Asteroids Battered Young Earth Longer Than Thought

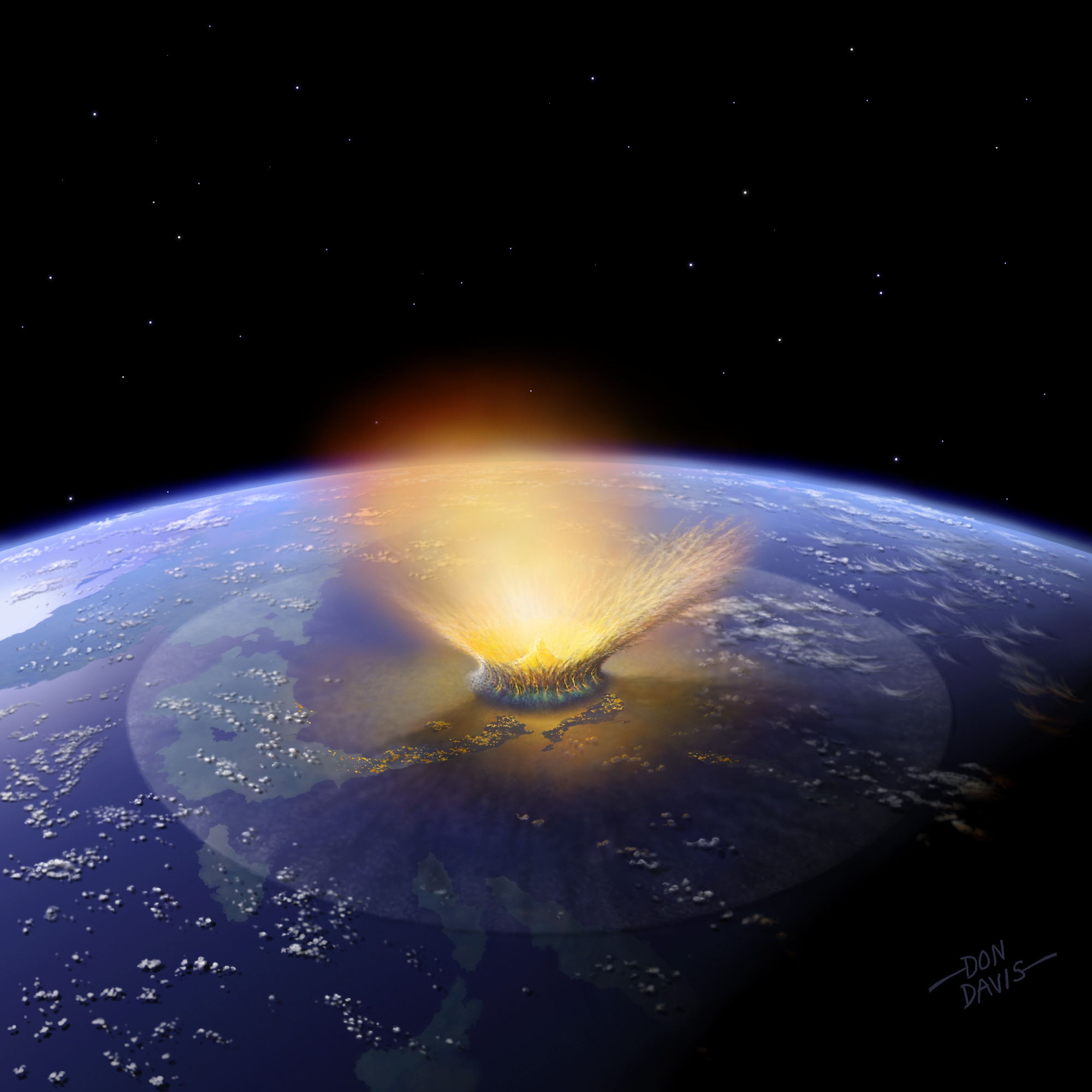

A giant ancient barrage of asteroids striking Earth may have lasted much longer than previously thought, with some collisions perhaps even rivaling those that created the largest craters on the moon, researchers say.

Scientists think untold numbers of asteroids and comets pummeled Earth, the moon and the inner planets during an era known as the Late Heavy Bombardment about 4.1 billion to 3.8 billion years ago. Investigators continue to debate the precise nature of this epoch in terms of what happened and how long it lasted.

To learn more about the Late Heavy Bombardment, scientists would like to analyze the most obvious evidence cosmic impacts leave behind, their craters. However, while such craters are preserved well in the vacuum of the moon environment, they disappear quickly on Earth due to erosion and tectonic activity.

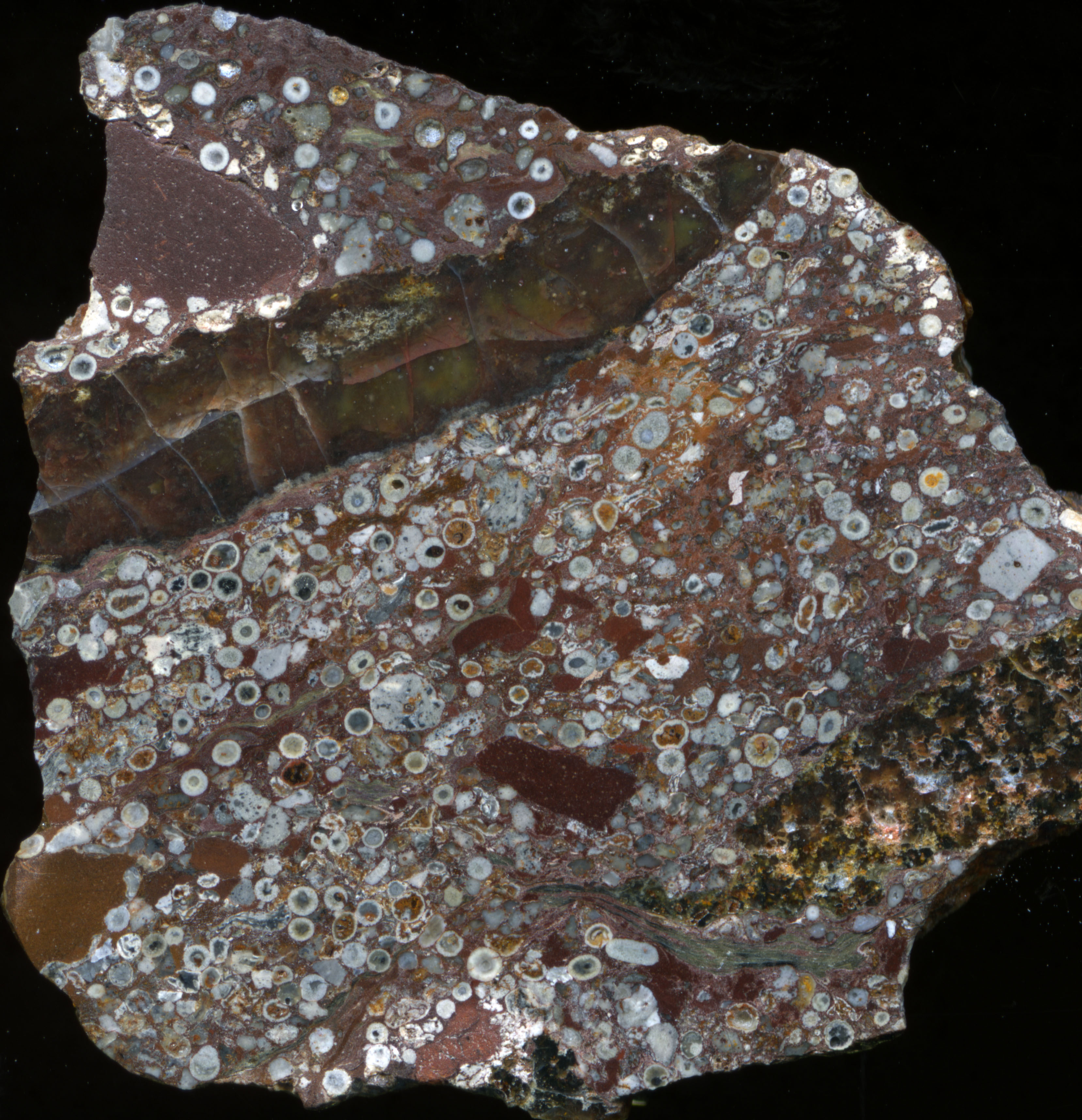

Instead, researchers analyzed other evidence of asteroid impacts — millimeter- to centimeter-thick layers of rock droplets known as spherules.

"Spherule layers, if preserved in the geologic record, provide information about an impact even when the source crater cannot be found," said study lead author Brandon Johnson at Purdue University.

Gigantic collisions kicked up huge molten plumes that rained down beds of sand-sized spherules.

"We can look at these spherules, see how thick the layer is, how big the spherules are, and we can infer the size and velocity of the asteroid," said study co-author Jay Melosh at Purdue University. "We can go back to the earliest era in the history of the Earth and infer the population of asteroids impacting the planet." [Video: Killer Asteroids Explained]

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Modeling Earth's asteroid barrage

The scientists used computer models to deduce impact sizes from spherule bed properties.

"Some of the asteroids that we infer were about 40 kilometers (24.8 miles) in diameter, much larger than the one that killed off the dinosaurs about 65 million years ago that was about 12 to 15 kilometers (7.4 to 9.3 miles)," Melosh said.

"The impacts may have played a large role in the evolutional history of life," Johnson added. "The large number of impacts may have helped simple life by introducing organics and other important materials at a time when life on Earth was just taking hold."

When the researchers looked at the number and sizes of impactors, the pattern they saw suggested many more small objects than large ones, "a pattern that matches exactly the distribution of sizes in the asteroid belt," Melosh said. "For the first time we have a direct connection between the crater size distribution on the ancient Earth and the sizes of asteroids out in space."

At least 12 spherule beds deposited between 1.7 billion and 3.47 billion years ago have been found. This reveals that impacts occurred well after the presumed end of the Late Heavy Bombardment.

"The Late Heavy Bombardment lasted much longer than previously thought — it goes to at least 2.5 billion years ago, although the number of impacts dropped off over time," Johnson told SPACE.com.

Did Jupiter play a role?

The best available model of the Late Heavy Bombardment suggests the giant planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune migrated around the solar system at this time, with their gravitational pulls slinging asteroids and comets toward the inner solar system. However, this model would suggest the Late Heavy Bombardment only lasted 100 million to 200 million years, not nearly long enough to explain the newfound spherule beds. [Fallen Stars: A Gallery of Famous Meteorites]

Instead, William Bottke at the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colo., and his colleagues investigated a possible missing source of impactors along the inner edge of the main asteroid belt. This region, known as the E belt, is now mostly unstable, but researchers think this may not have been the case 4 billion years ago, holding enough matter to barrage Earth with numerous asteroids and comets over a long time.

Specifically, they estimate that approximately 70 dinosaur-killer-size or larger impacts hit the Earth over a span that lasted between 3.8 and 1.8 billion years ago, with four also hitting the moon.

The frequency of these impacts was high enough to reproduce the known spherule beds, and also hints at the possibility that two gigantic craters resulted from the Late Heavy Bombardment — the enormous 112-mile-wide (180-km) Vredefort crater in South Africa, which is 2 billion years old, and the nearly 155-mile (250-km) Sudbury crater in Canada, which is 1.85 billion years old.

"These huge craters may be the last gasp of the Late Heavy Bombardment on Earth," Bottke told SPACE.com.

The very largest impacts on Earth during the Late Heavy Bombardment should be similar to the ones causing the 15 or so youngest and largest lunar basins, some of which are roughly 186 miles wide (300 km). The strikes that gouged out such huge holes may have released nearly 500 times the blast energy of the Chicxulub impact, the one thought to have ended the Age of Dinosaurs, researchers said.

"It will be interesting to see whether these mammoth events affected the evolution of early life on our planet or our biosphere in important ways," Bottke said.

The scientists detailed their findings online April 25 in two papers in the journal Nature.

Follow SPACE.com for the latest in space science and exploration news on Twitter @Spacedotcom and on Facebook.

Charles Q. Choi is a contributing writer for Space.com and Live Science. He covers all things human origins and astronomy as well as physics, animals and general science topics. Charles has a Master of Arts degree from the University of Missouri-Columbia, School of Journalism and a Bachelor of Arts degree from the University of South Florida. Charles has visited every continent on Earth, drinking rancid yak butter tea in Lhasa, snorkeling with sea lions in the Galapagos and even climbing an iceberg in Antarctica. Visit him at http://www.sciwriter.us