Ancient Australian rocks may shed new light on the birth of the moon

"This supports the theory that a planet collided with early Earth and the high-energy impact resulted in the formation of the moon."

Some of Earth's oldest rocks buried deep in Western Australia may hold new clues about the dramatic event that gave rise to our moon.

In a new study led by the University of Western Australia (UWA), researchers analyzed 3.7-billion-year-old feldspar crystals found within magmatic anorthosite rocks from the Murchison region — among the oldest surviving pieces of Earth's crust — to uncover chemical fingerprints from our planet's earliest days. These anorthosites are particularly intriguing because while they're very common on the moon, they are rarely found on Earth, hinting at a deep connection between the two worlds, according to a statement from UWA.

"The timing and rate of early crustal growth on Earth remains contentious due to the scarcity of very ancient rocks," Matilda Boyce, lead author of the study and Ph.D. student at UWA, said in the statement. “We used fine-scale analytical methods to isolate the fresh areas of plagioclase feldspar crystals, which record the isotopic 'fingerprint' of the ancient mantle."

Anorthosite rocks formed when molten magma slowly cooled deep beneath the surface, allowing large plagioclase feldspar crystals to grow and lock in chemical clues about the environment in which they formed. Because these ancient rocks have remained remarkably intact for billions of years, isotopic dating reveals when the minerals solidified, unlocking a direct glimpse into Earth's earliest crust and our planet’s infancy.

Using this method, the team was able to measure isotopic ratios that reveal what Earth's mantle and crust looked like billions of years ago. Their results suggest that continental growth didn’t begin immediately after the planet formed, but rather started later, around 3.5 billion years ago — nearly a billion years after Earth's birth.

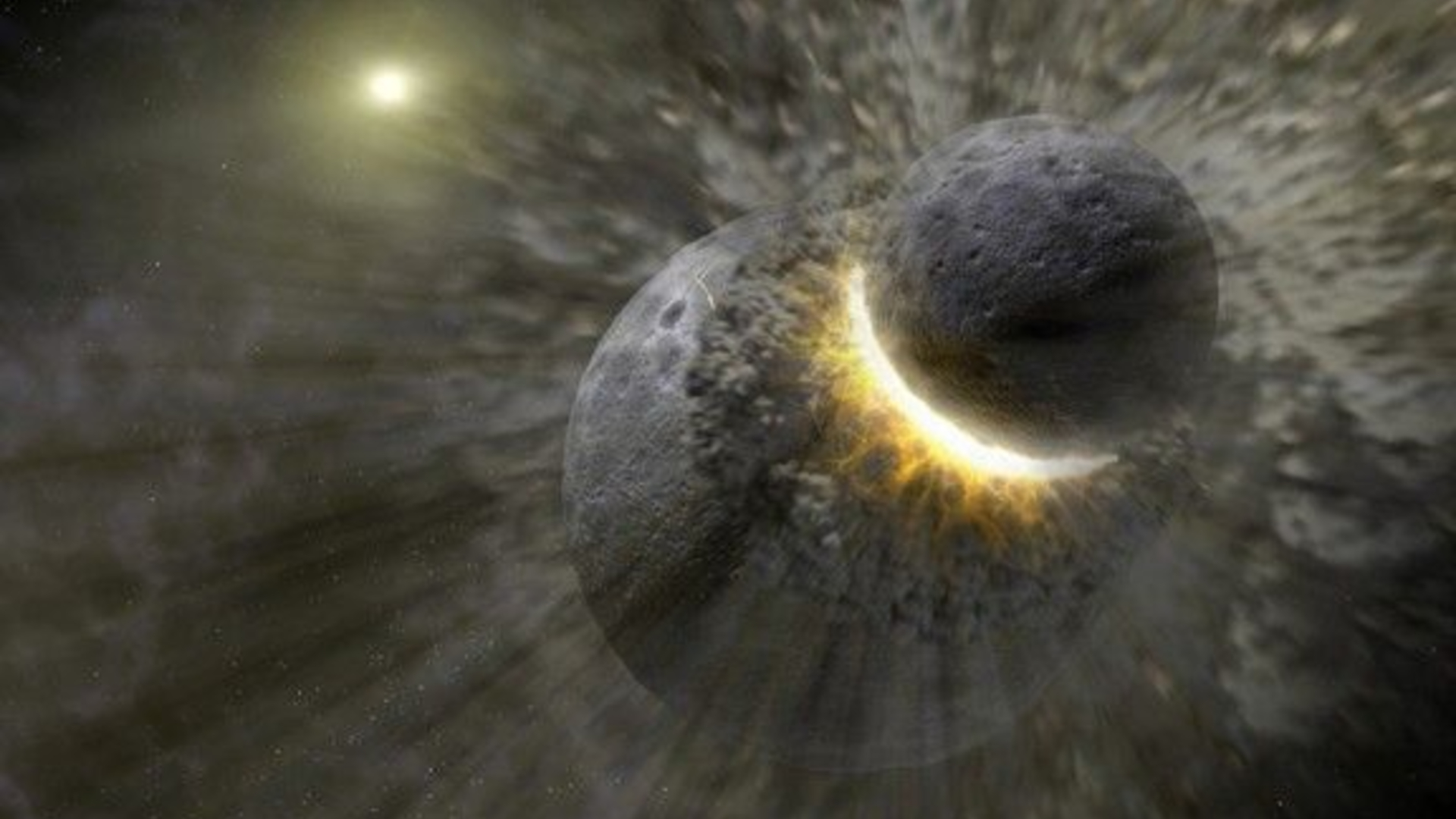

Even more striking, the researchers found that the isotopic signatures from the Australian rocks closely resemble those found in lunar samples collected during NASA's Apollo missions. That chemical link supports the leading "giant impact" theory for the moon's formation, in which a Mars-size object slammed into early Earth about 4.5 billion years ago, ejecting material that eventually coalesced into the moon.

Because intact rocks from this ancient era are so rare, the discovery offers a unique opportunity to peer directly into Earth's formative past. These ancient minerals may preserve a record of the chemical mix left behind by that cataclysmic collision — a link between the infant Earth and its newly formed satellite.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"Our comparison was consistent with the Earth and moon having the same starting composition of around 4.5 billion years ago," Boyce said in the statement. "This supports the theory that a planet collided with early Earth and the high-energy impact resulted in the formation of the moon."

The study, conducted with collaborators from the University of Bristol, the Geological Survey of Western Australia and Curtin University, was published Oct. 31 in Nature Communications.

Samantha Mathewson joined Space.com as an intern in the summer of 2016. She received a B.A. in Journalism and Environmental Science at the University of New Haven, in Connecticut. Previously, her work has been published in Nature World News. When not writing or reading about science, Samantha enjoys traveling to new places and taking photos! You can follow her on Twitter @Sam_Ashley13.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.