NASA's Ailing Kepler Spacecraft Could Hunt Alien Planets Once More with New Mission

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

NASA's hobbled Kepler space telescope may be able to detect alien planets again, thanks to some creative troubleshooting.

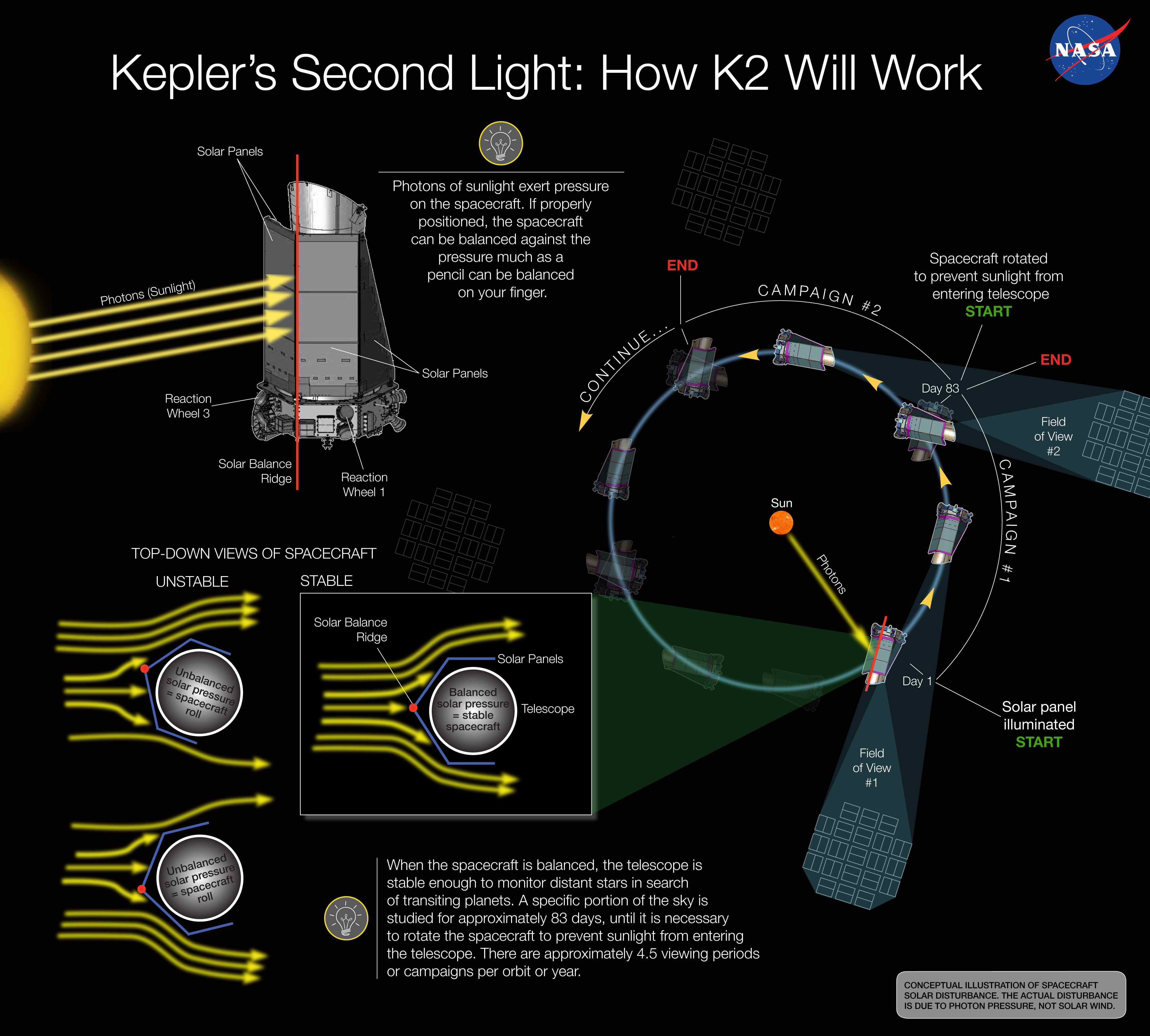

Kepler's original planet hunt ended this past May when the second of its four orientation-maintaining reaction wheels failed, robbing the spacecraft of its ultraprecise pointing ability. But mission team members may have found a way to restore much of this lost capacity, suggesting that a proposed new mission called K2 could be doable for Kepler.

Engineers with the Kepler mission and Ball Aerospace, which built the telescope, have oriented the spacecraft such that it's nearly parallel to its path around the sun. In this position, the pressure exerted by sunlight is spread evenly across Kepler's surfaces, minimizing drift. [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

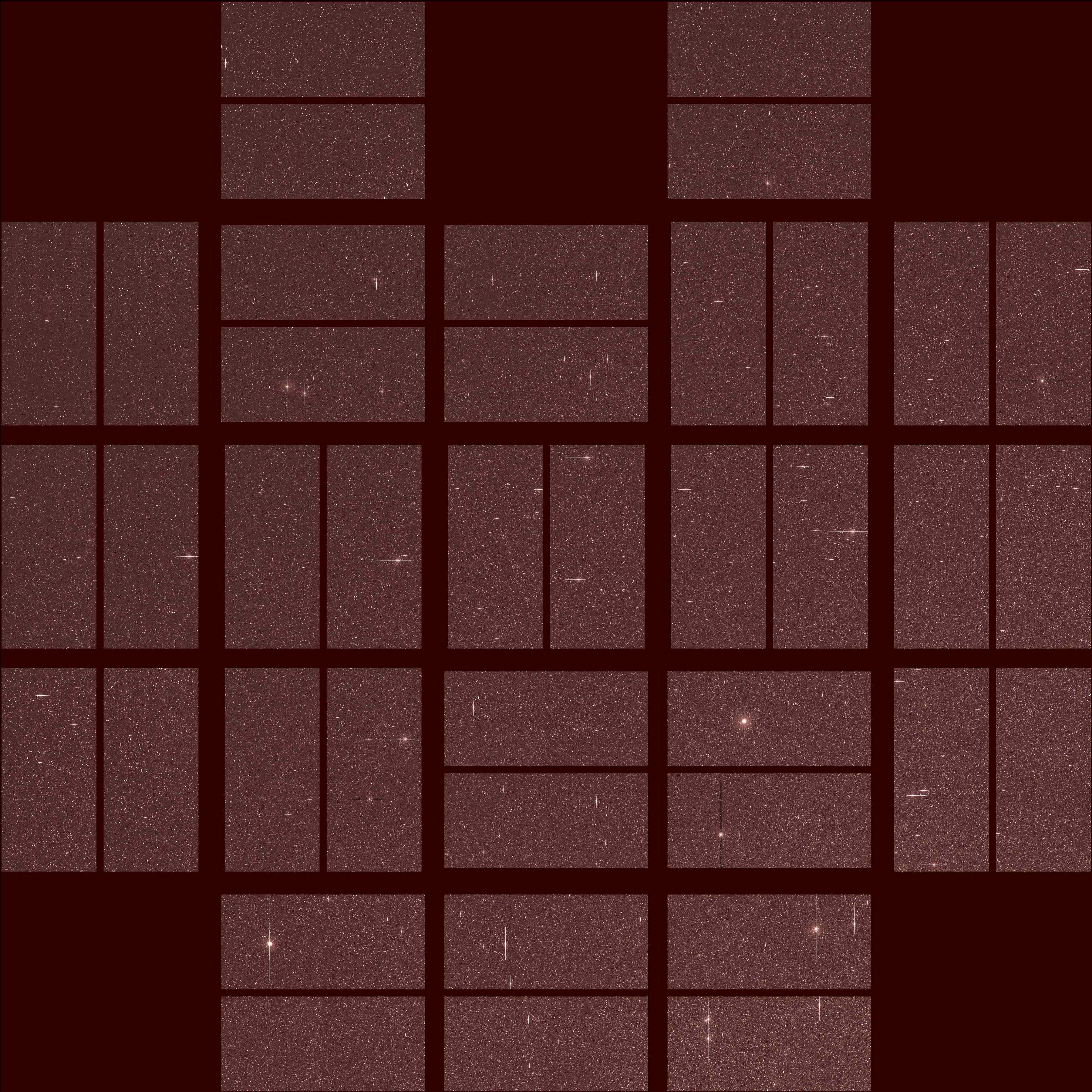

This strategy is returning some promising results, mission officials say. During a 30-minute pointing test in late October, for example, Kepler captured an image of a distant star field that was within 5 percent of the image quality achieved during Kepler's original mission.

"This 'second light' image provides a successful first step in a process that may yet result in new observations and continued discoveries from the Kepler space telescope," Charlie Sobeck, Kepler deputy project manager at NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, Calif., said in a statement.

The Kepler team is currently conducting tests to see if the spacecraft can maintain such pointing stability over periods of days and weeks — a necessity for discovering exoplanets.

Kepler launched in March 2009 on a mission to determine how frequently Earth-like planets occur around the Milky Way galaxy. The spacecraft finds exoplanets via the "transit method," noting the telltale brightness dips caused when an alien world crosses the face of, or transits, its host star from the instrument's perspective.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Kepler has been remarkably successful, spotting more than 3,500 planet candidates to date. Just 167 of them have been confirmed so far by follow-up observations, but mission scientists think 90 percent or so will end up being the real deal.

Researchers are still sifting through the mountains of data Kepler returned during its four years of science operations. Kepler team members have expressed confidence that they'll find Earth analogs in these databases, allowing the mission's primary goal to be achieved.

The Kepler team has officially presented the K2 mission concept to NASA Headquarters, which is expected to decide by the end of the year if the idea progresses to a vetting stage called "senior review." The ultimate fate of K2, and the Kepler spacecraft, will likely be known by the middle of next year, Kepler officials have said.

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on SPACE.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.