Scientists hunt for origins of the mysterious 'sun goddess' particle

It's the second most energetic cosmic ray ever to be detected striking Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

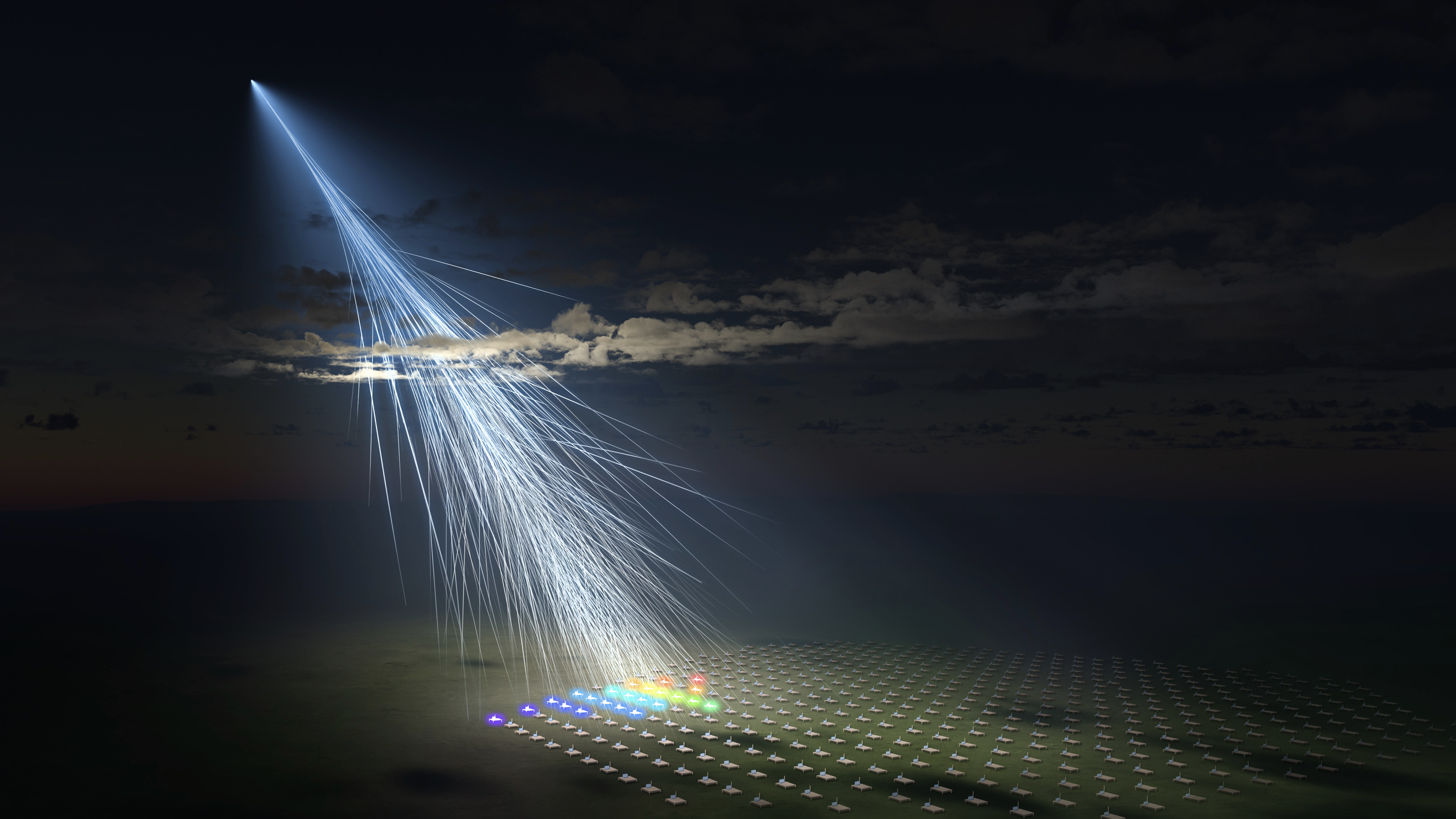

Scientists are investigating the origin of one of the most energetic particles ever seen hitting Earth from space. The Amaterasu particle, named for the Japanese sun goddess, was first detected in 2021, carrying 40 million times more energy than particles accelerated by the world's largest and most powerful particle accelerator, the Large Hadron Collider (LHC).

Amaterasu is an example of a cosmic ray, energetic charged particles that race through space at nearly the speed of light. It is the second most energetic cosmic ray ever detected after the "Oh-My-God" particle, detected in 1991. Such high-energy particles are extremely rare, which means scientists would very much like to understand their origins — currently thought to involve the wreckage of supernova explosions and central regions of galaxies dominated by feeding supermassive black holes.

Deepening the puzzle of Amaterasu is the fact that it seems to have emerged from the "Local Void," a region of space devoid of galaxies and the extreme environments and violent conditions thought be the factories that launch high-energy cosmic rays.

Article continues belowEnter Francesca Capel and Nadine Bourriche, researchers at the Max Planck Institute for Physics, who have found that Amaterasu's origins may not be locked within the local void. Instead, this highly energetic particle may have emerged from a range of relatively local cosmic environments.

"Our results suggest that, rather than originating in a low-density region of space like the Local Void, the Amaterasu particle is more likely to have been produced in a nearby star-forming galaxy such as M82," Bourriche said in a statement.

The duo's findings emerged from a novel data-driven approach that allowed them to trace the possible path of Amaterasu through the cosmos. The team considered the journey of this high-energy cosmic ray through space under the influence of magnetic fields using a statistical technique called in three dimensions called Approximate Bayesian Computation.

"This approach works by comparing the results of realistic, physics-based simulations with actual observational data to infer the most probable source locations," Bourriche said.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The result of this analysis was a collection of "probability maps" all tracking back to possible Amaterasu origin points beyond the Local Void. The research has implications beyond the origins of this extraordinary goddess particle, however. The team's findings could help better pin down which powerful and violent cosmic events serve as high-energy cosmic ray factories.

"Exploring ultra-high-energy cosmic rays helps us to better understand how the Universe can accelerate matter to such energies, and also to identify environments where we can study the behavior of matter in such extreme conditions," Capel said. "Our goal is to develop advanced statistical analysis methods to exploit the available data to its full potential and gain a deeper understanding of the possible sources of these energetic particles."

The team's results were published on Jan. 28 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.