Can current space law handle the new space age?

The question is no longer if space governance must evolve, but how quickly it can keep pace with the realities of the new space age.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Global activity in Earth orbit is booming, with cheaper launch, growing megaconstellations and the emergence of commercial actors transforming space activities. But the legal framework underpinning these activities is stuck in the 1960s, raising the question of whether we need a new approach to tackle growing challenges that threaten the sustainable use of outer space.

Satellite megaconstellations like SpaceX's Starlink, an increasing cadence of moon missions, a growing interest in orbital data centers and military activities are creating governance challenges that are increasingly difficult for nations, as well as private operators, to manage collectively.

Even when there is agreement that something needs to be done on a given matter, such as preventing collisions between an ever-growing number of satellites, coming together and reaching agreement is tough. The main framework for space governance, the Outer Space Treaty, was formulated in 1967 during a Cold War era in which there were just a few state actors active in space, minimal space traffic and no private endeavors.

Article continues below"The Outer Space Treaty and a couple of subsequent treaties govern all international space law, but they were signed at a time when basically only the United States and the Soviet Union could go to space," said Ely Sandler, a Harvard Kennedy School fellow and author of a recent paper on outer space governance.

Sandler proposes a Conference of Parties (COP) approach — similar to processes used in climate, biodiversity and arms-control negotiations — for discussing and tackling key issues in space governance, aimed at driving dialogue and developing binding norms, before avoidable crises emerge. There are two main pillars of challenges, according to Sandler, that a COP for space could address.

"The first is areas where actually, pretty much all space actors agree, not only that something needs to be done, but also what needs to be done," he said. "It's just that we don't have a mechanism for making it universal and binding."

These areas include standardized protocols for deorbiting spacecraft, such as making sure that all satellites that go into orbit have the same way of deorbiting; space traffic management, including communication between objects and avoidance maneuvers; and developing a liability regime that would create economic incentives for companies not to pollute the space environment.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

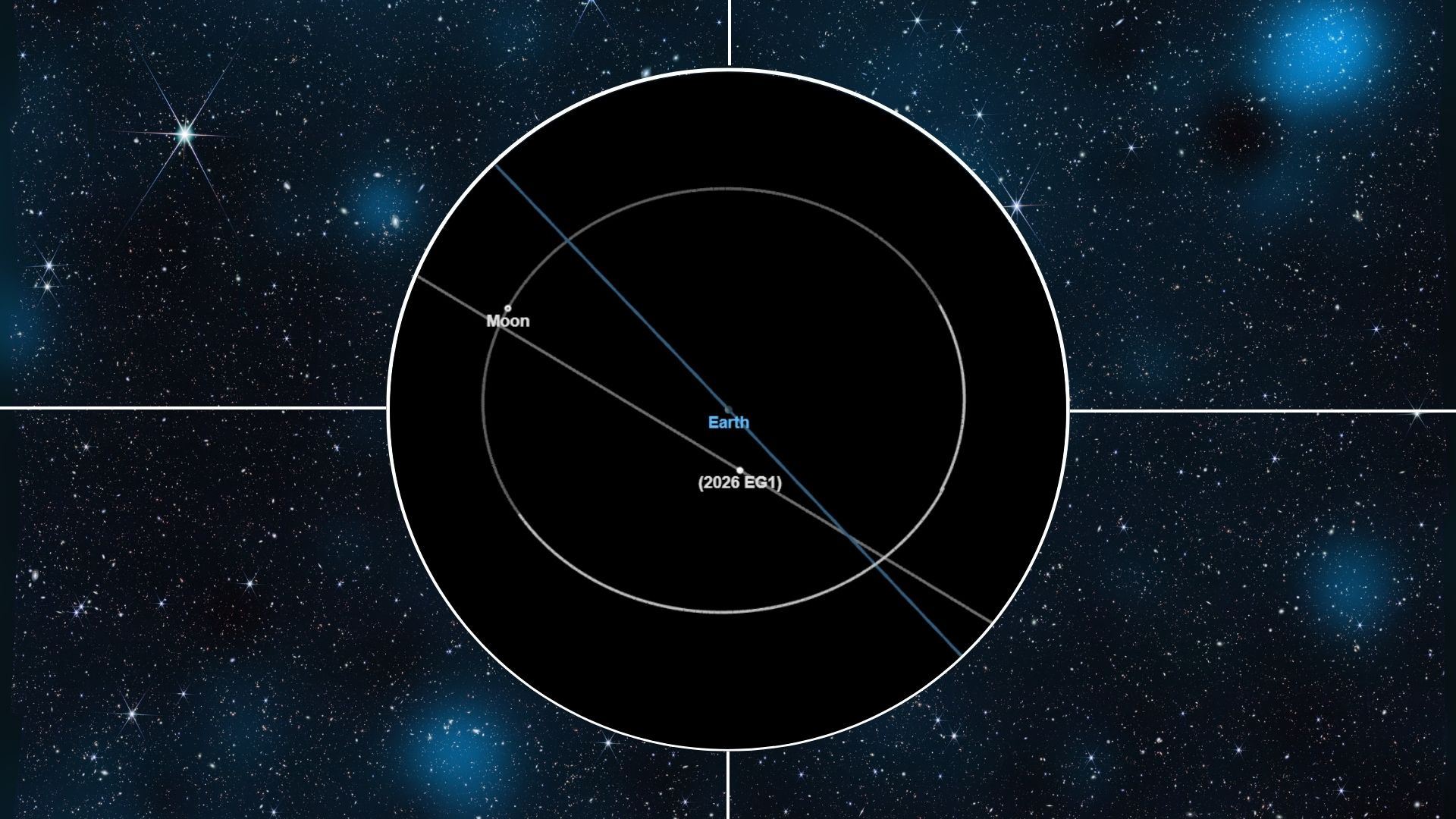

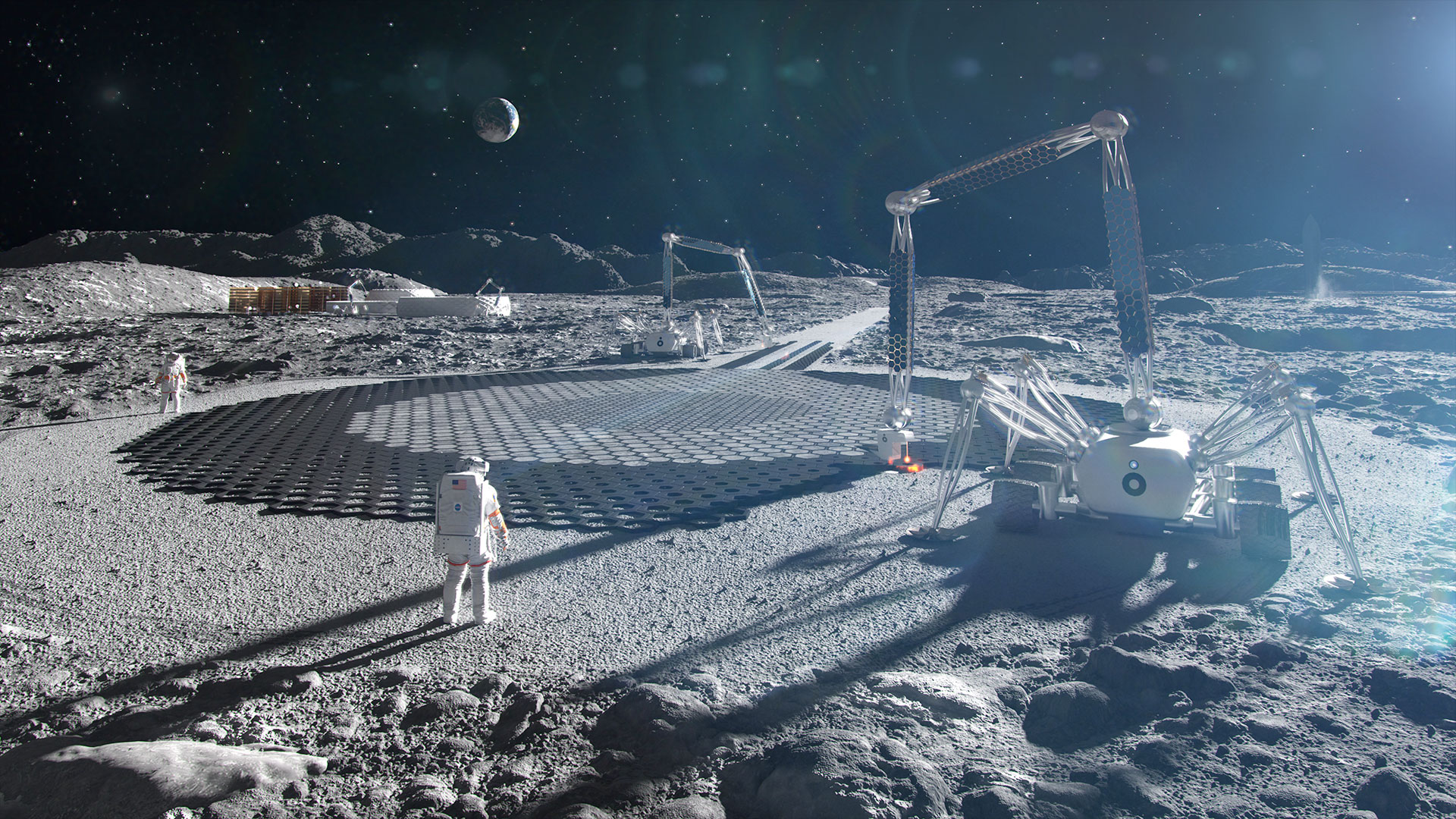

The second pillar would be issues of future concern, such as the mining of space resources and what would be deemed to be national appropriation of such resources (something prohibited by the Outer Space Treaty); and what the Artemis Accords refer to as safety zones — marking out an area in which another spacecraft should not enter, for example, once a vehicle has landed on the moon.

A COP approach with annual conferences would allow regular meetings of experts from various countries and stakeholders to convene and discuss these key issues, opening the way for incremental lawmaking on space, instead of relying on all-or-nothing treaties that require grand bargains between a diverse range of actors. It would also provide a politically more feasible pathway to interpreting and expanding the Outer Space Treaty, Sandler thinks.

He noted that, at present, there is something of a retreat from multilateralism globally — but that might not hold for outer space.

"International cooperation on space seems to be a little bit distinct from other areas where international cooperation has decreased," Sandler said. "We're still collaborating with the Russians on the International Space Station. There's still relatively productive debates at the United Nations Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space."

While the United States has recently pulled out of a number of United Nations processes and organizations, it is still engaged in many other multinational fora and organizations.

Still, the journey toward establishing a COP for space may take time. "It's very unlikely that, because of this paper, we institute a Conference of the Parties to the Outer Space Treaty in the next two or three years," Sandler said. "What we're trying to do is move the dialog away from our current options on space, as either some huge new treaty that would establish space, like Antarctica, as a neutral ground, or no cooperation at all."

A COP for space may not immediately inspire confidence in progress, given that the COP climate process regularly and prominently faces criticism from its disparate voices. While the environmental wing claims efforts have not gone far enough, for example, there are also those arguing that countries can’t be forced to decarbonize their economies.

And yet, Sandler said, much progress has been made since the U.N. Framework Convention on Climate Change treaty was signed in 1992, including binding emissions targets and shared understandings of greenhouse gases and their accounting.

Crucially, unlike climate policy, which requires costly economic transformation, space governance often involves relatively low-cost coordination measures, such as communications standards or deorbit plans.

As orbital activity accelerates and lunar exploration intensifies, the need for clearer rules is becoming harder to ignore. Whether through a COP or another mechanism, the question is no longer if space governance must evolve, but how quickly it can keep pace with the realities of the new space age.

Andrew is a freelance space journalist with a focus on reporting on China's rapidly growing space sector. He began writing for Space.com in 2019 and writes for SpaceNews, IEEE Spectrum, National Geographic, Sky & Telescope, New Scientist and others. Andrew first caught the space bug when, as a youngster, he saw Voyager images of other worlds in our solar system for the first time. Away from space, Andrew enjoys trail running in the forests of Finland. You can follow him on Twitter @AJ_FI.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.