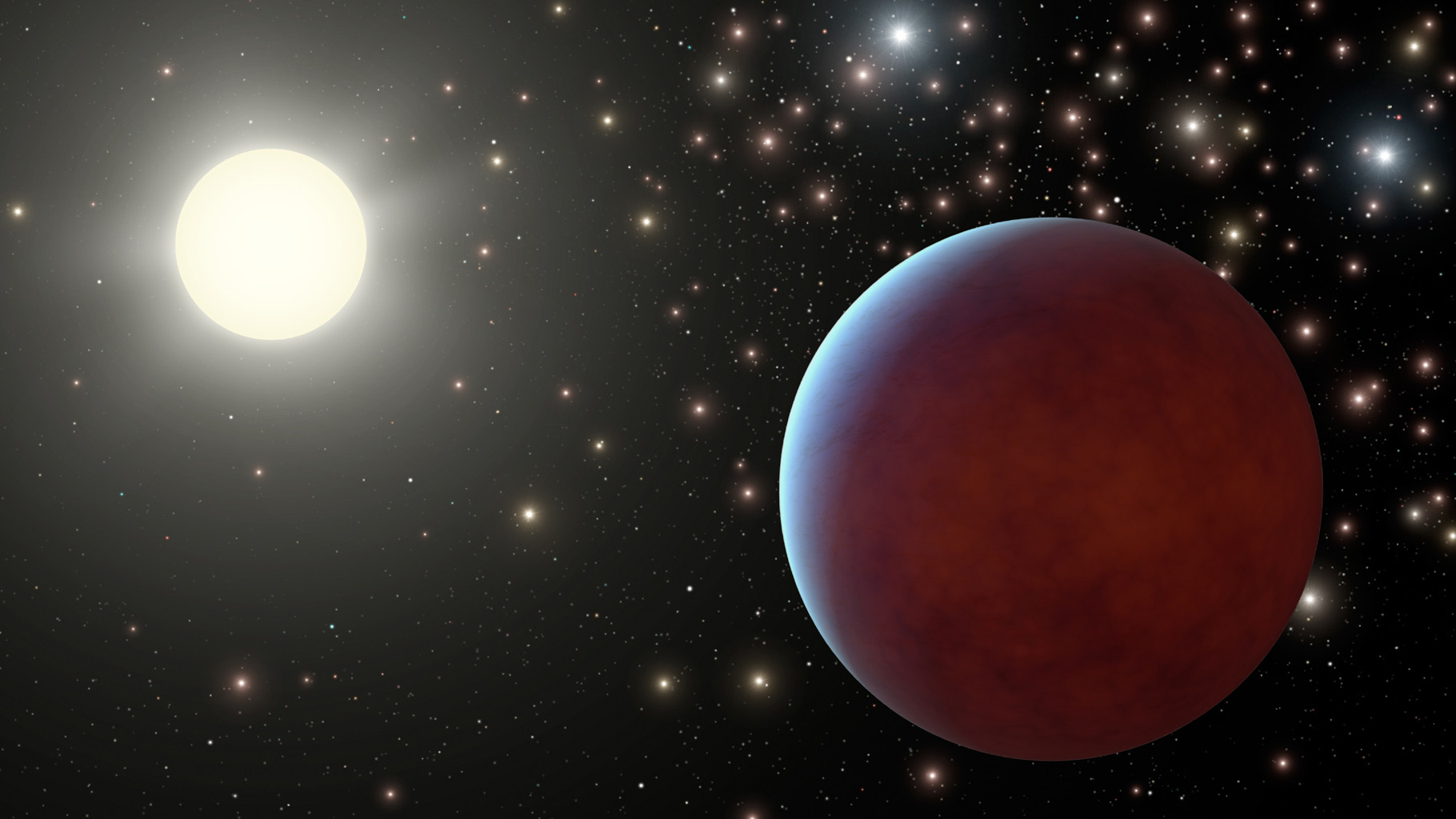

What if scientists could find potentially habitable worlds just by looking at stars?

Looking for life traditionally starts with finding a planet with the right temperature to host liquid water — but scientists are working to find new criteria for tracking down potentially habitable worlds.

One technique could locate promising planets for closer examination based on the chemistry of the host star itself, even before astronomers know anything about a planet directly. That's possible because stellar and planetary compositions are related. And life as we know it requires some very precise chemistry. And while scientists tend to focus on the big-name elements like carbon and oxygen, there are some other, lower-profile flavors that are vital.

Those elements include phosphorus, fluorine and potassium, among others. "They're elements we should care about but haven't yet because we didn't realize we needed to," Natalie Hinkel, a planetary astrophysicist at the Southwest Research Institute in San Antonio, told Space.com.

Related: 7 ways to discover alien planets

Hinkel and her co-author, an oceanographer, presented initial findings from their analyses in January at the 235th meeting of the American Astronomical Society in Honolulu. They focused on phosphorus in particular because the process that turns sunlight into stored energy that organisms from algae to elephants can use requires phosphorus, albeit in small amounts.

"It's like baking a cake: If the cake calls for four eggs and you only have three, then you don't get a cake," Hinkel said. "But in this cake of life, phosphorus is really hard [to find] — so like getting those eggs." So if you're looking for Earth-like life, the scientists figured, find stars with a hint of phosphorus in them and study planets in those systems first.

There's just one little problem: Phosphorus is hard to measure in stars because of a fluke that puts its signature in a wavelength of light that is difficult to observe from Earth or using existing space-based instruments.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

That's why, when Hinkel turned to a database where she gathers observations of stellar chemistry, just 90 stars included measurements of phosphorus amounts, out of more than 6,000 stars in the database. (For comparison, some elemental abundances have been observed for 1,400 of those stars.) Only 12 of those stars are known to host planets that could help them understand the nuances of how phosphorus in the star and planet relate.

A similar problem plagues other elements that are biologically important in small quantities, she said. The data shortages mean that Hinkel and her colleague aren't really pointing to this approach as a feasible technique for selecting interesting exoplanets right now. Instead, they're hoping their research will serve as a call to scientists to work on the problem of gathering data about these tricky elements as well as the old favorites.

Not knowing about phosphorus may not be a deal breaker, of course. Extraterrestrial life, if it exists, may not require phosphorus at all. "There could be certain pathways to life that might not need phosphorus specifically, but we know that life exists with phosphorus and we know that we exist, so it makes the most sense, given what we know now," Hinkel said.

But she argued that it could be a much more useful type of observation than previously recognized. And that, she said, makes it worthwhile for astronomers to put more effort into trying to make measurements of phosphorus and other biologically important but difficult-to-measure elements. "They're all hard for a reason, but it doesn't mean we shouldn't go after it," Hinkel said. "If anything, I've learned that we should go after it all the more."

After all, scientists are going to need every observation they can get their hands on if they want to track down potential life in other solar systems. "Habitability is really difficult to figure out," Hinkel said. "It's not like we can go and get a scoop of the planet, so modeling is pretty much all we're going to have for a very long time."

- The biggest alien planet discoveries of 2019

- Another day, another exoplanet, and scientists just can't keep up

- An Earth-size planet in the habitable zone? New NASA discovery is one special world.

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

OFFER: Save at least 56% with our latest magazine deal!

All About Space magazine takes you on an awe-inspiring journey through our solar system and beyond, from the amazing technology and spacecraft that enables humanity to venture into orbit, to the complexities of space science.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.