Edgar Mitchell, Sixth Astronaut to Walk on the Moon, Dies at 85

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

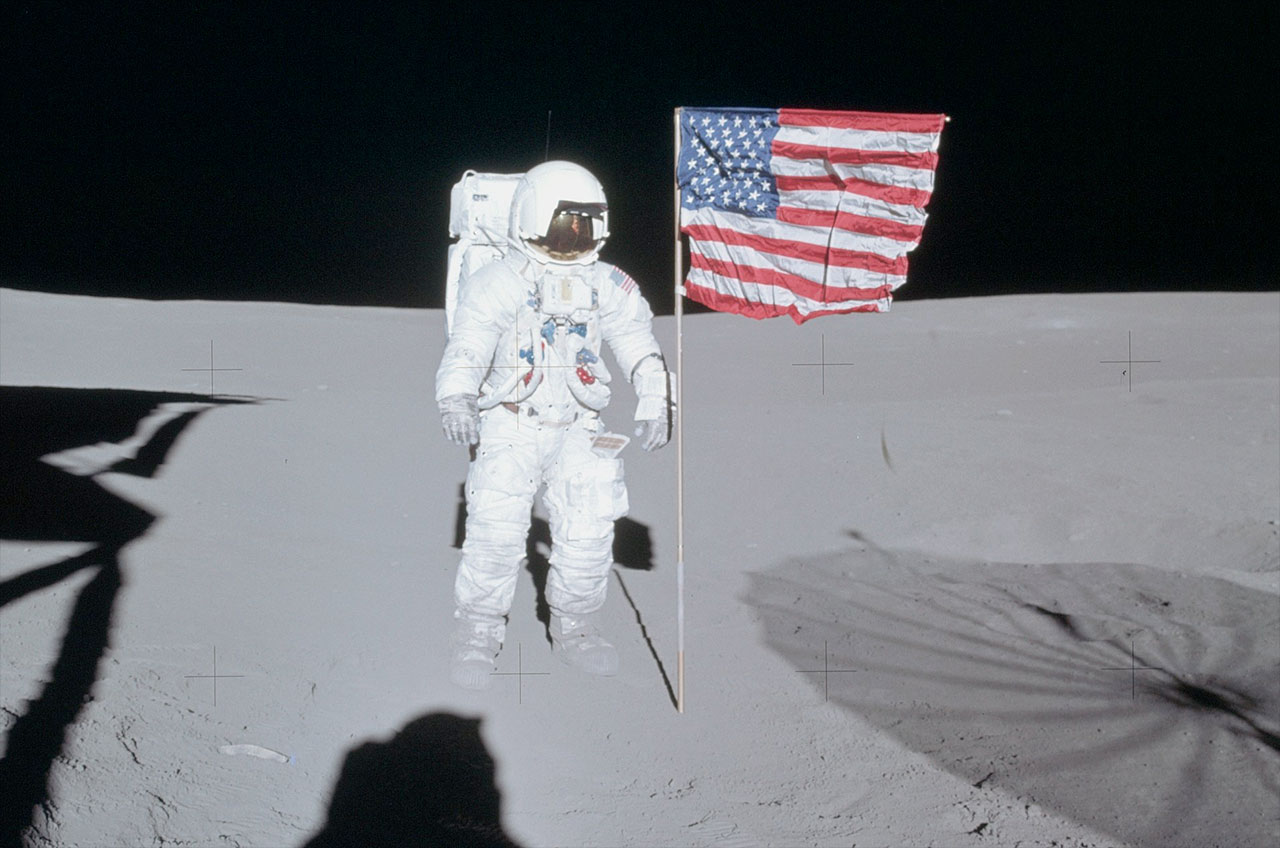

Edgar Mitchell, who 45 years ago became the sixth man to walk on the moon, died on Thursday (Feb. 4), the day before the anniversary of his lunar landing. He was 85.

The lunar module pilot on board NASA's Apollo 14 mission in 1971, Edgar Mitchell died peacefully in his sleep after a short illness at a hospice facility located near his home in West Palm Beach, Fla., his family confirmed.

"He was a hero in the classical sense," Karlyn Mitchell, the astronaut's oldest daughter, said in statement. "Though he fulfilled his childhood dreams while still a young man, he managed to sustain an aura of excitement by evolving and reinventing himself. He never tired of encouraging others to strive and explore." [Edgar Mitchell: The Sixth Man on the Moon]

"My brother and sisters consider ourselves so blessed to have had the Dad we did," added Kimberly Mitchell, oldest of his adopted children. "He was incredibly generous with his heart and his brain, making each of us a better person because we knew him and were shaped by him."

For nine hours over the course of two moonwalks, Mitchell explored the Fra Mauro highlands with the commander of Apollo 14, Alan Shepard. Flying to and from the moon with Stuart Roosaon the command module Kitty Hawk, Mitchell and Shepard achieved the third U.S. moon landing on Feb. 5, 1971, but not before problems aboard the lunar module Antares almost caused an abort, twice.

'Whew, that was close'

"We noticed as we were on our last circuit of the moon before starting down, while checking out the lunar module and getting ready, that the abort light came on in the lunar module," said Mitchell in a 1997 NASA interview. "And that was a surprise. It shouldn't do that."

The false signal was about to become a real problem after the descent engine fired, as it would have led the on board computer to command an auto-abort. After a scramble by flight controllers back on Earth, Mitchell was able to enter a software fix, comprising more than 80 keystrokes, just in time.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We had something like 30 seconds to spare when we got all of that done, and we started de-orbit then and fired the engines to start down, with just a few seconds left to spare and it worked," Mitchell recounted. [How NASA's Apollo Moon Landings Worked (Infographics)]

It was not long though, before another problem arose.

"It was one crisis to the next in that last two hours," said Mitchell. "When we got down to 20,000 feet [6,100 m], we had no landing radar, and that caused another emergency with about 90 to 100 seconds to go ... because we had to – at 10,000 feet [3,050 m] – abort if we didn't have landing radar."

Fortunately, a call from the ground to try cycling the radar's circuit breaker worked, restoring access to the altitude and vertical descent speed data needed to safely land.

"Whew, that was close," Mitchell radioed Mission Control.

Less than six minutes later, the Antares had safely landed, and less than six hours later, Mitchell was on the surface.

"Okay, Ed. We can see you coming down the ladder now," Mission Control radioed as Mitchell followed Shepard onto the lunar surface.

"And it's very great to be coming down," replied Mitchell, before he jumped off the ladder's bottom rung to the lunar module's footpad. "That last one is a long one."

A climb and a throw

Deploying scientific instruments and collecting almost 95 pounds (43 kilograms) of moon rocks — in part by using a pull cart (the modular equipment transporter, or informally, the "lunar rickshaw") only used on Apollo 14, Mitchell and Shepard came within 100 feet [30 m] of the rim of Cone Crater, a mission objective — without realizing how close they really were.

"Our positions are all in doubt now," reported Mitchell, after he and Shepard had climbed up the crater's side for some time. "What we were looking at was a flank ... but it wasn't really the top of ... it wasn't the rim of Cone. We have got a ways to go yet."

Ultimately, flight controllers directed pair to give up on the rim and return to the lunar module.

Before going back in inside though, Mitchell and Shepard allowed for a moment of levity. Shepard famously revealed his makeshift golf club, taking a couple of swings at "little white pellets." Not to be outdone, Mitchell became the first and only javelin thrower on the moon.

"When Alan hit his golf balls and I kvetched... I then picked up the staff from the solar wind experiment, which we had already folded up and put in the return bay, and used that tall staff as a javelin and threw it after his golf ball," Mitchell recounted.

Mitchell, Shepard and Roosa returned to Earth on Feb. 9, 1971. On their way home, Mitchell, without the knowledge of his fellow crew mates, privately conducted extrasensory perception (ESP) experiments, which became public after they splashed down.

"It was in the paper, and [Shepard] was laughing and said, 'Ed, what's this all about?'" Mitchell described in the NASA interview. "I said, 'Sorry, boss. That's the way it happened.'"

Shepard responded with an expletive.

"That was his response, and nothing more was ever said," Mitchell recalled, laughing.

With Apollo 14 back on the Earth, Mitchell logged a total of nine days and one hour in space, 33 hours and 31 minutes of it on the moon. It was his only spaceflight.

Aiming for space

Born Sept. 17, 1930 in Hereford, Texas, Edgar Dean Mitchell considered Artesia, New Mexico his hometown.

Mitchell received bachelor of science degrees in industrial management and aeronautical engineering from Carnegie Institute of Technology in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and the U.S. Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California in 1952 and 1961 and a doctorate in aeronautics and astronautics from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1964.

He entered the U.S. Navy in 1952 and was commissioned as an ensign a year later. He completed flight training and was assigned to Patrol Squadron 29 deployed to Okinawa. Assigned to Heavy Attack Squadron Two in 1957, he flew off the aircraft carriers USS Bon Homme Richard and USS Ticonderoga.

It was also in 1957, with the former Soviet Union's launch of the world's first satellite, that Mitchell knew he wanted to be an astronaut.

"I was on a carrier in the Pacific, just about to come back to the States for some test pilot work, and when Sputnik went up I realized humans were going to be right behind it, so I started orienting my career toward that at that time," Mitchell said.

To gain the qualifications he thought would be attractive to NASA, he served as a research pilot and as the chief of the project management division of the Navy field office for the military's Manned Orbiting Laboratory (MOL) project.

"Although I was flying as a test pilot in research and R&D programs, I also finagled my way to Edwards [AFB, Calif.], where I went through their space school while I was also an instructor for the MOL astronauts," Mitchell described.

Apollo 13, before Apollo 14

It took nine years, but in 1966 he was selected as a NASA astronaut with the agency's fifth group of trainees, dubbed the "Original 19." His classmates included Roosa, as well as future moonwalkers Charles Duke and James Irwin.

Prior to his own flight assignment, Mitchell served on the support crew for Apollo 9 and as backup lunar module pilot for Apollo 10, the latter a dress rehearsal for the first lunar landing.

Originally assigned to fly on Apollo 13, Mitchell, along with Shepard and Roosa, were moved to Apollo 14 to give the almost all-rookie crew more time to train (Shepard, the first American astronaut in space, had only 15 minutes of flight time on his Mercury mission).

When the Apollo 13 crew launched and "had a problem" in April 1970, Mitchell worked in a simulator to figure out how to fly the lunar module with a command module attached.

"We'd never done that before," recalled Mitchell. "It wasn't obvious that we knew how to do it."

"How were these guys going to manually fly that monster and get home?" he said.

For his work, Mitchell was honored alongside other Apollo 13 team members by President Nixon with the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian award of the United States.

Following his own successful Apollo 14 flight to the moon, Mitchell served as a backup for the Apollo 16 crew before retiring from NASA and the U.S. Navy in 1972.

Last of his crew

Building on his earlier interest in ESP, Mitchell founded the Institute of Noetic Sciences in 1973 to sponsor research in the nature of consciousness and other phenomena. In that role, Mitchell spoke about his belief in UFOs, though noted he had never seen one personally.

Mitchell co-founded the Association of Space Explorers, a professional society for the international community of men and women who had flown into space, and served on the board of directors of the Astronaut Scholarship Foundation which awards students pursuing science and engineering degrees.

Mitchell authored several books, including "The Way of the Explorer" and a children's book, "Earthrise: My Adventures as an Apollo 14 Astronaut."

In addition to the Medal of Freedom, Mitchell was awarded NASA and U.S Navy distinguished service medals, among other honors. He was inducted into the International Space Hall of Fame in 1979 and the U.S. Astronaut Hall of Fame in 1997.

In 2006, NASA presented Mitchell with a moon rock, as a part of the agency's Ambassador of Exploration award. He in turn donated the award for display at the South Florida Science Museum in West Palm Beach.

With Mitchell's death, all three members of the Apollo 14 crew are now deceased (Roosa died in 1994 and Shepard died in 1998). Mitchell's passing now leaves only seven of the 12 Apollo astronauts who walked on the moon living.

Mitchell is survived by two daughters, Karlyn Mitchell and Elizabeth Kendall; his adopted children Kimberly Mitchell, Paul Mitchell and Mary Beth Johnson; nine grandchildren and one great-grandchild. Mitchell was preceded in death by his son, Adam B. Mitchell.

See more photographs of Edgar Mitchell, Apollo 14 moonwalker, at collectSPACE.com.

Follow collectSPACE.com on Facebook and on Twitter at @collectSPACE. Copyright 2015 collectSPACE.com. All rights reserved.

Robert Pearlman is a space historian, journalist and the founder and editor of collectSPACE.com, a daily news publication and community devoted to space history with a particular focus on how and where space exploration intersects with pop culture. Pearlman is also a contributing writer for Space.com and co-author of "Space Stations: The Art, Science, and Reality of Working in Space” published by Smithsonian Books in 2018.

In 2009, he was inducted into the U.S. Space Camp Hall of Fame in Huntsville, Alabama. In 2021, he was honored by the American Astronautical Society with the Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History. In 2023, the National Space Club Florida Committee recognized Pearlman with the Kolcum News and Communications Award for excellence in telling the space story along the Space Coast and throughout the world.