Pieces of Heaven: A Brief History of Sample-Return Missions

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

CAPE CANAVERAL, Fla. — NASA is about to launch its first-ever asteroid-sampling spacecraft, but the mission won't be the first to bring pieces of another world back to Earth.

The agency's OSIRIS-REx spacecraft is scheduled to lift off from Cape Canaveral Air Force Station here at 7:05 p.m. EDT (2305 GMT) Thursday (Sept. 8). If all goes according to plan, the probe will collect dirt and gravel from a carbon-rich asteroid named Bennu in 2020, then send the material to Earth in September 2023.

You can watch a webcast of OSIRIS-REx launch here , courtesy of NASA TV, beginning at 4:30 p.m. EDT (2030 GMT). The $800 million mission's main goal is to determine the role Bennu-like asteroids may have played in the rise of life on Earth (by perhaps delivering organic molecules and water to the planet). But OSIRIS-REx may enable many more questions to be answered, because researchers in laboratories around the world will study portions of the returned sample for decades, mission team members said. [OSIRIS-REx: NASA's Asteroid Mission in Pictures]

Article continues below"People not yet born, with ideas that we didn't have now, can test them in ways that we couldn't even conceive of," OSIRIS-REx project scientist Jason Dworkin, of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said during a news conference Tuesday (Sept. 6).

Indeed, scientists are still gleaning new insights about the moon from the more than 800 lbs. (360 kilograms) of lunar rock brought back to Earth by the Apollo astronauts in the late 1960s and early 1970s. For example, recent research has shown that these rocks contain a surprising amount of water, forcing scientists to rethink their ideas about the moon's early days.

Apollo marked the first successful return of samples from a world beyond Earth. Shortly thereafter, the Soviet Union's Luna program brought home moon material as well, though in much smaller amounts — about 12 ounces (340 grams) over the course of three robotic missions from 1970 through 1976.

Space-based sample-return then took a 20-year hiatus, coming back in the mid-1990s with an experiment on Russia's Mir space station that collected particles in low-Earth orbit using aerogel.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In 1999, NASA launched the robotic Stardust spacecraft, which grabbed tiny pieces of Comet Wild 2 in January 2004 and delivered this sample to Earth in 2006. (OSIRIS-REx is using the same type of return capsule that Stardust employed.)

And the space agency was operating another robotic sample-return mission at around the same time — Genesis, which lifted off in 2001 and came home to Earth in 2004 with pieces of the solar wind, the stream of charged particles that flow from the sun.

Japan has been a major player in the sample-return sphere as well. The nation launched its Hayabusa probe in 2003 to collect material from a space rock called Itokawa. Things didn't go entirely as planned, but Hayabusa did succeed in getting some tiny Itokawa grains to Earth in 2010.

In December 2014, Japan launched Hayabusa 2, which is scheduled to arrive at the space rock Ryugu in 2018 and return samples in 2020. (Ryugu, incidentally, was one of five asteroids on the OSIRIS-REx team's target short list.)

The next focus for sample return appears to be Mars. In 2020, both NASA and the European Space Agency will launch life-hunting, sample-caching rovers toward the Red Planet. There are currently no firm plans to get this Mars material back to Earth, but NASA has said it intends to do so. Searching for definitive signs of alien life is such a tricky proposition that it should not be left to robots operating solo on a distant planet, agency officials have said.

One sample-return spacecraft has already launched toward Mars: In November 2011, Russia's Fobos-Grunt probe lifted off on a mission to grab material from the Martian moon Phobos. However, Fobos-Grunt suffered an anomaly during launch and never made it out of Earth orbit.

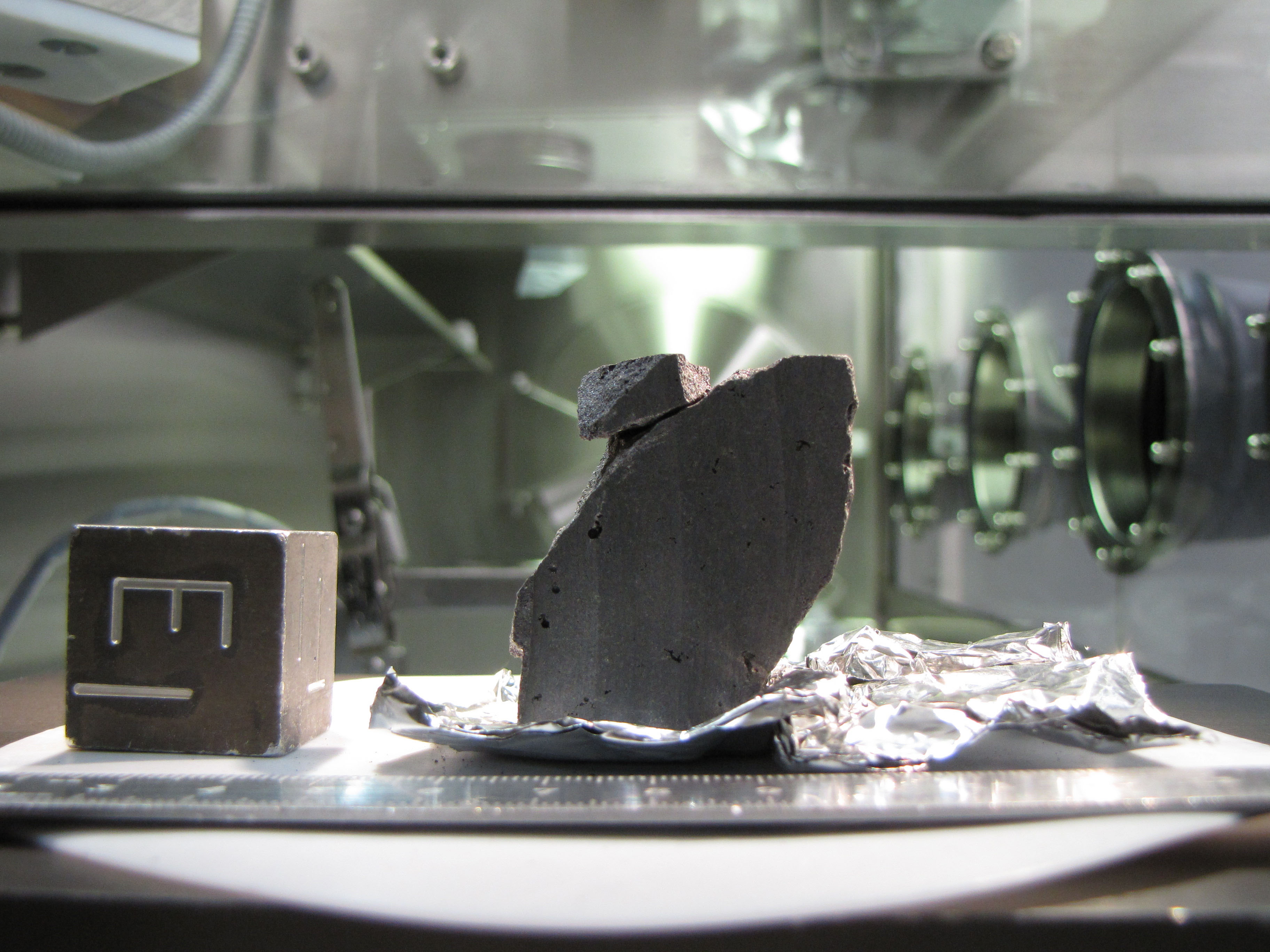

It should be noted that scientists have been able to study pieces of asteroids, Mars and other celestial bodies for decades, in the form of meteorites that have fallen to Earth. However, such manna from heaven is far from pure, said OSIRIS-REx (Origins, Spectral Interpretation, Resource Identification, Security, Regolith Explorer) principal investigator Dante Lauretta, of the University of Arizona's Lunar and Planetary Laboratory.

"A lot of our analyses are confused by the fact that meteorites, once they're on the surface of the Earth, are very quickly contaminated, organically especially, because microbes love these materials," he said during Tuesday's news conference.

"We're really interested in, what [was that] original inventory of material — the seeds of life that these carbon-rich asteroids and comets may have brought to the surface," Lauretta added, explaining why it's so important to grab a pristine sample from Bennu.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.