How a Massive Database on Stars Will Make It Easier to Explore Alien Worlds

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

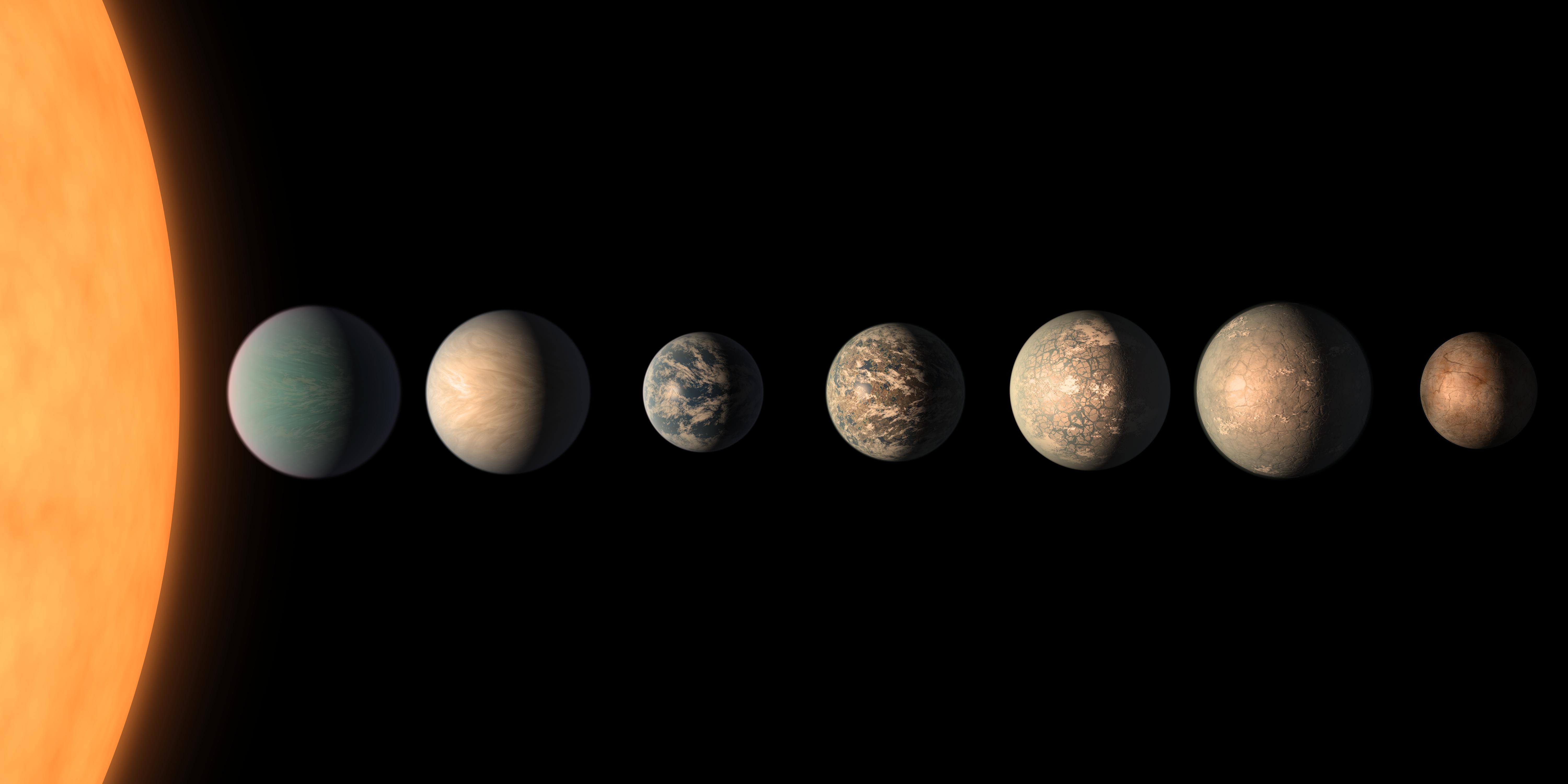

Our sun shapes every day of our lives and always has — and if there's life on alien worlds, the same will be true of their stars.

That means that for scientists hoping to determine whether there's life elsewhere in the universe, it's crucial for them to know more about both exoplanets and the stars they orbit. One such scientist hopes that big data will be able to help her and her colleagues narrow down the most plausible homes of life, and she has built a database to coordinate that effort by pulling together information about the different factors that affect how habitable a planet is.

"At first scientists focused on temperatures, looking for exoplanets in the 'Goldilocks zone' — neither too close, nor too far from the star, where liquid water could exist," Natalie Hinkel, a planetary astrophysicist at the Southwest Research Institute, said in a statement issued by the institute. "But the definition of habitability is evolving beyond liquid water and a cozy temperature."

In particular, scientists have begun to consider a planet's chemical composition, since life as we know it relies on elements like hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, phosphorus, nitrogen, iron and silicon. Scientists don't yet have the technology required to measure planetary composition directly.

But they can measure the ingredient mix of a star and use that as a stand-in for the planet's recipe, another reason why gathering data about stars is just as important as gathering data about planets.

So far, Hinkel's database, which is called the Hypatia Catalog after an ancient Egyptian female mathematician and astronomer, includes composition information for more than 6,000 stars. Of those stars, 365 are already known to host planets. (Scientists estimate that there's an average of at least one planet per star across the galaxy.)

She is also working on developing machine-learning techniques to figure out how stellar and planetary compositions may affect each other.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Email Meghan Bartels at mbartels@space.com or follow her @meghanbartels. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Meghan is a senior writer at Space.com and has more than five years' experience as a science journalist based in New York City. She joined Space.com in July 2018, with previous writing published in outlets including Newsweek and Audubon. Meghan earned an MA in science journalism from New York University and a BA in classics from Georgetown University, and in her free time she enjoys reading and visiting museums. Follow her on Twitter at @meghanbartels.