NASA Is Studying How to Mine the Moon for Water

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

There's a lot of water on the moon, and NASA wants to learn how to mine it.

Space agency scientists are developing two separate mission concepts to assess, and learn how to exploit, stores of water ice on the moon and other lunar resources. The projects — called Lunar Flashlight and the Resource Prospector Mission — are notionally targeted to blast off in 2017 and 2018, respectively, and aim to help humanity extend its footprint out into the solar system.

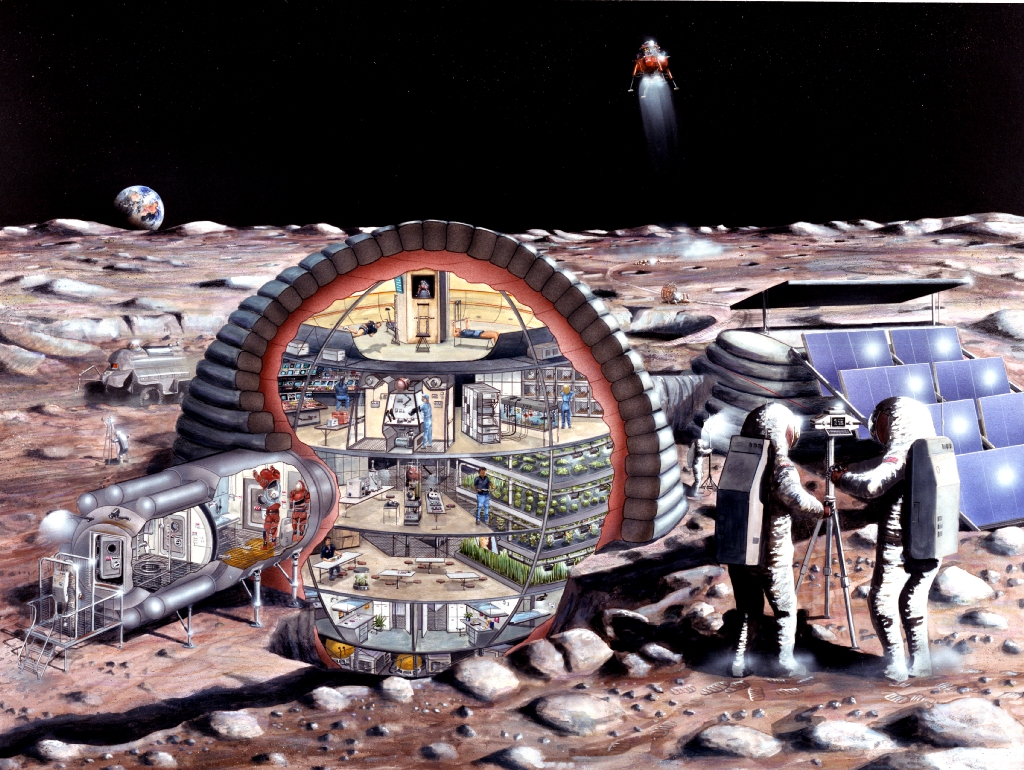

"If you're going to have humans on the moon and you need water for drinking, breathing, rocket fuel, anything you want, it's much, much cheaper to live off the land than it is to bring everything with you," said Lunar Flashlight principal investigator Barbara Cohen, of NASA's Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. [How to Build a Lunar Colony (Infographic)]

It's therefore important to "understand the inventory of volatiles across the whole moon and their purity, and their accessibility in particular," Cohen said in July during a presentation at the NASA Exploration Science Forum, a conference organized by the Solar System Exploration Research Virtual Institute at the agency's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California.

Solar sailing to the moon

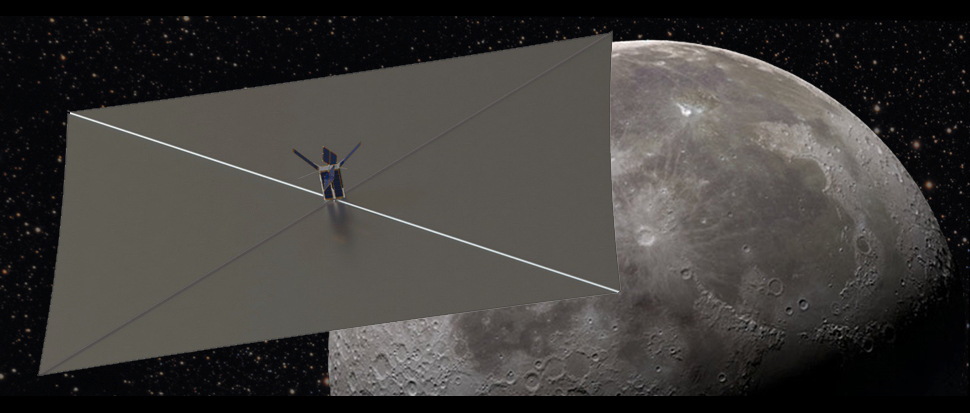

Lunar Flashlight is working toward a possible launch date in December 2017, when it would blast off on the first test flight of NASA's Space Launch System megarocket, along with several other piggybacking payloads.

Lunar Flashlight is a CubeSat mission, meaning the body of the spacecraft is tiny — about the size of a cereal box, Cohen said. But after it's deployed in space, the probe would get much bigger by unfurling an 860-square-foot (80 square meters) solar sail. [Photos: Solar Sail Evolution for Space Travel]

The spacecraft would then cruise toward the moon on a circuitous route, propelled along by the photons streaming from the sun. Lunar Flashlight would start orbiting the moon about six months after its launch, then spend another year spiraling down to get about 12 miles (20 kilometers) from the lunar surface.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The probe would then make about 80 passes around the moon at this low altitude, measuring and mapping deposits of water ice in permanently shadowed craters near the lunar poles. It would do this science work with the aid of its solar sail.

"We're going to use it as a mirror," Cohen said. "We're going to take the sunlight, bounce it off the solar sail into the permanently shadowed regions, and we're going to use a passive infrared spectrometer to collect the light from the permanently shadowed regions in wavelengths that are indicative of water frost."

Lunar Flashlight aims to find water ice that would be accessible to future explorers, be they human or robotic.

"What we're looking for is water right at the surface," Cohen said. "Could humans or their vehicles go into a permanently shadowed region and just scoop up the regolith and use what's at the surface to be able to extract water ice?"

Such deposits could provide drinking water for potential manned lunar outposts. And moon water could also be split into its constituent hydrogen and oxygen — prime components of rocket fuel, which could then spur and support exploration even farther afield, advocates of moon mining say.

A water-mapping rover

While Lunar Flashlight would eye the moon from above, the Resource Prospector Mission (RPM) plans to send a rover onto the lunar surface to get an up-close look.

This rover would land at a yet-to-be-determined polar site and map surface and subsurface concentrations of hydrogen at two different locations, which would ideally be separated by at least 0.6 miles (1 km). RPM would use a neutron spectrometer to measure water concentrations up to 3.3 feet (1 m) underground and a near-infrared spectrometer to make its surface measurements.

The solar-powered rover would roll into permananently shadowed regions, relying on batteries to keep working in the dark. It would likely have an operational lifetime of about one week on the lunar surface, mission officials have said.

Like Lunar Flashlight, RPM is geared to help enable future exploitation of water ice on the moon.

"How is the water ice distributed in the soil?" RPM project scientist Tony Colaprete of NASA Ames said at the Exploration Science Forum event. "That's really what Resource Prospector is fundamentally about, is identifying, locating the 'ore' and understanding how to excavate it — how to get at it — and what does that cost in terms of energy."

The rover would also be equipped with a drill, allowing it to take samples from up to 3.3 feet (1 m) deep, Colaprete said. Collected samples would be heated up in an oven, and the volatile materials such as water liberated by this process would be identified and quantified.

RPM also plans to extract oxygen from lunar dirt in a demonstration of in-situ resource utilization (ISRU). (This oxygen can be combined with hydrogen carried onboard to create water.)

"We need to take the first steps in demonstrating off of this world utilization of material," Colaprete said. "There's a lot of technology demonstration in here that's not just applicable to the moon; it's applicable to any mission, to any surface where you want to manipulate materials."

Mars is one such place. Indeed, NASA is also planning to conduct an ISRU experiment on the Red Planet in the coming years. In July, agency officials announced that its next Mars rover, slated to blast off in 2020, will carry an instrument that will generate oxygen from the carbon-dioxide-rich Martian atmosphere.

More missions coming?

NASA isn't the only entity eyeing the moon's resources. A number of private firms, including Moon Express and Shackleton Energy Co., also aim to mine and process lunar water.

If Lunar Flashlight and RPM get off the ground — both missions are still in the concept phase and have yet to be officially approved by NASA — they could bring such dreams closer to reality, by providing a better understanding of the quantity, distribution and composition of water on the moon, Cohen said.

"This is a very broad strategic knowledge gap," she said. "We're taking a very, very small bite out of it. Resource Prospector is taking another bite out of it. There's probably many, many missions to come that are going to address this."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.