Large Hadron Collider reveals 'primordial soup' of the early universe was surprisingly soupy

Waiter, there's a quark in my soup!

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Using the world's most powerful particle accelerator, CERN's Large Hadron Collider, scientists have discovered that the trillion-degree hot primordial "soup" that filled the cosmos for mere millionths of a second after the Big Bang actually behaved like a liquid, making it akin to a literal soup.

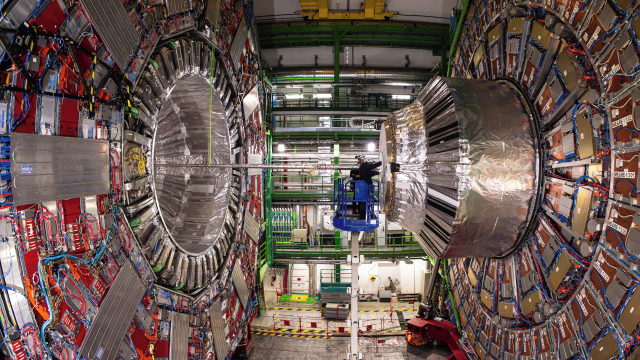

This primordial soup was composed of a plasma of particles called quarks and gluons that rapidly cooled, causing these two types of particles to fuse and create fundamental particles like protons and neutrons, which today sit at the heart of all atoms that make up the matter all around us. Today, quarks and gluons are only found locked up in the particles they comprise, with one exception. By smashing together heavy atoms of lead traveling at near-light speeds using the Large Hadron Collider (LHC), scientists can create a high-energy environment that briefly frees gluons and quarks from this atomic bondage, recreating the quark-gluon plasma of the early universe.

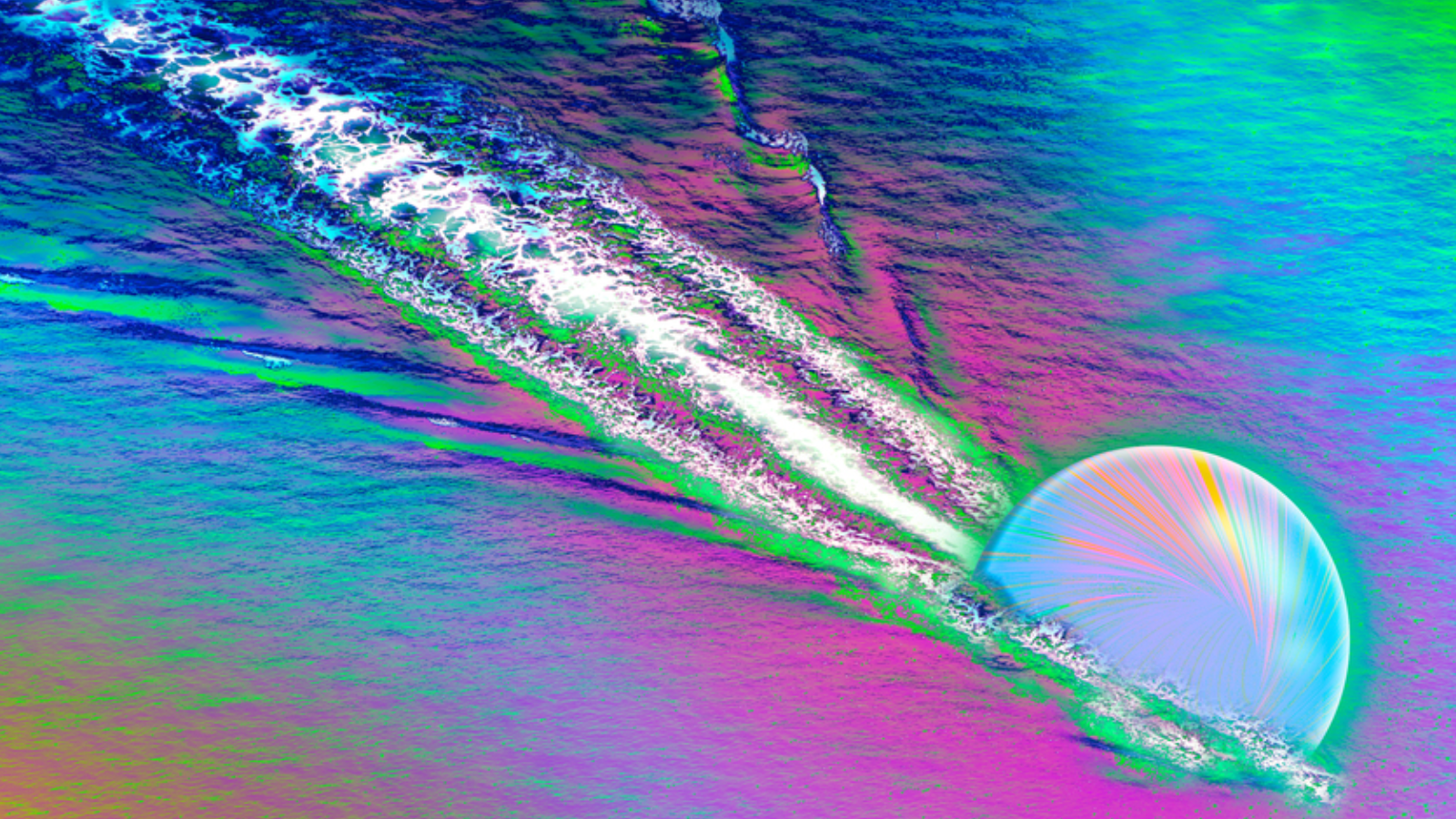

Using the 17-mile (27 kilometers) long accelerator located near Geneva, Switzerland, a team of researchers from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) generated quark-gluon plasma. Within this pseudo-primordial soup, they observed quarks creating "wakes" as they raced through the plasma, akin to the trail created by a boat as it travels through water. This is the first evidence that this quark-gluon plasma reacts to particles speeding through it in the same way that liquid does, splashing and rippling, acting as a single unified liquid rather than randomly scattering as individual particles would. This cohesion means the plasma-quark gluon wasn't just a fluid, a term which can include a liquid or a gas, but acted as a liquid. Scientists say it could settle some long-standing questions about what the universe's earliest 'stuff' was like.

"It has been a long debate in our field on whether the plasma should respond to a quark," team member Yen-Jie Lee, professor of physics at MIT, said in a statement. "Now we see the plasma is incredibly dense, such that it is able to slow down a quark, and produces splashes and swirls like a liquid. "So quark-gluon plasma really is a primordial soup."

To observe the wakes created in quark-gluon plasma by travelling particles, Lee and colleagues used the LHC's Compact Muon Solenoid (CMS) detector to develop a technique that also allowed them to measure the size, speed, and extent of these wakes, and how long it takes for them to ebb and dissipate. This information could be critical to better understanding both the properties of quark-gluon plasma and how it behaved during the first microseconds of the cosmos.

"Studying how quark wakes bounce back and forth will give us new insights on the quark-gluon plasma's properties," Lee said. "With this experiment, we are taking a snapshot of this primordial quark soup."

You might want to blow on this soup for a while

The quark-gluon plasma wasn't just the first liquid to have existed in the universe, but with a temperature of many trillions of degrees, it is also the hottest liquid that ever existed. The primordial soup is considered to have been a near-perfect liquid, which means its quark and gluon contents flowed together as a smooth, frictionless fluid.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Though there are many models of quark-gluon plasma, one theory, dubbed the "hybrid model," suggests that this primordial soup should react like any other liquid when particles pass through it at speed. In the hybrid model, a jet of quarks moving through the quark-gluon plasma should create a wake as it causes this plasma ocean to ripple and splash.

There have been many experiments at the LHC and other particle accelerators that have attempted to see this effect in action. Those experiments are only made possible through slamming heavy charged atoms, or heavy ions, together at near light-speed, which can generate a droplet of primordial soup that lives for no more than a quadrillionth of a second. Scientists continue to attempt to take snapshots of this primordial soup to understand the characteristics of quark-gluon plasma.

In the attempt to identify wakes in the quark-gluon plasma, scientists have been hunting for pairings of quarks and their antimatter counterparts known as anti-quarks. When a quark races through plasma, an anti-quark should exist, travelling at precisely the same speed but in the opposite direction. Both particles, according to the hybrid model, should create detectable wakes. Sounds simple enough, but there's a fly in this soup.

"When you have two quarks produced, the problem is that, when the two quarks go in opposite directions, the one quark overshadows the wake of the second quark," Lee explained. This team realized that finding the wake of a quark would be simpler if there were no second quark obscuring it.

"We have figured out a new technique that allows us to see the effects of a single quark in the quark-gluon plasma, through a different pair of particles," Lee added.

Boson croutons

Instead of hunting for quark pairs, Lee and colleagues looked for quarks travelling in unison with a neutral elementary particle called a Z-boson, which has little effect on its surroundings. The benefit of Z-bosons is that they have a specific energy, and that makes them comparatively easy to spot.

"In this soup of quark-gluon plasma, there are numerous quarks and gluons passing by and colliding with each other," Lee said. "Sometimes when we are lucky, one of these collisions creates a Z boson and a quark, with high momentum."

In these circumstances, the quark and Z-boson should slam into each other and bounce off in opposite directions, with the quark leaving a wake, but with the Z-boson not leaving one due to its lack of impact on the surrounding quark-gluon plasma. That means any ripples spotted in this situation are made by a quark alone.

After observing 13 billion LHC collisions, Lee and the team identified around 2,000 instances in which a Z-boson was produced. During these events, the scientists consistently observed a fluid-like pattern of splashes travelling in the opposite direction of the Z bosons they detected. That, they determined, was the sought-after quark wake effect. Indeed, the patterns observed conformed to ripple-predictions made by the hybrid model of quark-gluon plasma.

"We've gained the first direct evidence that the quark indeed drags more plasma with it as it travels," Lee concluded. "This will enable us to study the properties and behavior of this exotic fluid in unprecedented detail."

The team's research was published in the journal Physics Letters B.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.