What are 'dark' stars? Scientists think they could explain 3 big mysteries in the universe

"This is a structure we've never seen before, so it could be a new class of dark object."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

"Dark stars" could help solve three seemingly disconnected mysteries that emerged at cosmic dawn — mysteries recently discovered by the James Webb Space Telescope. The puzzles include the surprising overabundance of supermassive black holes in the early universe, the unexpected existence of "blue monster" galaxies, and the so-called "little red dots" scientists have been finding. The latter is an entirely new class of cosmic objects in the early universe that appear to have disappeared before the cosmos was around 2 billion years old.

Dark stars are hypothetical objects that are proposed to have existed in the early universe. Rather than being powered by nuclear fusion, as normal stars are, dark stars are thought to have been powered by the annihilation of dark matter particles. "Dark" refers to that source of these stars' energy; they would have, in fact, been incredibly bright.

"Some of the most significant mysteries posed by the [James Webb Space Telescope's] cosmic dawn data are in fact features of the dark star theory," research leader Cosmin Ilie of Colgate University said in a statement.

Article continues belowIf dark stars existed, they would have been capable of forming in the universe before ordinary stars could have formed. When ultradense cores of dark matter are exhausted, it is theorized that dark stars could collapse to form the massive "seeds" for supermassive black holes.

These seeds would be much more massive than the black holes formed when even the most massive stars run out of fuel for nuclear fusion. This, coupled with the fact that dark stars could have existed before normal stars, would allow supermassive black holes to form much faster than the standard chain of black hole mergers thought to create supermassive black holes.

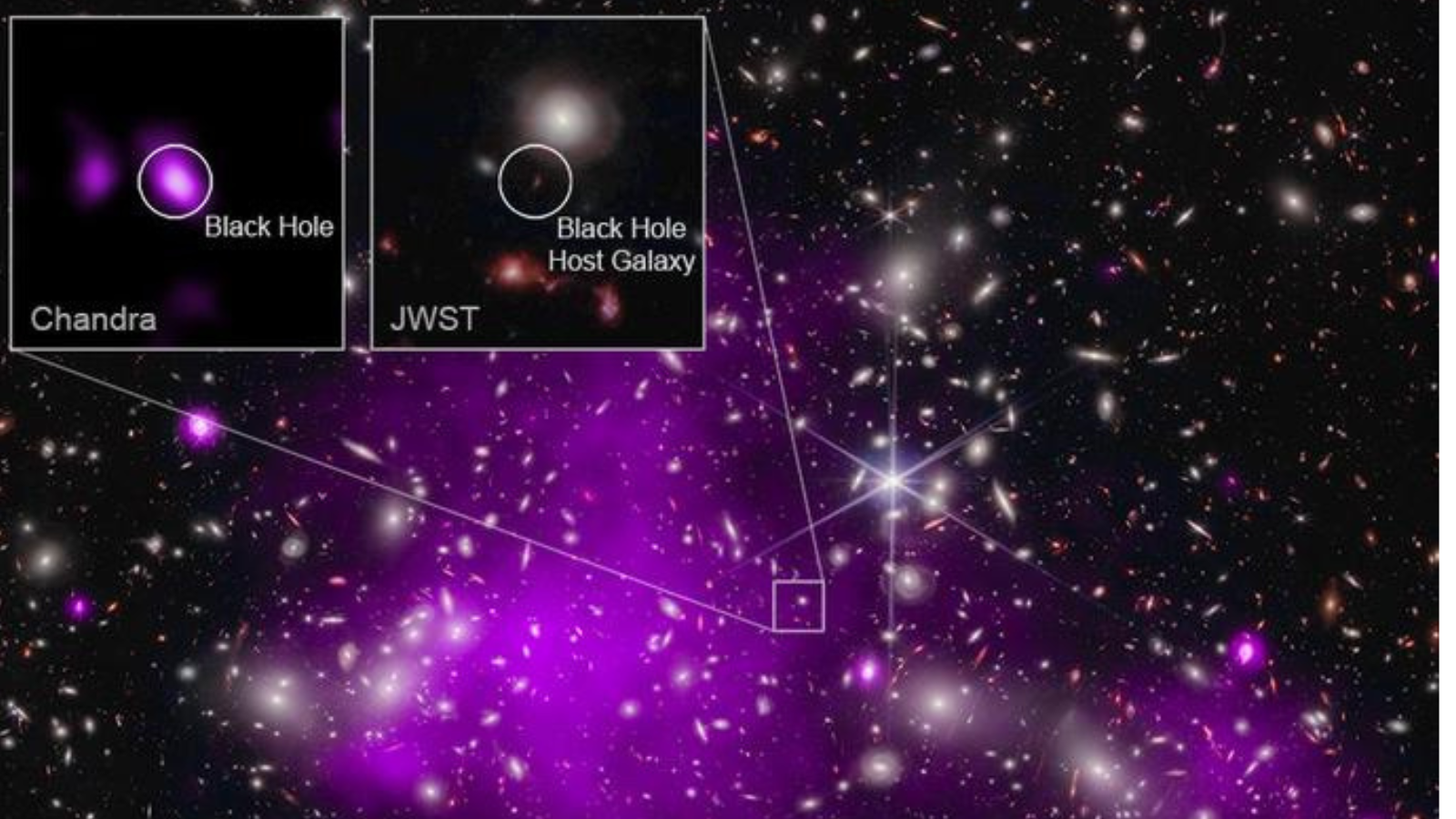

That could explain how the JWST has been able to detect a large population of supermassive black holes in the universe less than 1 billion years after the Big Bang.

Those black holes aren't the only unexpected things the JWST has been detecting in the early universe since it began observations in 2022. The $10 billion space telescope has also been spotting extremely bright, ultra-compact and incredibly dense galaxies that lack an abundance of dust. Categorized as "blue monsters," these are galaxies that no cosmological simulation or model of the formation of the earliest galaxies had predicted the existence of prior to the era of the JWST.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team suggests these blue monsters aren't galaxies at all, but are instead incredibly luminous dark stars that, because of their brightness, are being mistaken for entire galaxies with populations of stars packed into a region no wider than a few hundred light-years.

Little red dots, though much dimmer than blue monsters, are also notable for how compact they are, requiring an almost impossibly dense packing of stars, if they are indeed galaxies. The other puzzling characteristic of little red dots is they emit weakly in ultraviolet light and don't seem to emit X-rays at all.

This team argues the collapse of dark stars that have exhausted their dark matter could result in black holes that are still surrounded by layers of stellar material and that could have the effect of semi-obscuring ultraviolet light and completely obscuring X-ray emissions in a way that the dust haloes of galaxies alone cannot.

For now, dark stars remain purely hypothetical, though some observational evidence is beginning to emerge. Nevertheless, this research represents an intriguing attempt to solve three cosmological puzzles with one mechanism.

"Supermassive dark stars can offer a solution to several pressing puzzles in astronomy and astrophysics, as discussed in depth in this paper," the authors concluded. "To our knowledge, there is no other mechanism that can achieve this simultaneously."

The results are in a paper published in December 2025 in the journal Astrophysics and Cosmology at High Z.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.