What actually happens to a spacecraft during its fiery last moments? Here's why ESA wants to find out

"Understanding how different materials behave as they burn up could help engineers design satellites that fully disintegrate, leaving nothing behind in orbit or in the atmosphere."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

What actually happens to a spacecraft during its fiery last moments? That's the key question for the European Space Agency's (ESA) Destructive Reentry Assessment Container Object (Draco) mission.

ESA has greenlit the program that will create a highly complex reentry of a spacecraft specifically built to dive into Earth's atmosphere while loaded with a variety of sensors.

As the Draco spacecraft falls into thicker and thicker air while it enters the atmosphere, it will collect data on how materials react and introduce pollutants into the upper stratosphere. In other words, it's an atmospheric stab for science.

Last moments

ESA is strongly backing an ambitious Zero Debris approach, an undertaking that aims to prevent more space debris by attempting to lower the risk that spacecraft will produce debris from collisions.

As part of that, ESA scientists are studying what happens when satellites burn up. Reentry science is an essential element of what's dubbed "design for demise" efforts, said Holger Krag, ESA Head of Space Safety.

"We need to gain more insight into what happens when satellites burn up in the atmosphere as well as validate our re-entry models," Krag said in an ESA statement focused on the Draco initiative.

"That's why the unique data collected by Draco will help guide the development of new technologies to build more demisable satellites by 2030," said Krag.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Strain gauge

Draco's sensors will be measuring temperatures, gauging the strain on the various parts of the satellite itself, and register the surrounding pressure. Four additional cameras will be pointing at the spacecraft to watch the destruction and collect contextual information.

Planned for 2027, the Draco satellite is anticipated to tip the scales at between 330 to 440 pounds (150-200 kilograms). About the size of a washing machine, Draco would purposely pile-drive itself over an ocean uninhabited area just some 12 hours after being put into Earth orbit.

Fiery frenzy

Outfitted with 200 sensors and 4 cameras to record its fiery frenzy, the 1.3 foot diameter (40 centimeters) capsule would store data safely onboard. Once its parachute is deployed, Draco would connect to a geostationary satellite, outputting its data.

According to ESA planners, there will be about a 20-minute window to transmit telemetry before it splashes down into the ocean, concluding the Draco mission's assignment.

If all goes well, Draco would collect "real-world data" on what occurs as space hardware takes the heat, shatters and scatters during reentry. It's a process that researchers can only mimic today on Earth in wind tunnels or via computer models.

"Understanding how different materials behave as they burn up," ESA explains, "could help engineers design satellites that fully disintegrate, leaving nothing behind in orbit or in the atmosphere."

Ablation products

The case for Draco data is front-and-center explain space debris experts.

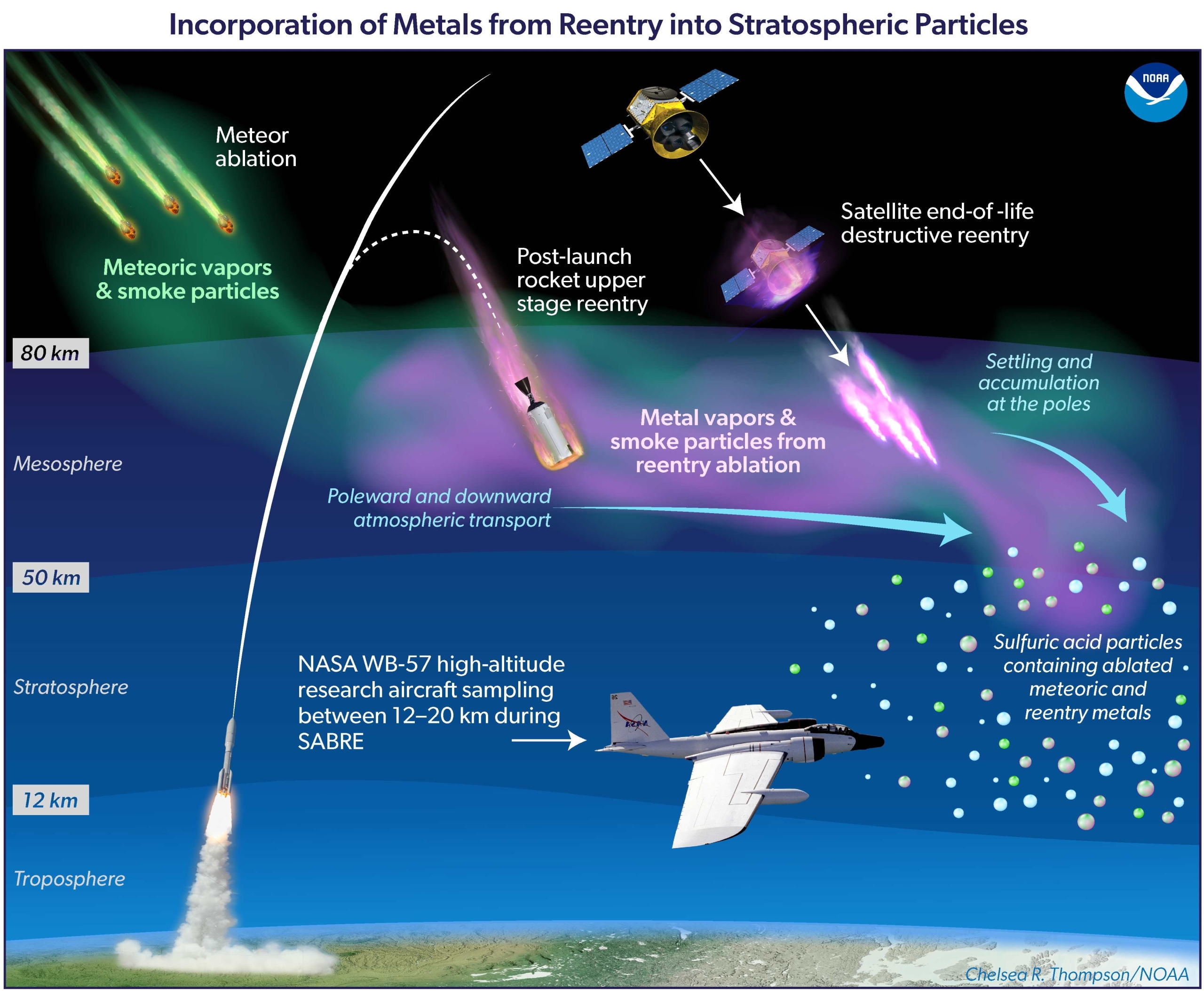

"Reentries create several issues for general space sustainability," said Aaron Boley, a professor at the University of British Columbia for physics and astronomy and co-director of the Outer Space Institute.

If uncontrolled, they impose casualty risks to people on the ground and in aircraft in flight, Boley told Space.com, and can further be disruptive to air traffic should there be sudden airspace closures in reaction to the reentries.

"They also deposit ablation products directly into the upper atmosphere," Boley said.

One approach to addressing casualty risks is to design spacecraft to demise entirely, but this exacerbates the atmosphere pollution problem, said Boley. "Moreover, reentry ablation models are insufficiently verified due in part to limits on lab testing."

Complex problems: safety and pollution

Experiments that can monitor the on-the-spot demise of a satellite and the types of emission products that are produced upon reentry are very valuable for addressing the interconnected and complex problems of safety and pollution, Boley added.

While not taking part in the Draco project, Boley said that characterizing the types of ablation products "is of high priority" as doing so enables investigators "to better understand how reentry emissions will affect upper atmosphere aerosols and associated chemistry, with implications for ozone, climate balance, upper atmosphere polar clouds, and atmospheric transmission," said Boley.

Piece of the puzzle

Leonard Schulz is a researcher at the Technische Universität Braunschweig's Institute of Geophysics and Extraterrestrial Physics in Braunschweig, Germany.

Also not engaged in ESA's Draco initiative, Schulz said that the results of the undertaking would be eagerly awaited.

"In-situ measurements are one important piece of the puzzle missing to better understand destructive spacecraft re-entry and its effects on the atmosphere," he told Space.com.

"I look forward to the results of this mission. Hopefully, it can serve as a pathfinder for in-situ observations of spacecraft fragmentation and especially their ablative behavior," said Schulz.

Relevant data

Similar in view is Luciano Anselmo, a researcher at the Space Flight Dynamics Laboratory within the National Research Council's Institute of Information Science and Technologies in Pisa, Italy.

Draco will be a single spacecraft reentry, with a specific trajectory, mass, and design, Anselmo said.

Not involved in the Draco program, Anselmo told Space.com that the experiment aims to be as representative as possible and, if successful, will allow for the collection of a lot of relevant data.

"This data could not only prove to be much more generally applicable than one might initially think," said Anselmo, "but could also reveal something unexpected, fostering new lines of investigation."

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.