What if we've been thinking about dark matter all wrong, scientist wonders

"I think it's natural to take a break and wonder whether we are fundamentally thinking about this in the wrong way."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Dark matter could be made from tiny black holes formed when so-called "dark baryons" collapse, scientists suggest. Or, alternatively, dark matter could be a type of particle created by a form of Hawking radiation on the cosmic horizon.

Here's what all that means.

Dark matter is the substance that appears to make up about 27% of our universe, compared to the 5% of our universe composed of "normal" matter. Scientists certainly know dark matter exists due to some peculiar effects observed in the cosmos that normal matter can't account for. However, nobody knows what dark matter is made of.

For decades, the leading candidate has been WIMPs, or Weakly Interacting Massive Particles. But as the search for WIMPs begins to falter with experiments continuing to turn up empty handed, new theories of dark matter are starting to surface. Among them are two new models developed by Stefano Profumo, who is a professor of theoretical physics at the University of California, San Diego — and his ideas take a very different view of the dark-matter problem.

"My attitude is that we've tried very hard to think about dark matter as a particle, but it hasn't worked out so far," Profumo told Space.com. "I think it's natural to take a break and look at the whole thing from a distance, and wonder whether we are fundamentally thinking about this in the wrong way."

In one paper, Profumo considers whether the "dark sector" could be what gives birth to dark matter. By dark sector, he isn't referring to how our universe is governed by dark matter and dark energy. Instead, he's referring to a kind of "mirror world" of particles that interact via forces that our world's kind of matter does not experience.

Profumo says the concept is not as strange as it may sound. For example, he highlights how the quarks inside protons and neutrons are bound together by the strong nuclear force.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"But then take electrons, which are absolutely blind to the strong force. They don't feel it at all. For them the strong force is a dark sector," said Profumo. "It's common in the Standard Model."

Dark baryons would be the equivalent of protons or neutrons in this dark sector, except that they could contain more than three quarks, Profumo says, and therefore be more massive.

The next step in the researcher's theory was inspired by his teenage son asking whether a sufficiently massive particle could collapse under its own gravity to form a mini black hole. The dark baryons in the dark sector, if it so exists, could be massive enough to do just that — and these tiny black holes could then be rife in the universe and collectively form what we call dark matter.

"I've worked with people who have thought very deeply about a dark-sector equivalent to the strong force, but they've never really pushed all the way to the black hole frontier," said Profumo. "But I really think it is a possibility that we need to take into consideration."

Black holes, large or small, are surrounded by an invisible boundary called the event horizon, inside which gravity is so strong that not even light can escape. However, the event horizon is 'hot' – particles created at the boundary by quantum effects can radiate away as what we call Hawking radiation (named for famous physicist Stephen Hawking, who is credited with the idea). Over time, Hawking radiation removes mass and energy from a black hole, causing it to gradually evaporate. For supermassive black holes, this would take an unimaginably long time — 10^100 years at least. However, black holes on the smallest scales — what we call the Planck scale —- can evaporate in an amount of time less than the age of the universe.

However, if we make certain assumptions about the nature of these black holes formed by the collapse of dark baryons, then their Hawking radiation could become suppressed, preventing them from evaporating and enabling them to act as dark matter.

Meanwhile, Profumo's other idea plays on the concept of Hawking radiation as well, but in a completely novel way.

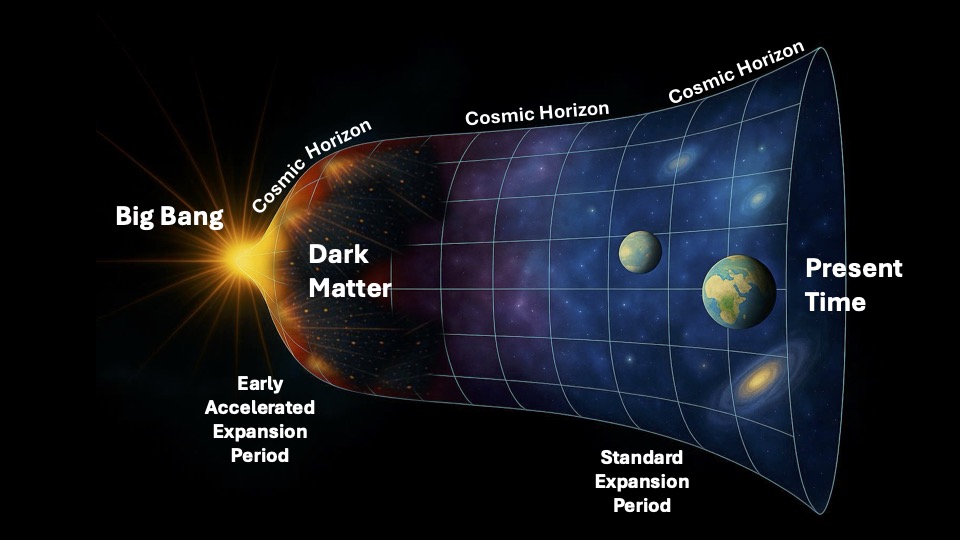

We live in a universe that is expanding at an accelerating rate, taking regions of the cosmos so far away that their light will never reach us. This leads to a boundary, or a cosmic horizon, which defines the edge of the visible universe. There could be much more of the universe beyond this horizon, but we will never see it.

Now, let's go back in time to the moment of the Big Bang. The universe began with a burst of expansionist energy known as inflation. This inflationary period lasted a tiny fraction of a second. However, some models also posit that there was a second brief burst of expansionary energy that followed inflation.

"It is basically a period of mini-inflation," said Profumo. "It could be associated with inflation and how it ends, or it could be driven by a similar set-up to inflation."

This second expansionary period created cosmic horizons like the cosmic horizon that borders the visible universe today. However, the visible universe today is 93 billion light-years across, with Earth at its center (the concept of a "visible" universe is very observer dependent — observers in different parts of the cosmos will see a different volume of observable universe centered around themselves). The vast size of the visible universe means the temperature at the cosmic horizon is very low because space itself has become so spread out.

However, during the second burst of inflation, the universe was still incredibly compact and the temperature at the horizon was extremely hot.

Profumo realized these early cosmic horizons could act like event horizons; indeed, the concept is a bit like a black hole but turned inside-out because everything beyond the cosmic horizon is forever disconnected from us, just like everything inside a black hole's event horizon is separated from us. And just as Hawking radiation is emitted from a black hole's event horizon, Profumo suggests the cosmic horizon could also experience Hawking radiation in the same manner, and that the energy of this radiation could transform into some kind of dark matter particle.

"Maybe [dark matter] is as simple as that," said Profumo. "Early on, the universe behaved like a black hole, and there was stuff sprinkled into the universe because the universe was evaporating in the same way that a black hole evaporates."

This might seem somewhat arbitrary, because the location of the cosmic horizon depends upon the location of the observer. However, because the universe is homogenous (the same at every point on large scales) and isotropic (the same in all directions) — two truisms that we call the Cosmological Principle —- then any two observers should see the exact same amount of dark matter, wherever they are.

Profumo isn't necessarily saying dark matter has to be one of these two possibilities; indeed, the fact that he has developed two theories implies that he's reluctant to nail his colors to any particular mast.

"The aim of the game is to understand the breadth and scope of what dark matter could be, and to cast the net as wide as possible," said Profumo.

All we know for sure about dark matter is that it interacts via gravity, and yet despite its mystery it is utterly dominant in how matter in the universe assembles itself into galaxies. Almost a century since Fritz Zwicky first suggested the existence of dark matter, and about half a century since Vera Rubin confirmed the need for dark matter in our universe, we still don't know anything more about it. Experiments can narrow down dark matter's properties, so the more ideas we have on the table, the more likely it is that we will be able to match one of them up to the observed properties of dark matter.

Profumo's dark sector–black hole hypothesis was published on May 9 in Physical Review D, and his cosmic horizon model was published in the same journal on July 8.

Keith Cooper is a freelance science journalist and editor in the United Kingdom, and has a degree in physics and astrophysics from the University of Manchester. He's the author of "The Contact Paradox: Challenging Our Assumptions in the Search for Extraterrestrial Intelligence" (Bloomsbury Sigma, 2020) and has written articles on astronomy, space, physics and astrobiology for a multitude of magazines and websites.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.