on why astronauts tend to experience more digestive problems — like heartburn, diarrhea and constipation — in low gravity.

The structure of our intestines may be one reason why regular exercise and yoga have been shown to alleviate IBS symptoms and regulate bowel movements, Spiegel said. By strengthening your abdominal wall and musculoskeletal system, you are leveraging yourself against gravity.

"There's a suspension system inside the belly that literally holds this sack of potatoes that you've got dangling down in your belly," Spiegel explained. How we're able to balance and hold that sack of dangling potatoes matters, and it also gets more difficult with natural age-related changes to muscle and bone health.

Gut-brain connection

Another factor in the link between IBS and gravity relates to the gut-brain connection. G-force detection refers to how our peripheral nervous system detects shifts in gravity, and g-force vigilance relates to how our central nervous system responds to these changes through different symptoms or sensations.

Some people (not just those with IBS) are sensitive to gravitational shifts, while others are barely fazed by them. (Spiegel pointed to Alex Honnold, who made history by free-climbing El Capitan in Yosemite National Park and recently gained popularity for his skyscraper free climb that streamed live on Netflix), as an example of someone who appears to be less frightened by gravity-related risks.

As a fun exercise to gauge your susceptibility to gravity, or "gravitype," Spiegel created a quiz that rates how physically durable you are against gravity, how easily your nervous system perceives shifts in gravity (or universal forces at large), and how emotionally resilient you are to life's ups and downs.

A growing body of research shows the connection between the gut microbiome — the community of bacteria, fungi and other microbes living in the gut — and many aspects of overall health and well-being, including mental health. What's more, researchers discovered that astronauts' gut microbiomes were negatively affected by microgravity.

Spiegel pointed to the neurotransmitter serotonin, which regulates mood and has other crucial functions. About 90% of the body's serotonin is found in the gastrointestinal tract, which points back to the gut-brain axis. A study published this summer in the journal Experimental and Molecular Medicine examined what's known about the gut microbiome and how it's linked to astronauts' mental health in space, as well as evaluated where research is lacking. The study authors proposed routine gut microbiome testing of space travelers "as a noninvasive tool for early detection of neuropsychological risks in astronauts."

"Serotonin being elevating isn't just metaphorical," Spiegel said. "If [we] didn't have it, you and I would be collapsed on the floor like flaccid sacks."

Like so many other aspects of human health, future space studies on how gravity directly affects human health will not only aid astronauts but also help clinicians on Earth incorporate the fundamental forces of our universe to improve people's well-being.

The case for sky-high theories in medicine

It's important to remember that Spiegel's 2022 hypothesis on IBS and gravity, and his book expanding it to more aspects of our health, is just that: a hypothesis. It doesn't negate the reality of IBS, or rule out the need to test for other conditions with overlapping symptoms. Instead, it asks the question about how gravity may influence our health, which matters more each year as humans continue to enthusiastically expand into space and take their Earthborne bodies, and Earthborne health problems, with them.

It's worth considering how we are creatures of our environment, and it usually doesn't hurt to broaden the scope when considering how our environment — in space and on Earth — impacts our health.

"The way I like to think about it is: Gravity was here long before we were, and it will be here long after we're gone," Spiegel said, "so it stands to reason that every part of our body — every tendon, every organ, every nerve — evolved in large part to manage this fundamental force."

Jessica Rendall is a reporter based in Brooklyn with a special interest in what keeps humans healthy — both on Earth and in space. Previously, she was a staff wellness writer at CNET and a freelancer who covered public health, music and lifestyle. She studied journalism at the University of Missouri and enjoys watching movies with subtitles on.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.