Commercial Space Race Revolutionizing Business Off Planet Earth

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

LONDON — For decades, the space race was seen as being mostly about national pride. Getting there first mattered most, whereas pushing the frontiers of science and technology took a close second.

The first man in space, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin, was proclaimed by the Kremlin as Citizen of the World and hailed as a sign of communist leadership. Watching NASA astronaut Neil Armstrong set foot on the moon made Americans grin in triumph and forced Soviet leaders to grit their teeth.

Even today, national pride may be fueling space launches, for instance, in places like China and India, both emerging players in the space game, according to space industry experts at a Nov. 20 summit here. On Nov. 5, India’s national space agency, the Indian Space Research Organization, launched a spacecraft dubbed Mangalyaan to Mars. China, which a decade ago became the third nation to send its own astronauts into orbit, is currently building a lunar rover and a space station, while also planning its own unmanned mission to Mars. [See photos from India's first Mars mission]

Article continues belowNot everybody believes this kind of space race, or one between countries, is delivering real value. "Going to the moon didn't bring a lot of commercial value to the U.S. It was just a great pride for the nation," said Mohammad Riaz Suddle of the National Space Agency of Pakistan.

Going to the moon "might not have brought direct commercial value" to the United States, said Chad Anderson, director of European Operations at the Space Angels Network, "but the impact on the economy was huge."

That may be especially true now, as the space race shifts from nations to commercial enterprise. Space offers plenty of business opportunities, at least in the eyes of the space enthusiasts coming to the International Space Commerce 2013 Summit in London, where entrepreneurs, investors and state-sponsored space organizations gathered to discuss ways of making space exploration profitable.

Business beyond Earth

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

When a rocket built by SpaceX, the California-based private spaceflight company, docked with the International Space Station in May 2012, it marked the beginning of this new era of a commercial space race.

SpaceX is not the only commercial player. In fact, the marketplace is rapidly getting crowded. In September, Orbital Sciences of Dulles, Va., became the second private firm to send a spacecraft to the space station; many other firms, among them Virgin Galactic, Blue Origin and XCOR Aerospace, are busy making their own rockets.

But this private industry space race is not just about space transportation. Bigelow Aerospace, based in Los Angeles, for example, is building inflatable space habitats. Planetary Resources and Deep Space Industries meanwhile are hatching plans to mine asteroids for precious metals. [Planetary Resources' Plan to Mine Asteroids (Photos)]

And then there are satellites. Planet Labs, Skybox Imaging and Nanosatisfi, among other small firms, have taken what was once the domain of governments and big corporations into their own hands. This "downstream" business of satellite manufacture is now putting so many satellites into orbit that the problem of space debris is getting more acute than ever – making a disaster depicted by Hollywood’s recent blockbuster “Gravity” ever more likely.

Even students can join the space race. In February the Surrey University Space Center in the United Kingdom blasted a rocket into orbit. Its payload: a smartphone, kitted out to do some basic research.

Generation Orbit (GO), a start-up based in Atlanta, Ga., is run by just a handful of young entrepreneurs and seasoned aerospace veterans. Launched just two years ago, the firm specializes in providing dedicated launch services to the emerging market for tiny nanosatellite.

GO recently secured the $2.1 million sale of the maiden flight of GOLauncher 2, the company's nanosatellite launch vehicle; it will launch NASA's three 3U CubeSats to a 264-mile-high (425 km) orbit as part of the NASA Enabling eXploration and Technology (NEXT) contract. The company is currently developing GOLauncher 2 in preparation for its initial operations in 2016.

The firm has also won $100,000 in prize money from NASA in the NewSpace Business Plan competition in Stanford. According to GO chief operating officer AJ Piplica, the start-uphas "clients lined up" to send their satellites into orbit. These satellites will do a variety of things, he said, such as high altitude science, microgravity research, and hypersonic flight-testing.

Space cheeseburgers

Such cosmic entrepreneurial spirit shouldn't stop at private launches, said Rick Tumlinson of Deep Space Industries.

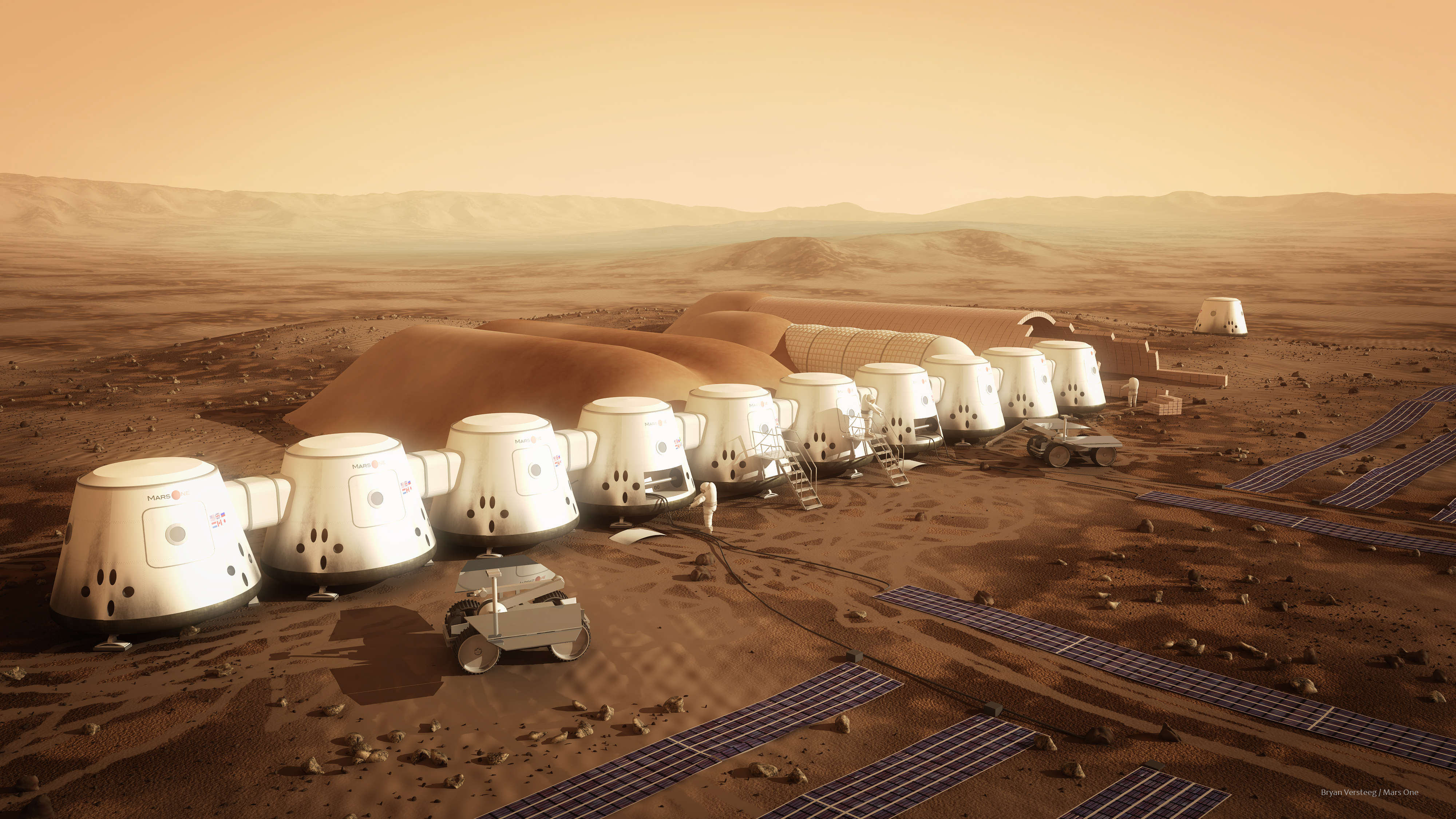

"When people go to Mars, I want to be able to sell them air, water and cheeseburgers," Tumlinson joked, adding that digging precious metals out of asteroids is just one of the opportunities to explore.

"Our planet sits in a vast sea of resources, and we need to learn to harvest them wherever we go. Space rocks contain everything we could ever need. We have to seize the opportunity. Space should be opened and will be opened," he added. [The Boldest Mars Mission in History (Countdown)]

Space is also becoming much more international, with smaller countries not only launching telecommunication satellites, but aiming much higher. Sweden, for instance, has its own spaceport. It hopes to launch commercial human missions and within a decade wants to be Europe's gateway to space. Poland recently joined the European Space Agency and is actively promoting research and collaboration with the private sector – with both Polish and foreign companies.

Regardless of size, nations with big space ambitions can greatly contribute to the future of space development, said Jan Polar, director of the Czech Space Office, a non-governmental agency promoting space research and commerce in the Czech Republic.

In the 1970s, Czechoslovakia gave the world its first mini satellite, Magellan-1. Since then, it has launched just a few more — but such "contributions of smaller nations can help keep [the] program continuity, as it can happen that there are not enough resources in big countries, and even small contributions can be essential to keep a program running," Polar said.

And, he added, that's exactly where the private sector comes into play: "Commercial space activities provide new opportunities for small countries to increase their capabilities and to contribute to exploration — and this can be beneficial in many aspects, such as economic, cultural and social."

Commercialization is also the only way to keep the space sector successful and benefit the Earth, said Gerd Gruppe of the German space agency DLR. As space budgets of governments stagnate, private firms are opening up new markets.

"The young companies are the most successful job motors, they are the ones looking for new employees and investing in the workforce. The frontiers are opened by people and not by governments,” he said. “It’s the right time to strengthen commercialization, and we want more space activity for our money. The space business has to become faster and cheaper, otherwise it won’t be fit for the future.”

Most importantly, said Gruppe, space activities have to enable technologies for other markets, with significant impact.

Regulating space

As more and more rockets lift off, public and private, carrying humans or cargo to the International Space Station or satellites into orbit, the world is in obvious need of a proper framework to regulate the ever-more buzzing space sector.

After all, today's space law dates back to more than four decades ago, when the Outer Space Treaty was signed in 1967. Back then, only governments launched rockets, and the liability of whatever was blasted into orbit lay with the so-called launching state.

Today, Earth is circled by a myriad of privately owned objects; however, if two of them were to collide it is not the company that would be liable for any damage, but the launching state.

"What we're seeing now is the commercialization of the [space] industry, just as with the airline industry a hundred years ago," said Karin Nilsdotter, the head of Spaceport Sweden, which is working closely with Virgin Galactic to send a rocket into orbit.

Sweden has launched many rockets during the past 50 years, but Nilsdotter said the country now wants to become a world-leading space destination for sub-orbital human spaceflight.

"To be able to launch within the next five to 10 years out of Sweden, we are now working on establishing guidelines for manned spaceflight, working together with the operators and also with the FAA in the U.S. to establish a business-friendly framework," Nilsdotter said.

"It's all about enabling a new industry, where we'll be able to attract new talent and new investments, and see the technology transfer into other industries, and transform them. Space is an industry of the future, and we need to be ready to deal with it properly."

Follow Katia Moskvitch on Twitter @SciTech_Cat. Follow us @Spacedotcom. We're also on Facebook and Google+. Original article on SPACE.com.

Katia Moskvitch is a freelance science writer based in Switzerland currently serving as the head of communications for IBM Switzerland. She an award-winning writer who has covered astrophysics and other topics for Space.com, with her work also appearing in Quanta Magazine, Science, Wired, BBC News, Scientific American and The Economist among others.

In 2019, Katia was named European Science Journalist of the Year as well as British Science Journalist of the Year, and her book "Neutron Stars: The Quest to Understand the Zombies of the Cosmos" was published by Harvard University Press in September 2020. Katia holds a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from McGill University and master's degrees in journalism from the University of Western Ontario and in theoretical physics from King's College in London. She is fluent in English, French and Russian.