Space Verdict

The Hesta is not a telescope, at least not in the conventional sense, and on its own it's not a smart instrument, either — it contains no computer and no moving parts. Basically, when coupled with a smartphone, it becomes a kind of low-cost smart telescope, capable of limited night-sky imaging. No batteries or power packs are required, either, which makes the Hestia really simple to use.

Pros

- +

Less expensive than a smart telescope

- +

Portable

- +

Turns your smartphone into a smart telescope

Cons

- -

Small aperture

- -

Limited range of objects that it can image well

- -

Can be fiddly to line up your phone's camera

Why you can trust Space.com

Smart telescopes are great, but they are expensive. Even the least expensive, such as ZWO's SeeStar S30, will set you back in the region of $400. Yet most of us already have a smart device in our pockets. If we could just mate our smartphones to some kind of telescopic device, could we not have our own DIY smart telescope?

That's the ethos behind Vaonis's Hestia. It's not a smart telescope, or even a normal telescope. Think of it as a lens to which you can attach your smartphone and, by using an app on your phone and your phone's built-in camera, you can take images of the night sky. We call this afocal photography; it can be achieved, to an extent, by using an inexpensive smartphone adaptor that holds your phone's camera up to a telescope eyepiece. However, with the addition of Vaonis' Gravity app, the Hestia has a much wider range of guidance, exposure settings, stacking and catalogues of varied objects to choose from.

In short, it's more sophisticated than simply holding your phone up to a telescope eyepiece, but simpler than a smart telescope. The question is, how does it compare?

Vaonis Hestia review

Vaonis Hestia: Design

- Feels solid, not flimsy, unlike the tripod

- Lightweight and portable

- Can be adjusted to fit all models of smartphones

The Hestia comes in a nicely padded protective case, and is about the size of a hardback book, though not nearly as heavy. It comes with a tripod sporting a pan-and-tilt handle so that you can manually move the Hestia around the night sky. The Hestia's mostly white finish is of similar quality to the plastic housing of Vaonis' smart telescopes, such as the Vespera II.

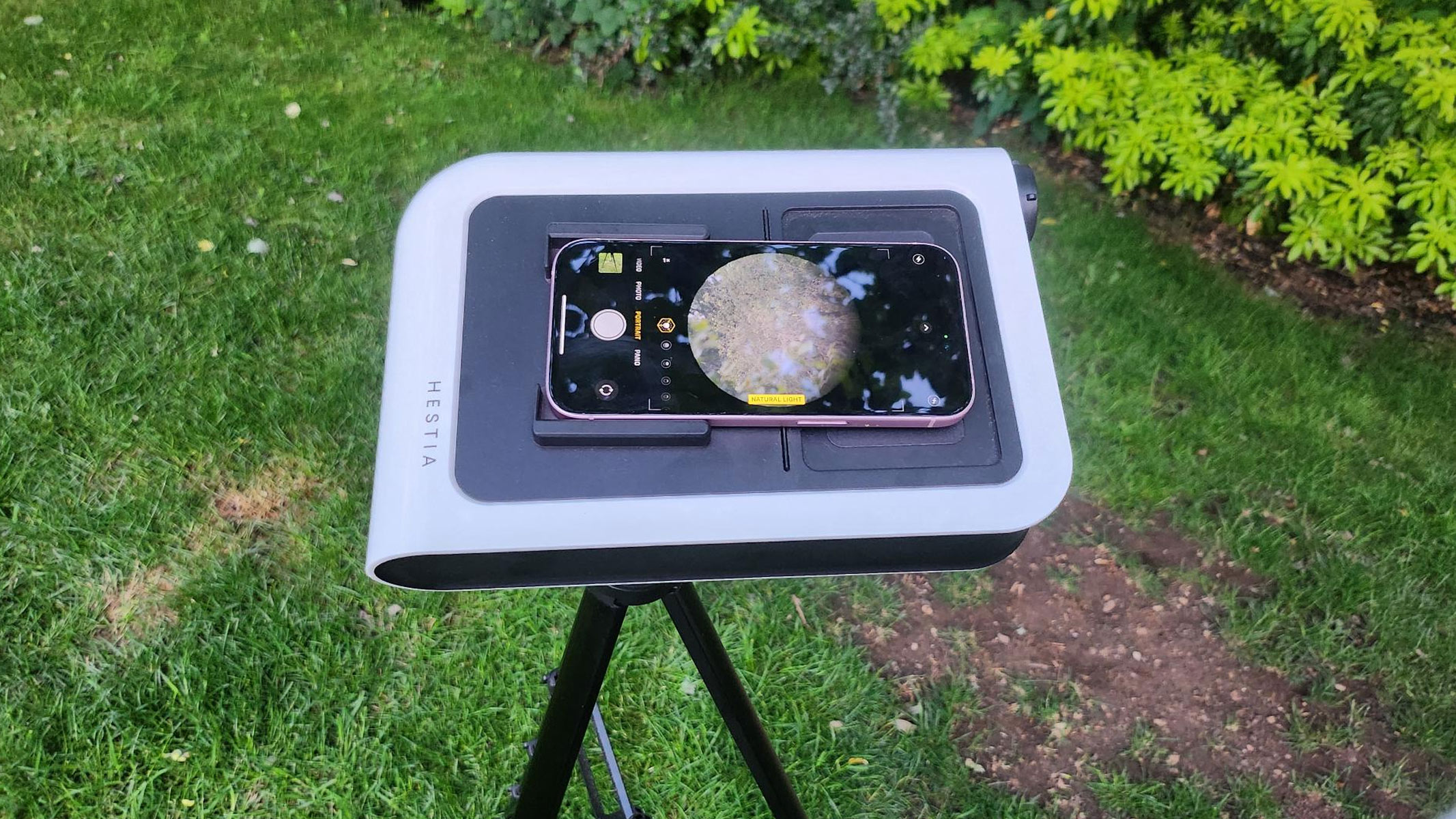

One side of the Hestia is a black metal plate with magnetic clasps that can be moved around and adjusted to fit your choice of phone, and then all you need to do is position your camera over the small opening where the Hestia focuses the light.

Weight: 1.87 lbs (850 g)

Size: 6.7 x 9.5 x 2.2-inches (170 x 240 x 55 mm)

Aperture: 1.2-inches (30 mm)

Magnification: 25x

Field of view: 1.8 degrees

Suitable for: Moon, Sun, stars, brightest deep-sky objects

None of Vaonis' telescopes are particularly aesthetically eye-catching, and the Hestia is probably the ugliest of the lot, with the rubber 'camera-cup', safety warning text and the unappealing black metal plate. If you want an astronomical instrument that looks good, then the Hestia certainly does not match up to a classic refractor. Although its utilitarian appearance suits its economical design, ultimately, it is not about how it looks, but what it can do.

Vaonis Hestia: Performance

- Perfect for imaging the Sun (with solar filter) and the Moon

- Gravity app allows you to stack images

- Lack of motorised tracking is a big limitation

Ordinarily, an aperture just 1.2-inches (30mm) in diameter would be far too small for any half-serious astronomical observing, but most smart telescopes have a small aperture. The Hestia has the same size aperture as the SeeStar S30, for example. The small apertures in these devices are mitigated somewhat by the fact that they are 100% focused on imaging, not visual use, and imaging collects photons and integrates over exposures, building up a picture — something the human eye cannot do, of course. Nevertheless, the limited aperture does constrain the resolution, and the low magnification means that other than the Sun and the Moon, nothing really fills the field of view.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

It is possible, via the Gravity app, to stack individual images together to improve the signal-to-noise ratio and help the faint details stand out. However, this still runs into the problem of having to manually track your target while keeping it aligned in the field of view.

The lack of tracking is also a serious limitation. Again, it's fine for the Sun and the Moon, which are both bright and only need short exposures anyway. It is also okay for stars and star clusters, since you only need a short exposure to see them. For nebulae and galaxies, however, where many integrations over long exposures are required to tease out their faint light, the Hestia is not really suitable. For example, the SeeStar S30 can track the Orion Nebula for half an hour and build up a wonderful image, but after only 30 seconds, all you can see at that point is a faint smudge. Those 30 seconds are really all you get with the Hestia. I did try manually tracking, but it is difficult to keep your target perfectly aligned each time.

Vaonis Hestia: Functionality

- Very simple to use

- The Gravity app is user-friendly

- No motorized tracking

The Hestia will never run out of power because it does not require a battery or any external power. This gives it a significant leg-up over smart telescopes, which have a battery life of between 4 and 8 hours, depending upon the model and weather conditions (cold weather drains batteries faster). All I needed to remember was to keep my phone charged!

I found that getting my smartphone's camera to line up with the rubber cup wasn't as easy as it might at first seem. The two magnetic brackets are quite loose, slipping and sliding across the metal plate. Although they are meant to be that way, and for good reason, as if they held on with too much magnetic strength, they would be difficult to adjust. It does mean that lining up your phone's camera is finicky business, and if you don't take due care, the phone can be nudged out of position. Even if it is just a slight nudge, it means light will fall on a different part of your camera sensor, resulting in a double image.

The accompanying tripod is not the sturdiest, with quite thin lower legs, but the Hestia is not heavy, so as long as you position it on firm ground and are careful not to knock into it, then it should be okay.

The Hestia does not have a tracking mount or any machinery, motorized or otherwise. The focal length and f/ratio are not provided, but the magnification is 25x through a small 1.2-inch (30mm) aperture. But given that it is not motorized it means that it cannot track objects in the sky. This limits exposures of deep-sky objects to about 30 seconds before they start to visibly trail. You could try and manually track objects, using Vaonis's Gravity app as a guide and taking care to center the object each time, but again, a misalignment could lead to a double exposure.

The Hestia comes with a solar filter that I could screw in over the aperture. Users must ensure that the solar filter is attached before pointing the Hestia at the Sun — the intense bright sunlight could otherwise damage the Hestia's optics, your phone's camera and even your eyes if you looked directly through the rubber eyecup at it. There is a warning next to the rubber eyecup reminding you not to do this.

To take images, I had to download Vaonis' free Gravity app from the App Store (or Google Play if you have an Android device). It first asked me to register my Hestia by scanning the QR code on the reverse of the instrument (it's hidden by the tripod head, which I had to unscrew to get to the QR code). Then the app guides you through the positioning of your phone so that it is receiving focused light (focus is achievable with a slider in the app) through the camera. Gravity has three observing modes — Sun, Moon and 'Catalog', which has everything from stars and galaxies to nebulae and planets. I found the Gravity app very easy to use.

Should you buy the Vaonis Hestia?

✅ You're a beginner wanting to image the Moon and the Sun.

✅ You're an eclipse chaser: The Hestia with the solar filter is perfect for imaging solar eclipses.

❌ You're a dedicated astrophotographer: The Hestia is really designed for beginners and those wanting to have a go at imaging the night sky in the easiest way.

❌ You want to image deep-sky objects: The Hestia is not capable of capturing good images of deep-space objects.

The Hestia works surprisingly well for imaging the Sun and the Moon. It is well suited to watching sunspot groups, spying large prominences and tracking the changing phases of the Moon. It also works well for stars and star clusters, but beyond that it is not suitable for deep sky imaging. If a user wishes to image a galaxy or a nebula, their best choice is to get a smart telescope.

If you are not too concerned about taking images then I would argue that a good pair of large binoculars (anything bigger than 10x50s) or a medium-aperture telescope of 5- or 6-inches provides a better view of the Moon, the stars and definitely the planets than the Hestia does. Because of its wide field of view and low magnification, the planets do not look like anything more than bright lights, but this is a common failing of all smart telescopes with their small apertures and wide fields. I could not see the belts of Jupiter or the rings of Saturn, for example.

User reviews of the Vaonis Hestia

Reviewers on amazon.com were broadly supportive of the Hestia, highlighting its portability, the functionality of the Gravity app and its appeal to users who want to try out astrophotography but who don't have the skills, money or time to purchase dedicated large imaging cameras and telescopes. On the negative side of things, some users found focusing to be difficult and lamented the lack of motorized finding and tracking.

If the Vaonis Hestia isn't for you

There isn't really an instrument quite like this on the market, but if you are interested in low-cost afocal photography and already own a telescope, I suggest just buying a smartphone adaptor that can attach to the eyepiece.

If you are looking for something more sophisticated, then try Vaonis' range of smart telescopes, in particular the Vespera II or the Vespera Pro.

Gemma currently works for the European Space Agency on content, communications and outreach, and was formerly the content director of Space.com, Live Science, science and space magazines How It Works and All About Space, history magazines All About History and History of War as well as Science, Technology, Engineering, Arts and Mathematics (STEAM) kids education brand Future Genius. She is the author of several books including "Quantum Physics in Minutes", "Haynes Owners’ Workshop Manual to the Large Hadron Collider" and "Haynes Owners’ Workshop Manual to the Milky Way". She holds a degree in physical sciences, a Master’s in astrophysics and a PhD in computational astrophysics. She was elected as a fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society in 2011. Previously, she worked for Nature's journal, Scientific Reports, and created scientific industry reports for the Institute of Physics and the British Antarctic Survey. She has covered stories and features for publications such as Physics World, Astronomy Now and Astrobiology Magazine.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.