Alien Life Could Be Hiding Out on Far Fewer Planets Than We Thought

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Where is complex alien life hanging out in the universe? Likely not on planets stewing in toxic gases, according to a new study that dramatically reduces the number of worlds where scientists will have the best luck finding ET.

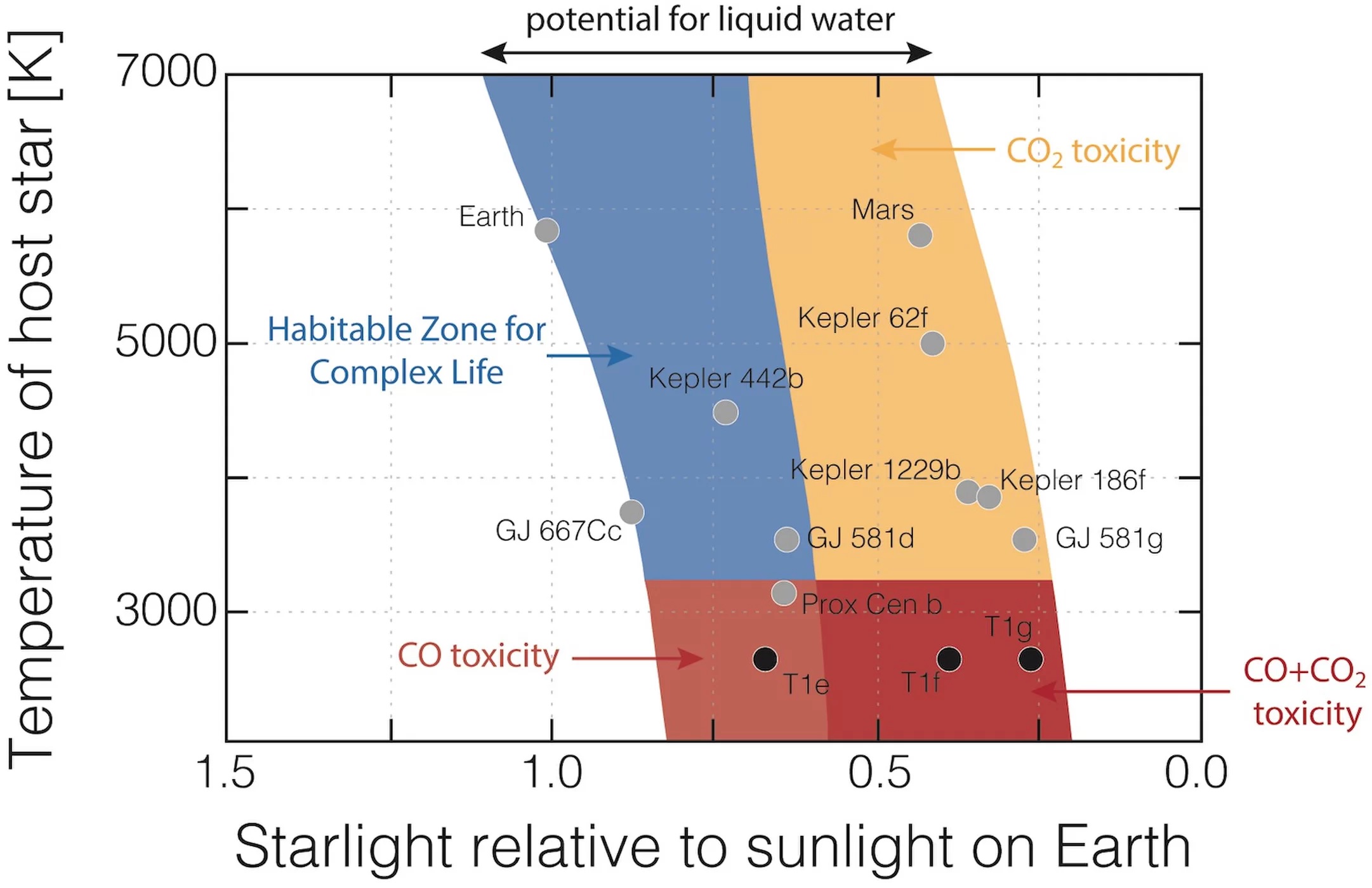

In the past, researchers defined the "habitable zone" based on the distance between the planet and its star; planets that, like Earth, orbit at just the right distance to accommodate temperatures in which liquid water could exist on the planetary surface would be considered "habitable." But while this definition works for basic, single-celled microbes, it doesn't work for complex creatures, such as animals ranging from sponges to humans, the researchers said.

When these extra parameters — needed for complex creatures to exist — are taken into account, this habitable zone shrinks substantially, the researchers said. For instance, planets with high levels of toxic gases, such as carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide, would drop off the master list. [9 Strange, Scientific Excuses for Why Humans Haven't Found Aliens Yet]

"This is the first time the physiological limits of life on Earth have been considered to predict the distribution of complex life elsewhere in the universe," study co-researcher Timothy Lyons, a distinguished professor of biogeochemistry and director of the Alternative Earths Astrobiology Center at the University of California, Riverside (UCR), said in a statement.

To investigate, Lyons and his colleagues created a computer model of the atmospheric climate and photochemistry (a field that analyzes how different chemicals behave under visible or ultraviolet light) on a range of planets. The researchers began by looking at predicted levels of carbon dioxide, a gas that's deadly at high levels but is also needed to keep temperatures above freezing (thanks to the greenhouse effect) on planets that orbit far from their host stars.

"To sustain liquid water at the outer edge of the conventional habitable zone, a planet would need tens of thousands of times more carbon dioxide than Earth has today," study lead researcher Edward Schwieterman, a NASA postdoctoral fellow working with Lyons, said in the statement. "That's far beyond the levels known to be toxic to human and animal life on Earth."

Once carbon dioxide toxicity is factored into the equation, the traditional habitable zone for simple animal life is sliced in two, the researchers said. For complex life like humans, which is more sensitive to high levels of carbon dioxide, this safe zone shrinks to less than a third of the traditional area, the researchers found.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Under the new parameters, some stars have no safe-for-life zone; that includes Proxima Centauri and TRAPPIST-1, two of the sun's closest neighbors. That's because planets around these suns likely have high concentrations of carbon monoxide, the researchers said. Carbon monoxide can bind to hemoglobin in animal blood, and even small amounts of it can be deadly. (Conversely, another recent study argued that carbon monoxide might be a sign of extraterrestrial life, but as Schwieterman put it, "these [planets] would certainly not be good places for human or animal life as we know it on Earth.")

The new guidelines may help researchers trim the number of planets where signs of alien life look promising, a boon to the field, given that there are almost 4,000 confirmed planets out there that orbit stars other than the sun.

"Our discoveries provide one way to decide which of these myriad planets we should observe in more detail," study co-researcher Christopher Reinhard, a former UCR graduate student who is now an assistant professor of Earth and atmospheric sciences at the Georgia Institute of Technology, said in the statement. "We could identify otherwise-habitable planets with carbon dioxide or carbon monoxide levels that are likely too high to support complex life."

The study was published online today (June 10) in The Astrophysical Journal.

- Greetings, Earthlings! 8 Ways Aliens Could Contact Us

- 7 Huge Misconceptions About Aliens

- 4 Places Where Alien Life May Lurk in the Solar System

Originally published on Live Science.

Laura is an editor at Live Science. She edits Life's Little Mysteries and reports on general science, including archaeology and animals. Her work has appeared in The New York Times, Scholastic, Popular Science and Spectrum, a site on autism research. She has won multiple awards from the Society of Professional Journalists and the Washington Newspaper Publishers Association for her reporting at a weekly newspaper near Seattle. Laura holds a bachelor's degree in English literature and psychology from Washington University in St. Louis and an advanced certificate in science writing from NYU.