Russia's withdrawal from the International Space Station could mean the early demise of the orbital lab — and sever another link with the West

Future efforts will focus on a new a Russian space station.

This article was originally published at The Conversation. The publication contributed the article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

Wendy Whitman Cobb, professor of strategy and security studies at the US Air Force's School of Advanced Air and Space Studies

Editors note: On July 26, 2022, Russia announced its plan to withdraw from the International Space Station "after 2024." This article was published on that same day based on the statement from the head of Russia’s space agency. But since then, Russia appears to have changed its stance. A video posted by the Russian space agency and statements from a NASA official both indicated that Russia intends to continue operating the ISS with current partners until its own space station is complete. That station is scheduled to be operational sometime in 2028.

Russia intends to withdraw from the International Space Station after 2024, according to an announcement from Yuri Borisov, the new head of the Russian space agency, Roscosmos, in a meeting with Vladimir Putin on July 26, 2022. Borisov also said future efforts will focus on a new a Russian space station.

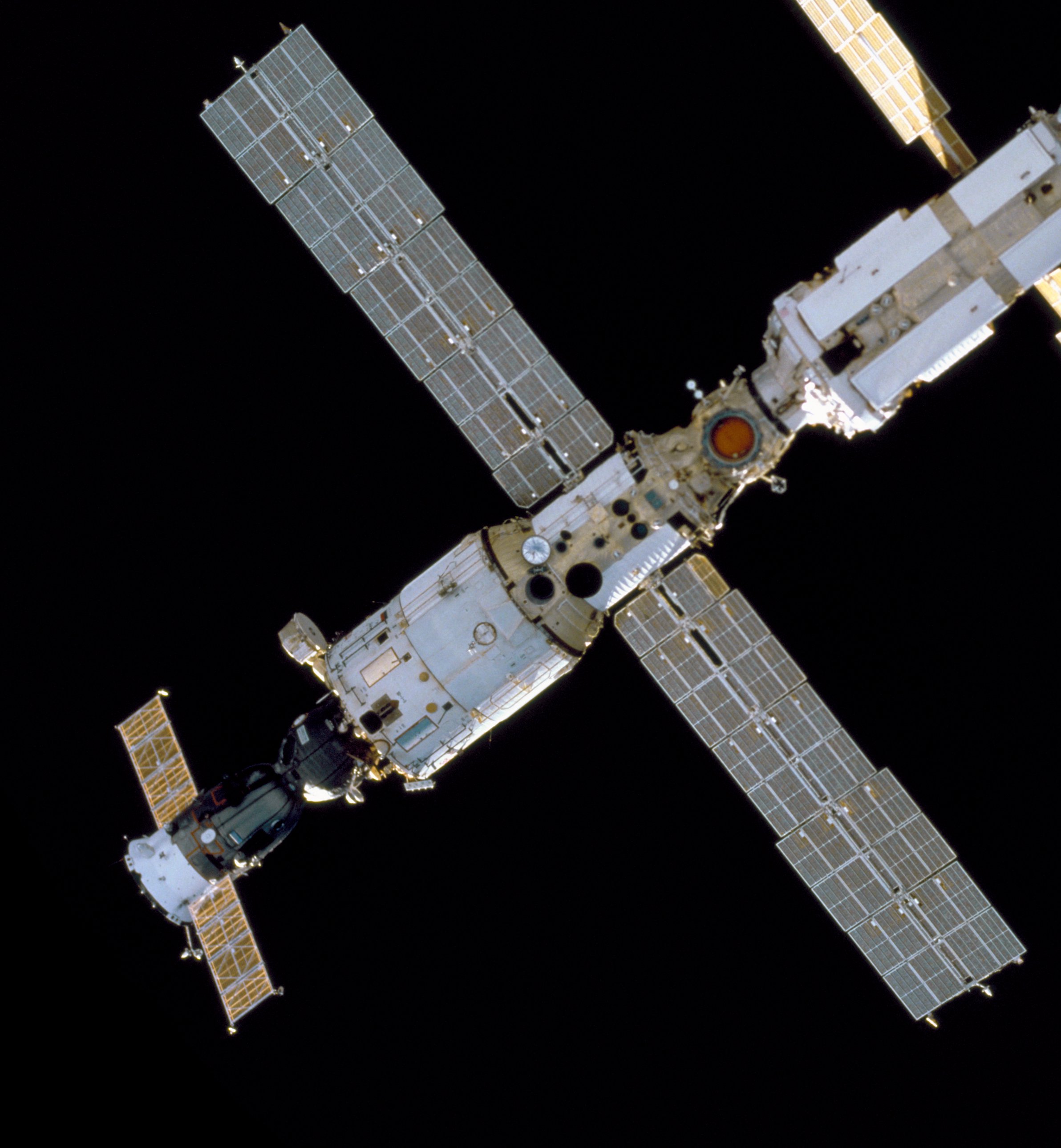

Current agreements on the ISS have it operating through 2024, and the station needs Russian modules to stay in orbit. The U.S. and its partners have been seeking to extend the station’s life to 2030. Russia's announcement, while not a breach of any agreement or an immediate threat to the station's daily operation, does mark the culmination of months of political tensions involving the ISS.

Over its 23-year lifetime, the station has been an important example of how Russia and the U.S. can work together despite being former adversaries. This cooperation has been especially significant as the countries' relationship has deteriorated in recent years. While it remains unclear whether the Russians will follow through with this announcement, it does add significant stress to the operation of the most successful international cooperation in space ever. As a scholar who studies space policy, I think the question now is whether the political relationship has gotten so bad that working together in space becomes impossible.

What would this withdrawal look like?

Russia operates six of the 17 modules of the ISS – including Zvezda, which houses the main engine system. This engine is vital to the station’s ability to remain in orbit and also to how it moves out of the way of dangerous space debris. Under the ISS agreements, Russia retains full control and legal authority over its modules.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It is currently unclear how Russia’s withdrawal will play out. Russia’s announcement speaks only to "after 2024." Additionally, Russia did not say whether it would allow the ISS partners to take control of the Russian modules and continue to operate the station or whether it would require that the modules be shut down completely.

Given that the Russian modules are necessary to station operations, it's uncertain whether the station would be able to operate without them. It's also unclear whether it would be possible to separate the Russian modules from the rest of the ISS, as the entire station was designed to be interconnected.

Depending on how and when Russia decides to pull out of the station, partner countries will have to make tough choices about whether to deorbit the ISS altogether or find creative solutions to keep it in the sky.

A continuation of political tensions

The announcement of the withdrawal is the latest in a series of events concerning the ISS that have occurred since Russia first invaded Ukraine in February. Russia's decision to leave should not have a significant effect on the daily function of ISS. Like a number of minor incidents that have happened over the previous months, it is more of a political action.

The first incident occurred in March, when three Russian cosmonauts emerged from their capsule in yellow and blue flight suits that were similar in color to the Ukrainian flag. Despite the resemblance, Russian officials never spoke about the coincidence. Then, on July 7, 2022, NASA publicly criticized Russia for apparently staging a propaganda photo. In the photo, the three Russian cosmonauts pose with flags associated with regions in eastern Ukraine occupied by Russian forces.

There have been no disruptions to the operation of the station itself. Astronauts on the station continue to perform dozens of experiments every day, as well as carrying out joint spacewalks. But one substantial effect of the increasing tensions was the end of Russian participation in joint experiments with European nations aboard the ISS.

With little information available about how Russia's withdrawal will affect the use of its modules, in the short term, it seems likely that the largest effects will be on scientific experiments.

Why now?

It's unclear why Russia made this announcement now.

Tensions surrounding the ISS have been high since Russia's invasion of Ukraine began in February 2022. At the time, Dmitry Rogozin, then head of Roscosmos, insinuated that Russia’s leaving the ISS might be a possibility. However, Rogozin was recently fired, and NASA and Roscosmos announced a seat swap for the ISS. Under this deal, an American astronaut would launch to the station on a future Soyuz mission while a cosmonaut would launch on an upcoming SpaceX Dragon launch. The two moves together suggested that the two sides might still be able to find ways to work together in space. But it seems those impressions were misleading.

The announcement also comes as the U.S. is considering the future beyond the ISS. NASA is currently in the first phase of development of a commercial space station as a replacement for the orbiting lab. While accelerating the development of this new space station would be difficult, it does signal that the ISS is nearing the end of its productive and inspirational life, no matter what Russia does.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook and Twitter. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher.

I received a BA in political science (summa cum laude and university honors) and an MA in political science from the University of Central Florida. I received a Ph.D. in political science from the University of Florida where my research focused on the intersection of political institutions and public policy. I have authored several books including Unbroken Government: Success and Failure in Policymaking (Palgrave Macmillan, 2013), The Politics of Cancer: Malignant Indifference (Praeger, 2017), and The CQ Press Career Guide for Political Science Students (CQ Press, 2017). My research has also appeared in journals including Congress and the Presidency, Space Policy, and the Journal of Political Science Education. I am currently professor of strategy and security studies at the US Air Force's School of Advanced Air and Space Studies, a selective graduate program for Air Force officers. Prior to my current position, I was associate professor of political science at Cameron University in Lawton, Oklahoma.