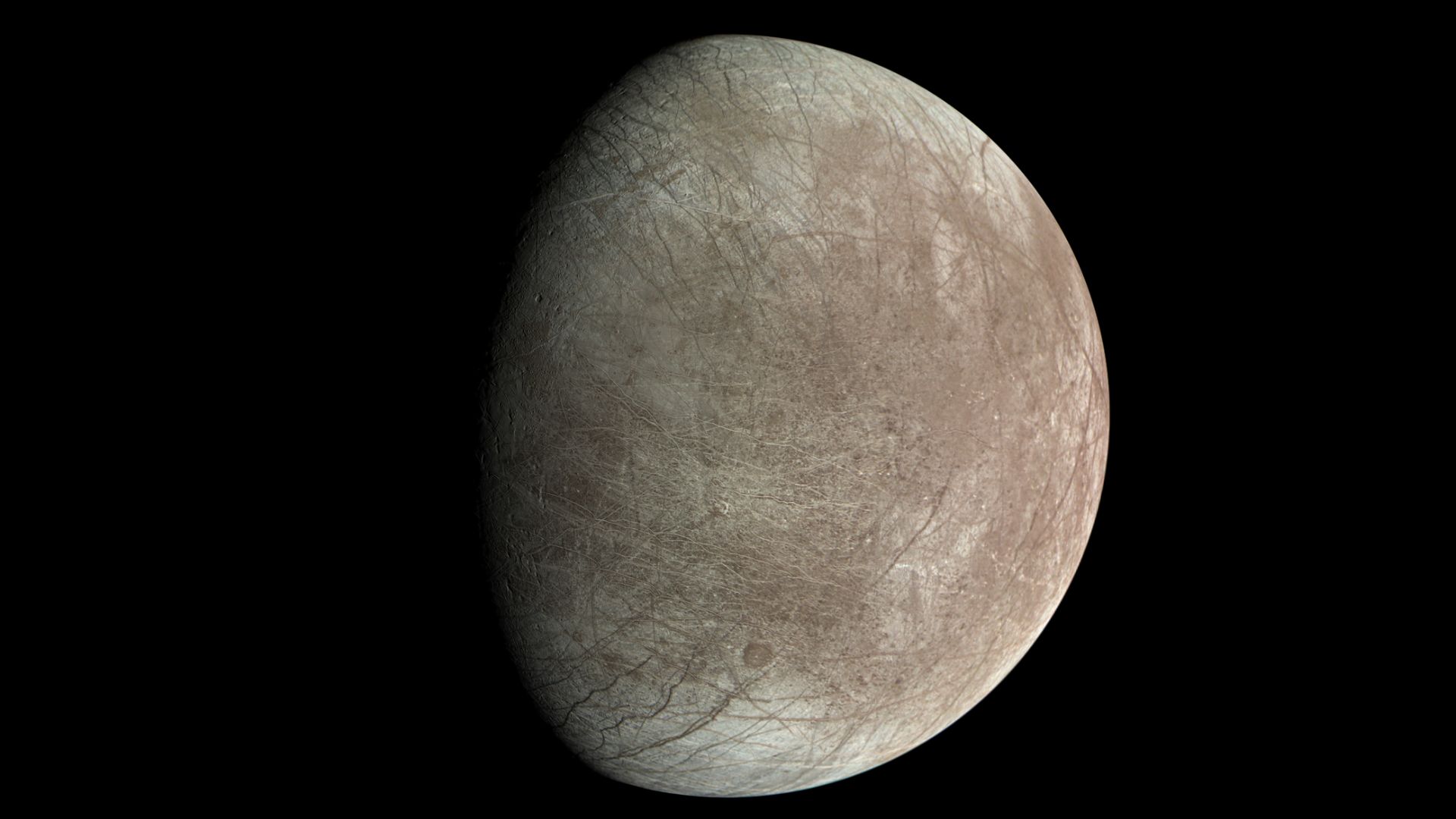

Jupiter's moon Europa has an ice shell about 18 miles thick — and that could be bad news for alien life

A thick shell "implies a longer route that oxygen and nutrients would have to travel to connect Europa’s surface with its subsurface ocean."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

After years of debate, NASA researchers have zeroed in on the thickness of the Europa's ice shell.

We first discovered that the Jupiter moon's surface looked icy in 1979, when Voyager 2 flew by. Another NASA mission, the Galileo Jupiter orbiter, later confirmed the ice shell while it inspected the giant planet, Europa, and other Jovian moons during the 1990s.

Since then, scientists have been in two camps, championing conflicting theories on the thickness of Europa's ice shell. One theory holds that the shell — which is thought to hide a huge, buried ocean of liquid water — is less than 1 mile (1.6 kilometers) thick, while the other posits that it spans tens of miles.

Now, we appear to have an answer. Using data the Juno Jupiter orbiter gathered in 2022 using its Microwave Radiometer instrument, researchers at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) in Southern California calculate that the shell is about 18 miles (28.9 km) thick.

"The 18-mile estimate relates to the cold, rigid, conductive outer layer of a pure water ice shell," Steve Levin, Juno project scientist and co-investigator from JPL, said in a NASA statement on Tuesday (Jan. 27).

"If an inner, slightly warmer convective layer also exists, which is possible, the total ice shell thickness would be even greater," Levin continued. "If the ice shell contains a modest amount of dissolved salt, as suggested by some models, then our estimate of the shell thickness would be reduced by about 3 miles [5 km]."

Understanding the makeup and structure of Europa's icy surface is important, because NASA researchers — and many other scientists around the world — want to find out if the moon hosts alien life. Previous research suggests that the ingredients for life could exist in the moon's subsurface ocean.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"How thick the ice shell is and the existence of cracks or pores within the ice shell are part of the complex puzzle for understanding Europa's potential habitability," Scott Bolton, Juno principal investigator from the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, said in the NASA statement.

And a thick ice shell might not be great news for Europa's life-hosting potential. This feature "implies a longer route that oxygen and nutrients would have to travel to connect Europa’s surface with its subsurface ocean," NASA officials wrote in the statement.

This new insight into Europa will provide helpful context for the two spacecraft that are en route to the Jovian system right now. NASA's Europa Clipper should arrive in orbit around Jupiter to investigate Europa's habitability in 2030, and the European Space Agency's Juice (JUpiter ICy moons Explorer) will get there a year later.

The new Europa results were published Dec. 17 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Julian Dossett is a freelance writer living in Santa Fe, New Mexico. He primarily covers the rocket industry and space exploration and, in addition to science writing, contributes travel stories to New Mexico Magazine. In 2022 and 2024, his travel writing earned IRMA Awards. Previously, he worked as a staff writer at CNET. He graduated from Texas State University in San Marcos in 2011 with a B.A. in philosophy. He owns a large collection of sci-fi pulp magazines from the 1960s.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.