As China and the US vie for the moon, private companies are locked in their own space race

"The way I like to think about space is not as an industry, but really as an eighth continent."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

As space becomes more crowded, more commercial and more consequential, the world has entered a new space race — and it bears little resemblance to the last one, industry leaders say.

Unlike the Cold War-era contest between the Soviet Union and the United States, which was driven by governments seeking to demonstrate technological superiority, today's race is increasingly powered by private companies and commercial competition. Falling launch costs, fueled largely by reusable rockets, have transformed access to low Earth orbit (LEO), turning it into a fast-evolving marketplace where companies compete and innovate at rapid speed.

That shift carries far-reaching implications for life on Earth, which now depends heavily on space-based assets, from climate monitoring and global communications to internet connectivity and navigation, experts said last month during a session at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

Article continues below"The way I like to think about space is not as an industry, but really as an eighth continent," said Dylan Taylor, CEO of Voyager Technologies, speaking to attendees on Jan. 22.

At the forefront of this transformation is the geopolitical competition between the United States and China centered on a return to the moon, a milestone poised to define the norms of space activity for decades ahead.

"The West absolutely is in a race with China to get back to the moon right now," said John Gedmark, CEO of San Francisco-based satellite company Astranis.

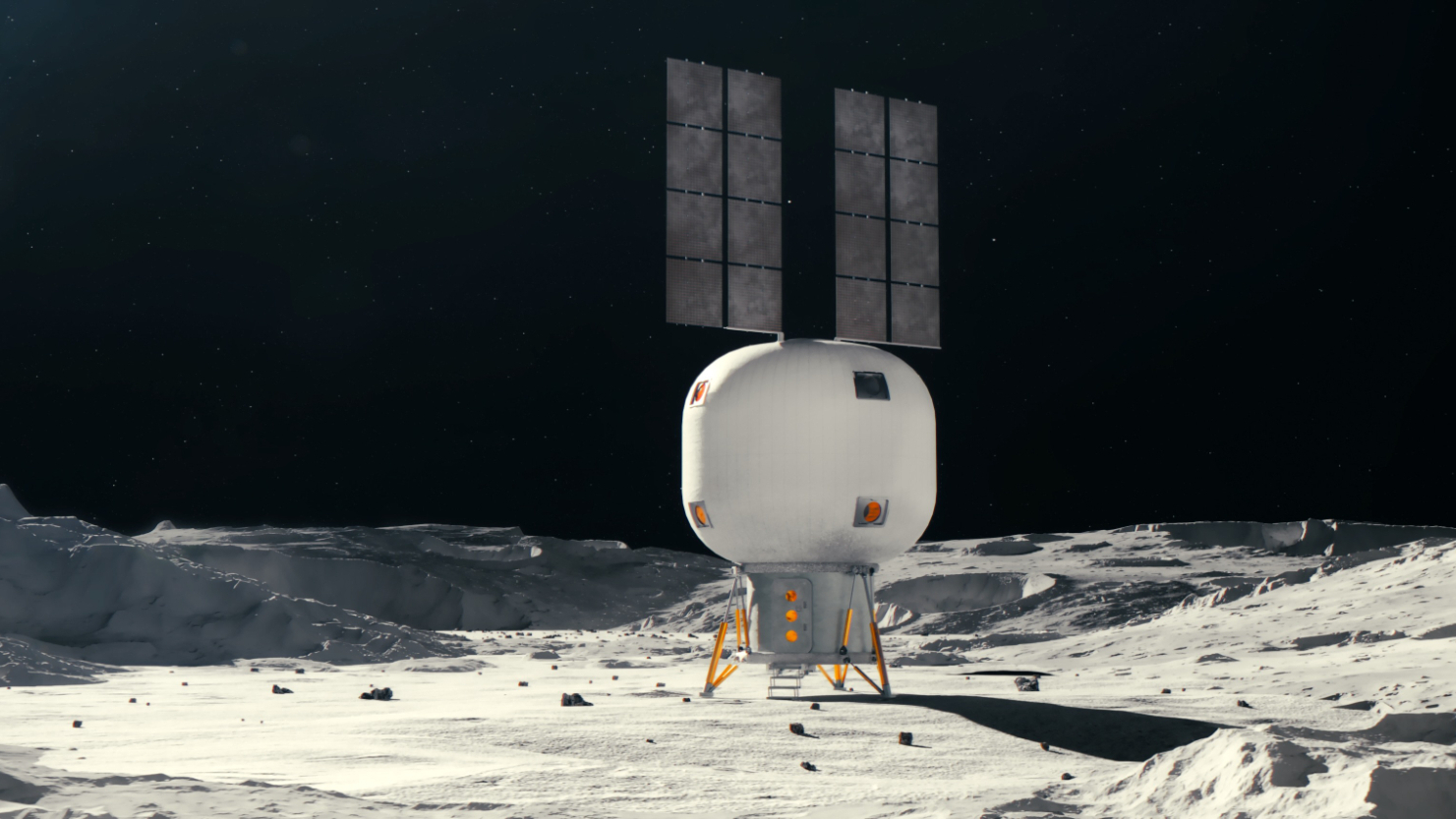

China has laid out an ambitious lunar plan to land astronauts on the moon before 2030, targeting the south pole, which contains water ice and other resources critical for long-term lunar exploration and settlement. NASA's Artemis 3 mission currently aims to land astronauts near the lunar south pole by 2028, following the Artemis 2 crewed lunar flyby that's targeted to launch in early March.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

China's plans for its well-funded space program also include expanding the Tiangong space station in LEO and accelerating Mars exploration. Chinese officials say the nation could return Mars samples to Earth as early as 2031 — potentially years ahead of U.S. efforts to retrieve samples collected by NASA's Perseverance rover in the Red Planet's Jezero Crater.

Some experts argue that China's steady execution has already given it an edge, while Western progress has been less consistent.

"We've been sort of all over the place," said Gedmark.

Still, he argued that the outcome remains uncertain, pointing to strong partnerships between the United States and Europe as well as key structural advantages, chief among them a powerful commercial space sector. "I think it's a very real open question today as to what's going to happen," Gedmark said.

Another major Western advantage, he added, is NASA's current leadership. He praised newly appointed Administrator Jared Isaacman as "the best candidate we've ever had for the position."

"I think we're gonna see things move very quickly in a way that I think will put the United States in a very good position," Gedmark said.

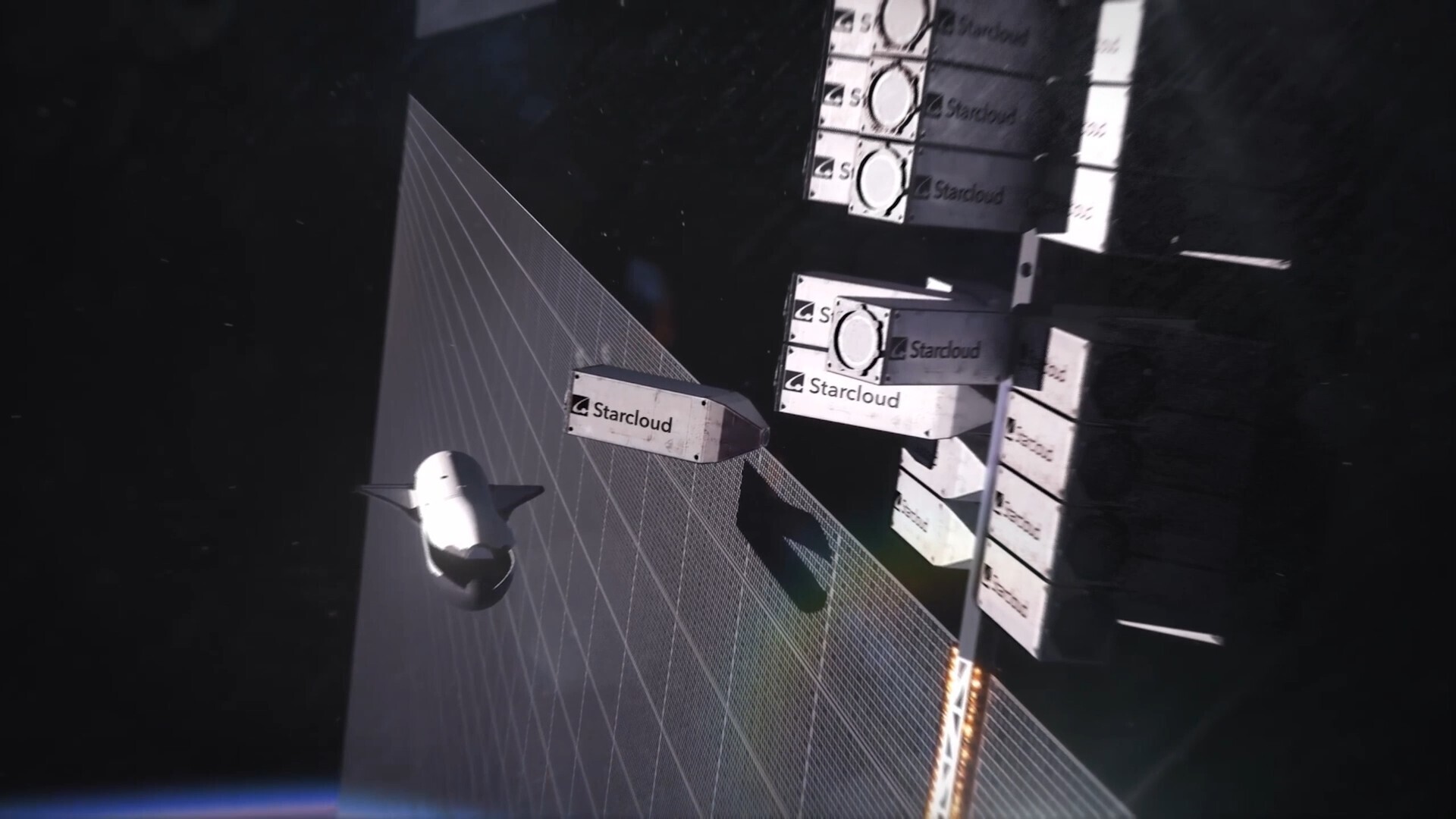

Beyond missions to the moon and Mars, Taylor said the next major leap in space will come from computing and data processing in orbit. Thanks largely to SpaceX, the industry now has the capability to place hardware in orbit reliably and at speed, effectively creating, as Taylor put it, "an elevator" to get hardware up.

Now, instead of sending vast amounts of raw data back to Earth for processing, a conventional process that's vulnerable to jamming and manipulation, companies are developing technologies that analyze information directly in space using onboard computing and artificial intelligence, then transmitting only the results, said Taylor.

"That's the next revolution happening," he said.

Sharmila Kuthunur is an independent space journalist based in Bengaluru, India. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She holds a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.