Did a titanic moon crash create Saturn's iconic rings?

Debris from the collision could have formed another moon of Saturn called Hyperion, and affected the tilt of Saturn itself.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Saturn's largest moon, the smog-enshrouded Titan, could be the result of a dramatic merger between two other moons that initiated a cavalcade of effects — including the formation of Saturn's beautiful rings.

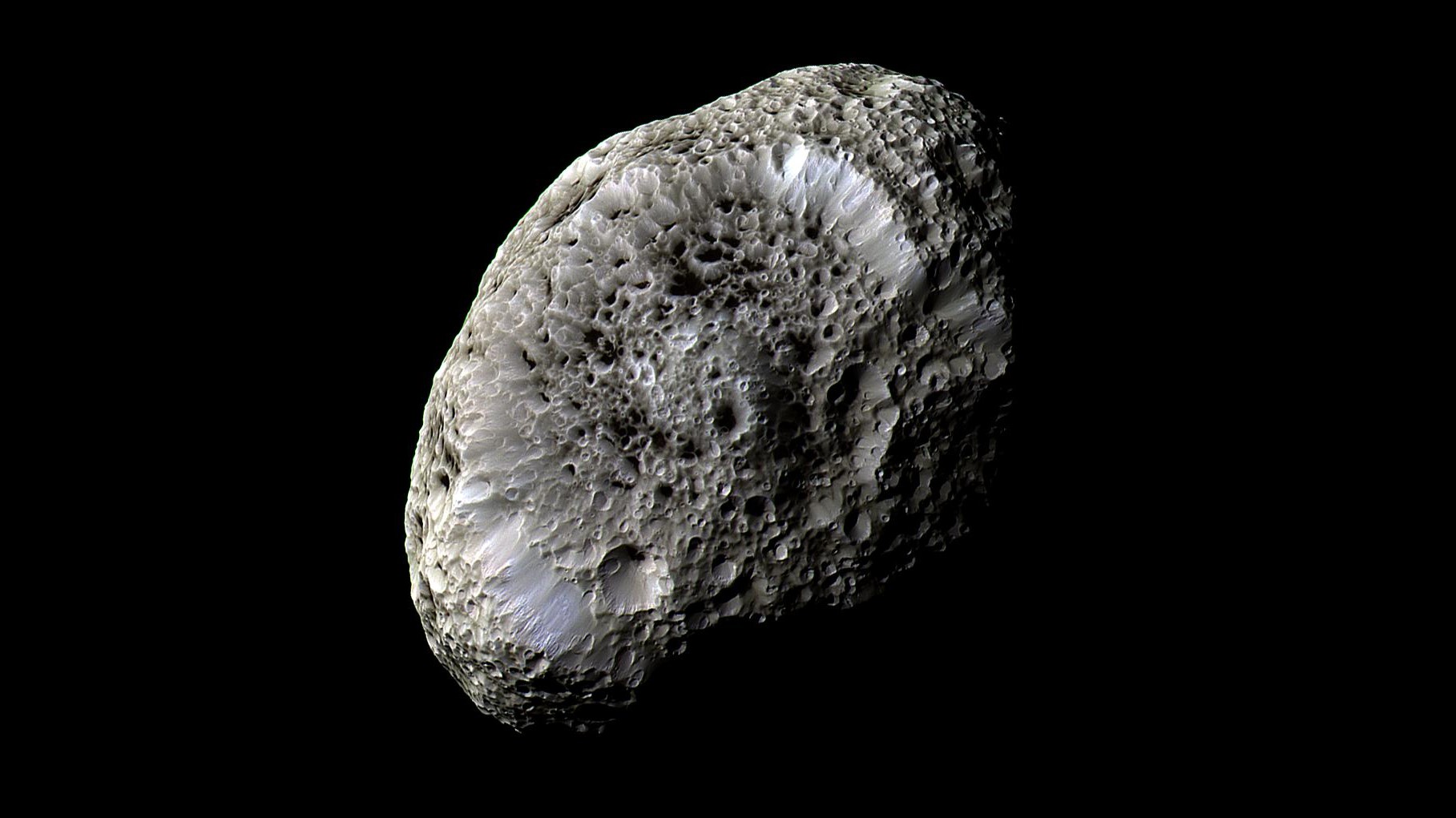

When the Cassini–Huygens mission arrived in the Saturnian system in 2004, it was greeted by a menagerie of mysterious moons with bizarre properties. Titan, the second largest moon in the solar system, is also the only moon in our cosmic neighborhood to sport an atmosphere, one redolent in organic molecules. Then, there's Hyperion, a battered and bruised body that looks like a giant pumice stone tumbling around Saturn. Meanwhile, the yin-yang world of Iapetus, with its two-toned hemispheres believed to result from passing through Saturn's E ring — which is formed by material spewed out from Enceladus's geysers — has the most inclined orbit of any of Saturn's main moons, angled at 15.5 degrees to Saturn's equatorial plane.

And of course there are Saturn's rings, unmatched in the solar system; their age is now thought to be a "young" 100 million years, but their origins have remained frustratingly mysterious.

Article continues belowNow, astronomers led by Matija Ćuk of the SETI Institute have come to suspect the creation of the Titan that we know today via a collision and merger of two moons could have triggered a series of events that led to all of Saturn's other peculiarities that we see today.

The clue to all this came from Cassini's measurements of Saturn's "moment of inertia," which is governed by the distribution of mass inside Saturn itself. This moment of inertia is a controlling factor in how much Saturn's axis of rotation wobbles, like a spinning top, a phenomenon known as precession. It had been thought that the period of Saturn's precession matched the period of distant Neptune's orbit, creating a gravitational resonance that began to pull Saturn over at an angle of 26.7 degrees relative to the plane of its orbit around the sun. This tilt has the added benefit of allowing us to see Saturn's rings more clearly from Earth.

But Cassini's measurements of the internal mass distribution showed that slightly more of Saturn's mass was concentrated in the center than had been thought. This therefore changes Saturn's moment of inertia, which takes it marginally out of resonance with Neptune's orbit.

Seemingly, something had pulled Saturn out of sync with Neptune, resulting in mass to become redistributed inside Saturn. But what could have done that?

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Despite being far less massive than Saturn, the ringed planet's moons can have a surprisingly large effect on the planet. Originally, to explain what took Saturn out of resonance with Neptune, scientists came up with a theory that once upon a time Saturn had another icy moon, which they named Chrysalis. This moon, they said, could have had its orbit perturbed following a close encounter with Titan and got too close to Saturn, where gravitational tidal forces ripped it apart about 100 million years ago. While most of the debris fell into Saturn, some remained in orbit, forming the rings. Meanwhile, the interaction with Chrysalis would have been the trigger to cause Titan's orbit to expand, which in turn would have pulled Saturn out of sync with Neptune.

It was a nice theory, but when Ćuk's team put it to the test in simulations, they found that the vast majority of the time Chrysalis collided with Titan instead. However, instead of being a dead end for the Chrysalis hypothesis, the simulations opened another door, and the key was another moon of Saturn, Hyperion, which orbits just beyond Titan.

Titan and Hyperion are another example of gravitational resonance. Their orbits are locked together: for every four orbits of Saturn that Titan makes, Hyperion makes exactly three orbits, tumbling disorderly around the ringed planet.

"Hyperion, the smallest among Saturn's major moons, provided us the most important clue about the history of the system," said Ćuk in a statement. "In simulations where the extra moon became unstable, Hyperion was often lost and survived only in rare cases. We recognized that the Titan–Hyperion lock is relatively young, only a few hundred million years old. This dates to about the same period when the extra moon disappeared. Perhaps Hyperion did not survive this upheaval, but resulted from it. If the extra moon merged with Titan, it would produce fragments near Titan's orbit. That is exactly where Hyperion would have formed."

Ćuk is suggesting that Chrysalis was real, and did indeed collide and merge with the proto-Titan 100–200 million years ago, and that it was this collision that shaped much of what we see in the Saturnian system.

For example, before the collision Titan may have been more like Jupiter's icy, airless moon Callisto, with an ancient and battered surface. The collision would have seen Titan's entire surface wiped clean, which would explain why there are so few craters on Titan beneath its thick atmosphere. And that atmosphere would have leaked out from Titan's interior during the collision. The collision knocked Titan in its orbit around Saturn, causing its orbit to widen and become more elongated. It is only now beginning to gradually grow more circular again.

The change in Titan's orbit would have seen its tidal forces wreak havoc on the inner mid—sized moons, prompting them to collide too, according to further simulations by scientists at the University of Edinburgh and NASA Ames Research Center. While the moons reformed from most of the debris, some of the icy particles would have settled around Saturn to form its ring systems.

The simulations also show that Chrysalis would have perturbed Iapetus's orbit, leading to its high inclination.

It is a nice, neat hypothesis — but currently, that is all it is. While the idea matches the facts, there's no direct evidence yet. NASA's Dragonfly mission to Titan, which is set to launch in 2028, could be the first to find such evidence by looking for further signs that Titan's surface is young, indicating the upheaval that followed the collision with Chrysalis over 100 million years ago.

The findings from Ćuk's team have been accepted for publication in Planetary Science Journal, and a preprint is available on the arXiv paper repository.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.