This Apollo-era radio telescope in the NC mountains once spied on Soviet satellites. Now it's for sale

"What we don't want to see is this turned into a bunch of multi-million dollar homes."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Deep in the Appalachian mountains lies a hidden piece of space history. On a nearly 200-acre property tucked into the Pisgah National Forest near Rosman, North Carolina, twin 26-meter (85-foot) radio telescope antennas point skyward, listening to signals beamed to Earth from spacecraft in orbit. First built in 1962 at a cost of $5 million, the facility began its life as part of NASA's Space Tracking and Data Acquisition (STADAN) program of ground stations. At the time, the NASA Rosman Satellite Tracking Station, or simply Rosman, was one of the most advanced ground tracking facilities in the world.

Since 1998, the facility has been under private ownership and known as the Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute (PARI). For decades, PARI has hosted on-site educational programming, stargazing parties and summer camps. But a new chapter in the long, complex story of this remote ground station could soon begin. In August, the facility appeared on the commercial real estate market for $30 million. Local news outlets in Western North Carolina reported that PARI is "up for sale" as an "out of this world" opportunity.

Like all things with this storied site, however, the truth is much more complex than what meets the eye.

Tim Delisle is the director of education at PARI and where he has been involved with the facility's outreach programs for over a decade. Delisle met me on the picturesque PARI grounds on a brisk early autumn day just as the North Carolina foliage was reaching its peak fall color. As we walked the windy grounds in the shadow of the site's iconic 26-meter radio telescope, now known as "26 West," Delisle was quick to point out that PARI is not looking for the organization itself to change hands.

"We're not shutting down; we're not stopping operations," Delisle told Space.com. "PARI the organization is not for sale." Instead, Delisle said, PARI is looking to sell or lease a portion of the facility's buildings or its 192-acre grounds — ideally, to someone who wants to continue the organization's mission of STEM (science, technology, engineering and math) outreach. "We wouldn't sell the whole facility to anyone who didn't value what we're doing, and whatever that agreement would be, they would have to carve out a space for us in that sale," Delisle said.

"We're looking for somebody who, having them here, sharing the site with us, would strengthen what we do, somebody who wants to complement what we do, somebody who's really excited about our education mission, and is going to give us the funds and the flexibility to keep doing what we do."

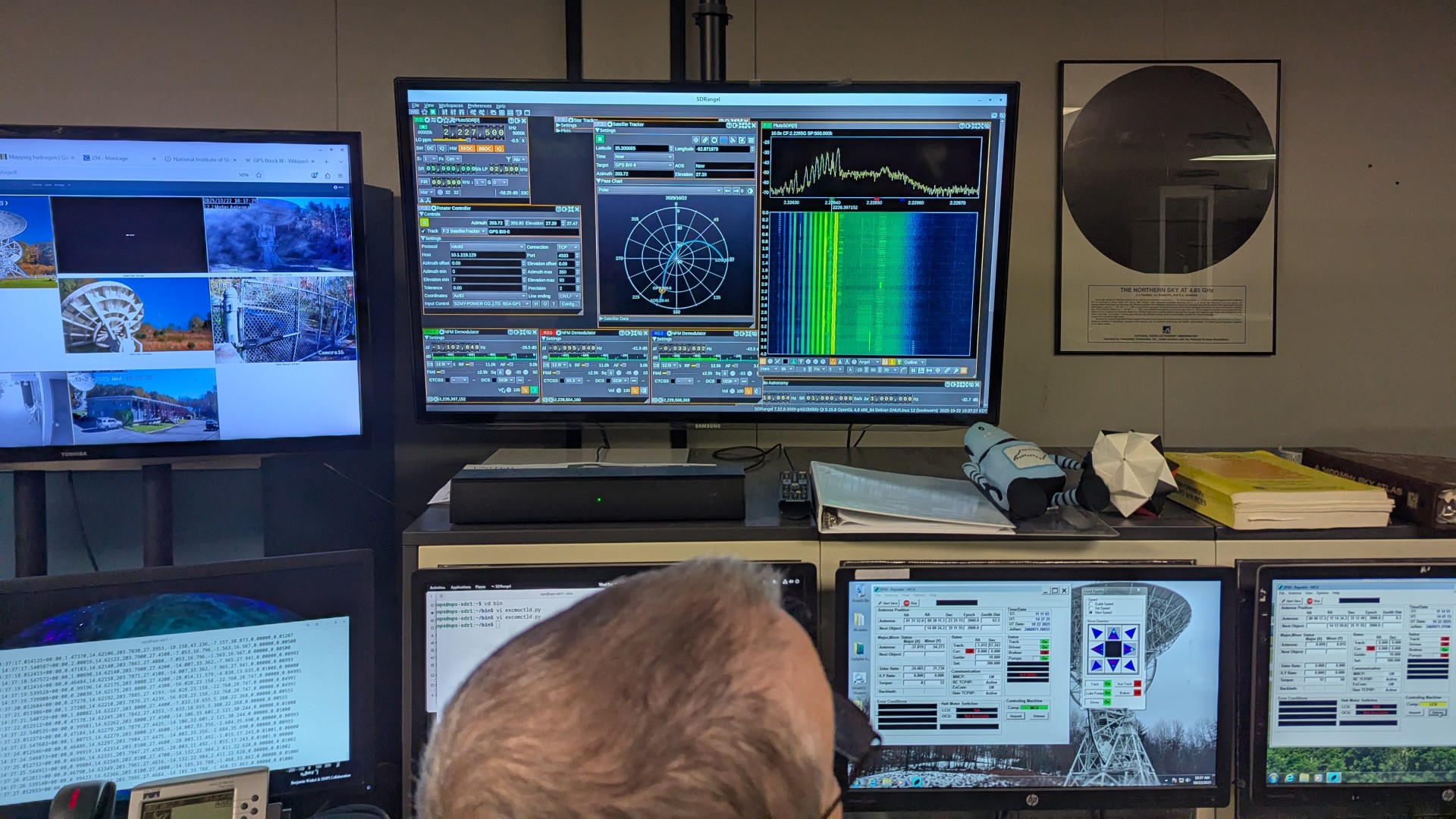

Delisle led us into a room where Lamar Owen, current chief technology officer at PARI, was tracking a U.S. GPS satellite, GPS-III SV06, which is named after Amelia Earhart. As he slewed 26 West to keep custody of the satellite, Owen explained that PARI is sometimes contracted by commercial companies to help track spacecraft in medium-Earth orbit and beyond.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"We actually did a track for [one of these companies] one week after Hurricane Helene hit last year, while we still had no power here and while the site was still heavily damaged," Owen said. "It was major."

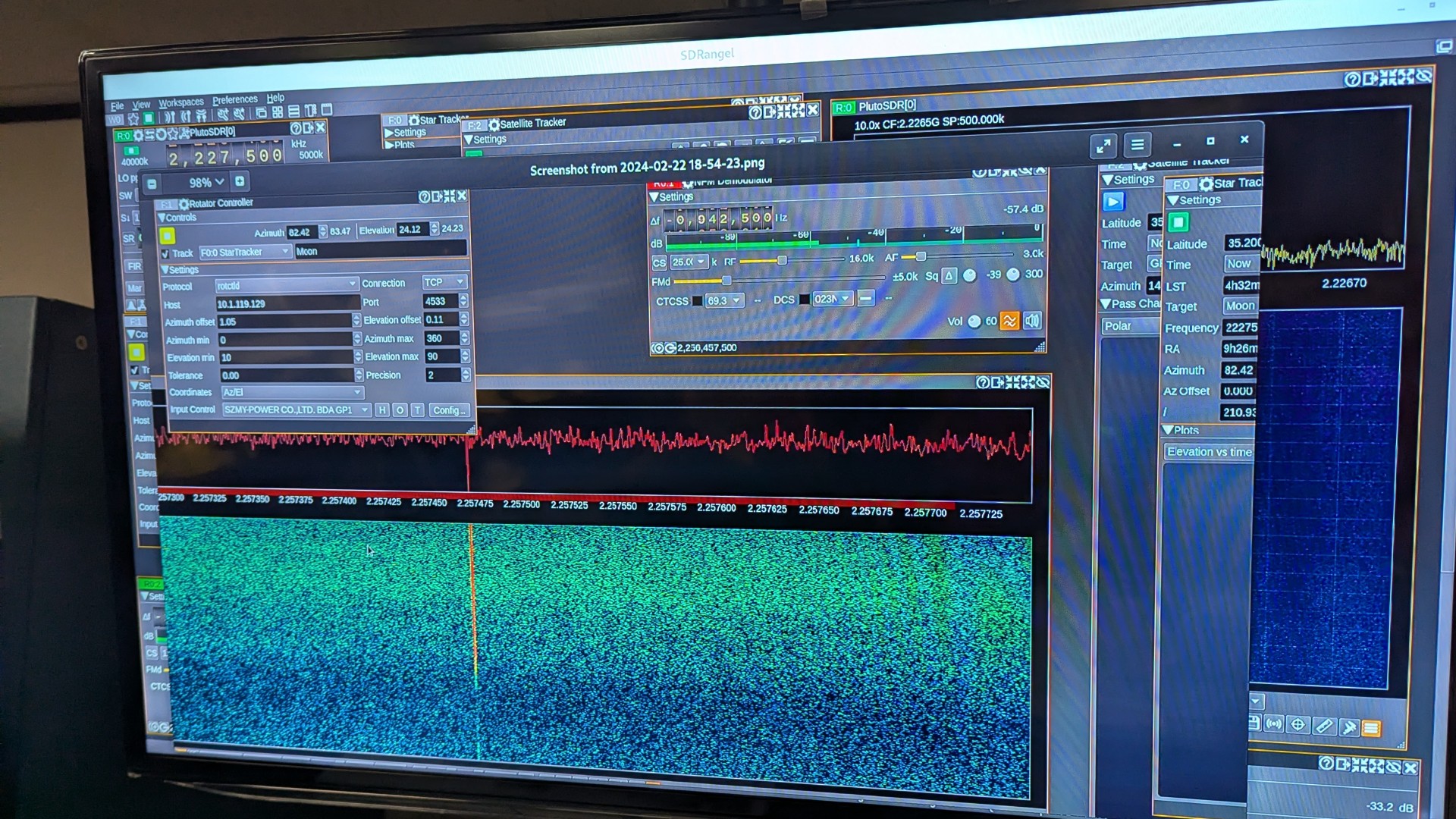

Owen then opened a screenshot from Feb. 22, 2024, when Intuitive Machines' IM-1 lunar lander, named Odysseus, touched down on the moon in a historic first for commercial spaceflight. For some 15 minutes after Odysseus reached the lunar surface, mission controllers were unable to establish a signal with the lander. But Owen says that, using 26 West, he was able to track the moon lander and determine why Intuitive Machines couldn't immediately latch onto Odysseus' signal.

"That's the Intuitive Machines lander about 10 minutes before anybody else picked it back up," Owen said, pointing to a screenshot of its signal. " I just didn't have any way of contacting them, saying 'reverse polarity!', because the signal was bouncing off the surface and that reversed its polarity," Owen said.

"So we were not an official site to do this work, but you know, we will often, when something interesting is happening, we'll often do it anyway, just to kind of build our portfolio, to say, 'Look, we did this.'"

Because PARI's antennas are ideal for lunar communications, as the IM-1 track demonstrates, the facility has responded to a NASA Request for Information to help track the agency's Orion spacecraft as it journeys to the moon and back on the upcoming Artemis 2 mission.

"And here's the thing," Owen added, "even if they don't pick us to do it officially, there's nothing to stop us from aiming a dish at Artemis and doing it anyway, because we can still receive the signal. So our plan is to make this a very public event, have schools come in and learn about what that is and what's going on."

And it wouldn't be the first time PARI's dishes have helped track NASA spacecraft.

PARI's NASA heritage

From its outset, NASA's Rosman Satellite Tracking Station was used to communicate and track some of the agency's earliest astronomical satellites, including the first successful space telescope, Orbiting Astronomical Observatory-2, which launched in 1968.

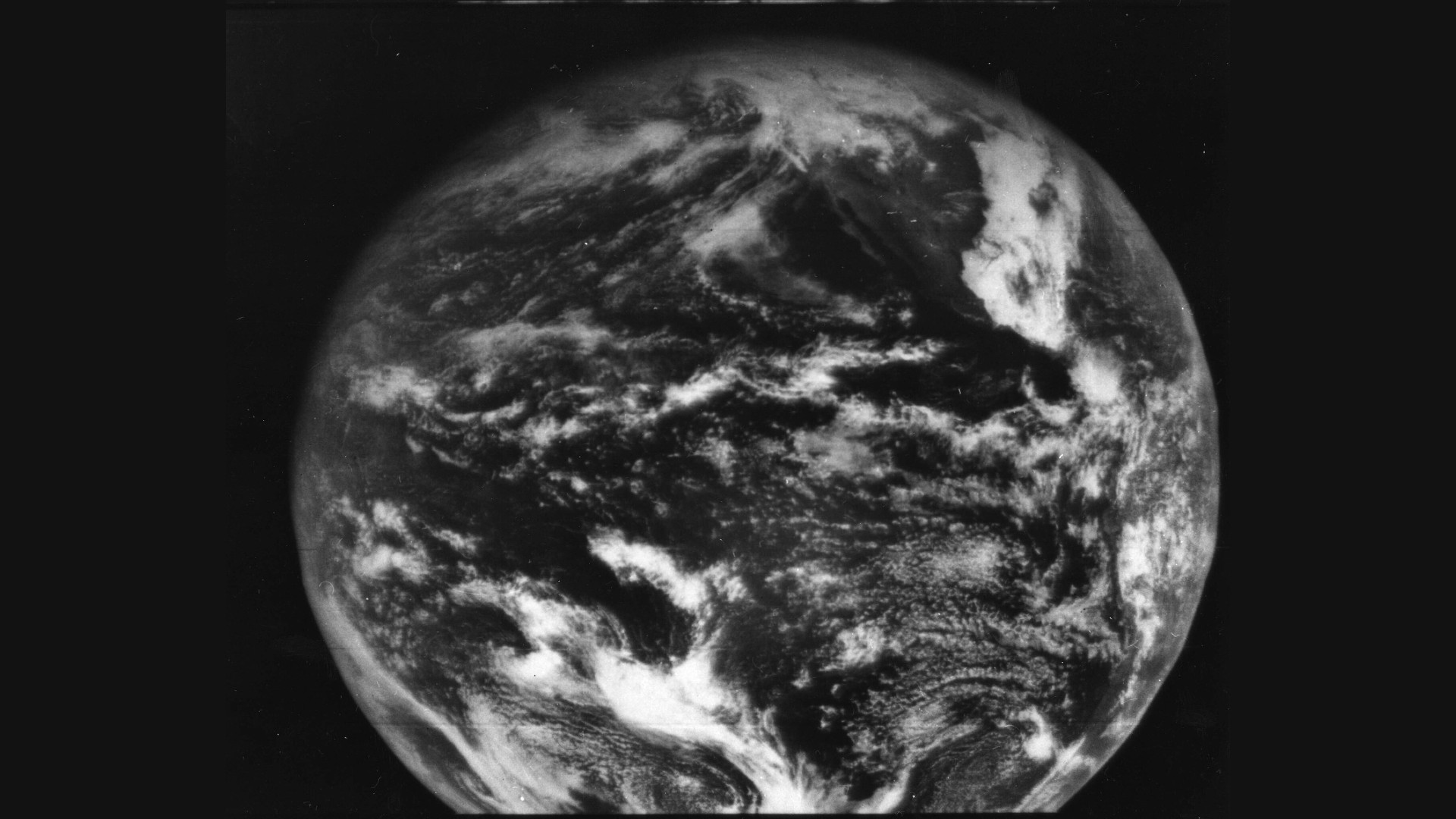

The facility also supported NASA's Applications Technology Satellite program, which paved the way for today's weather satellites, cellular and broadband spacecraft, and even the GPS system. One of those satellites, Applications Technology Satellite 1, or ATS-1, beamed home the first pictures of the entire planet Earth from geostationary orbit in 1966.

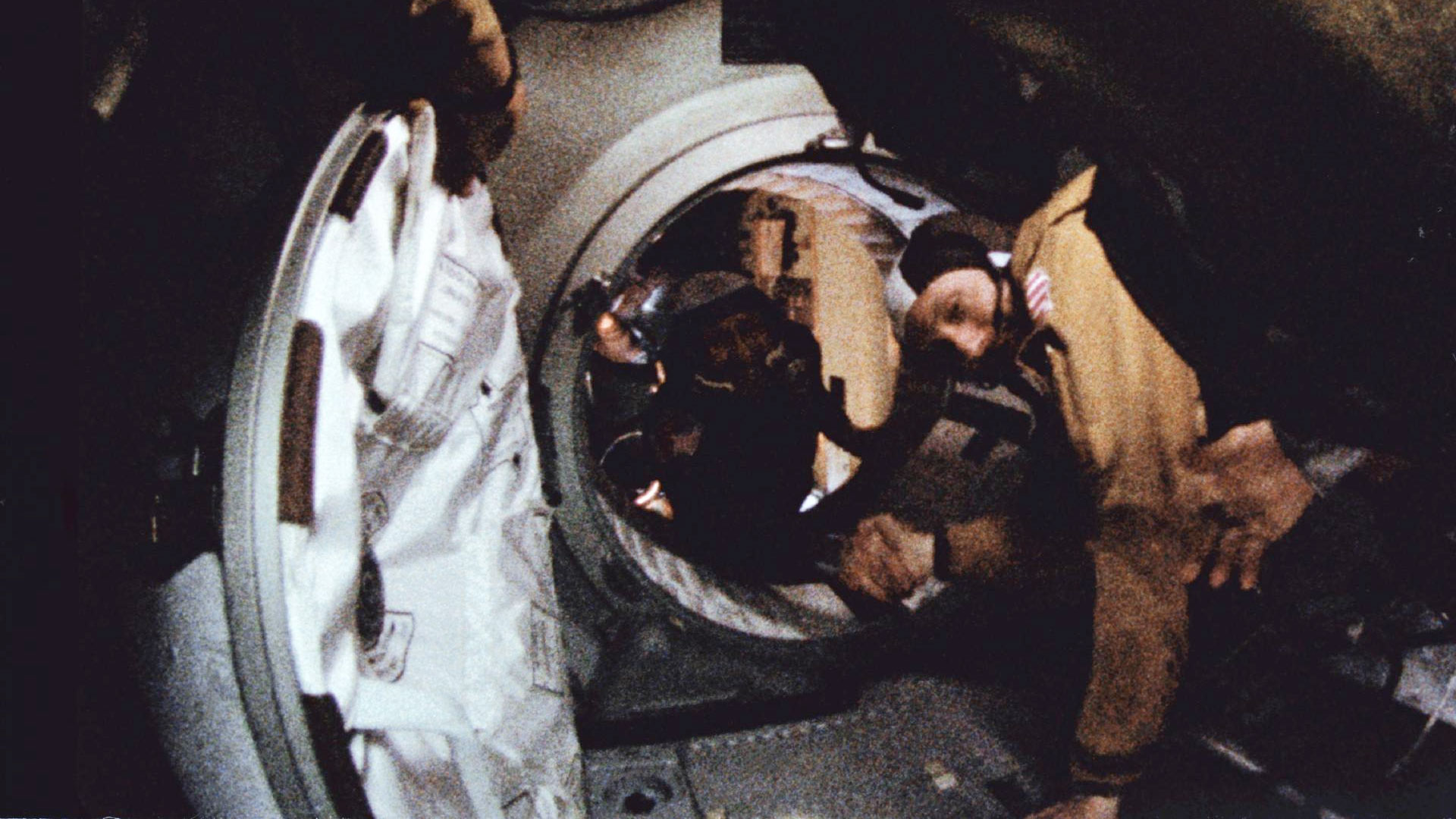

Rosman would later be used to control ATS-1 as it served as the primary communications relay between President Richard Nixon and the Apollo 11 astronauts who had just been recovered onto the aircraft carrier USS Hornet on July 24, 1969. In 1975, during the historic Apollo-Soyuz mission that saw a U.S. and Soviet spacecraft dock in orbit in the first crewed international spaceflight, a satellite under Rosman's control known as ATS-6 provided ground control communications for the mission.

But by the end of the 1970s, most of NASA's ATS satellites had been deactivated as more advanced spacecraft and instruments had been developed and launched. Other NASA satellite facilities such as Goddard Space Flight Center in Maryland were also expanding and adding new capabilities that overlapped Rosman's. Shifting budgets and new priorities at NASA were making Rosman obsolete.

"Rosman's demise as a NASA ground station was inevitable and could be traced to years of NASA's budget shortfalls, workforce consolidation and advances in technology that eliminated the need for a large global network of satellite ground stations," writes author Craig Gralley in his 2023 book "Pisgah Astronomical Research Institute: An Untold History of Spacemen & Spies."

By 1981, NASA had ceased operations at Rosman.

Spies come to Rosman

Then, in July 1981, the U.S. Department of Defense's National Security Agency (NSA) took over the facility, renaming it the Rosman Research Station. The site and what went on there immediately became classified — and remains so to this day.

"There is a cryptologic history document, and we're in book five. Entire chapters are redacted in that book," Owen said. "Except for the index, and in the index you can see Rosman Research Station is all over the place. But you can't read anything about it because every page that it's on is redacted."

We now know, largely through Gralley's research, that the NSA's Rosman Research Station would go on to be used to spy on the Soviet Union's Lourdes signals intelligence station near Havana, Cuba. Lourdes was the Soviet Union's most advanced signals intelligence facility and provided Moscow with around 70% of all intelligence data about the U.S., according to Gralley. The Lourdes site could intercept secret phone and fax transmissions and signals sent from military and commercial satellites operated by the United States. It's not hard to see why the Rosman Tracking Station was such a sensitive operation.

Owen, a lifetime Rosman resident, remembers a fairly steady military presence throughout the area during the NSA years to protect that sensitivity. "You'd hear all kinds of things going on up here, all kinds of traffic. Every once in a while, things would get a little serious, and guards would come around."

The clandestine nature of the facility also led to plenty of misinformation around the area, Owen added. "Everything was a rumor. Oh, yeah. And we kind of 'wink, wink, nod, nod' to some of those. That's why we have the stuffed aliens, the little green men in there," he said, pointing to stuffed large-eyed "grey" aliens in one of the facility's waiting areas. "People say there's aliens under the floor in an underground city or something."

While Rosman's exact missions and its role in countering or monitoring the Soviet intelligence coming out of Lourdes is unknown, the U.S. government apparently felt the facility was valuable enough to warrant a reported $200 million investment in the mid-1980s to improve the site. "Satellite dishes sprang up like mushrooms after a warm summer rain," Gralley writes.

But like mushrooms in summer, the U.S. government's investment into Rosman Research Station would eventually dry up.

PARI today

By 1995, due to changing geopolitical tides, the U.S. government decided it no longer needed the facility. The NSA disassembled most of the site's dozens of satellite dishes and several buildings' worth of signals intelligence equipment, shredding a landfill's worth of documents in the process.

The site was soon after turned over to the U.S. Forest Service and largely ignored for several years, until a group of private investors with a love of space and science saw untapped value in the site. Led by engineer Don Cline, the group formed a non-profit foundation and purchased the site from the U.S. government in January 1999 after securing congressional approval.

Since then, PARI has hosted thousands of students and adult visitors per year for hands-on educational programming, including summer camps. The facility operates dorm-style accommodations with an on-site cafeteria and luxury cabins, owns a wide range of telescopes and an inflatable planetarium. Several weddings have been held at the site.

The visitor's center even operates an impressive mineral and rock collection that is home to dozens of meteorite samples, including from well-known strikes such as the Chelyabinsk meteor, which exploded over that Russian city in February 2013.

But PARI is also home to active scientific research both on its own and by partnering with academic institutions. "We've got about a dozen instruments right now that belong to different universities. We've got some instruments that belong to a couple of government agencies, a few other research groups," Delisle said. "For instance, one is an antenna that picks up the radio collars of migratory birds. So it's not just astronomy. We have an antenna for Georgia Tech that picks up different types of lightning and electrical stuff in the atmosphere."

PARI also hosts almost half a million astronomical glass plate negatives dating back to the mid-19th century. The collection is still being used in contemporary research. "When Tabby's star was first a big thing, we were one of the groups who was able to look back at data about it at different periods in history and see that whatever it is it's doing, it's been doing it for a long time. We were able to confirm that this has been happening for, you know, a century or more," Delisle said.

PARI even partnered with the European Space Agency to help build the data set to train the Gaia observatory's onboard AI using data from the facility's glass plate archive.

But despite the site's contributions to astronomical research, Delisle stressed to Space.com that he wants to keep the original vision for PARI alive. "One of the things that [Cline] had noticed throughout his life was that fewer and fewer kids were studying STEM fields. And this was before it was called STEM," Delisle said. "And part of the reason why he founded PARI was to create those inspiring experiences; once the space race was over, one of those big sources for inspiration kind of fell off."

Delisle has been working for years to keep that inspiration alive, but funding has always been a challenge for PARI, he explained, particularly after the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily halted the site's camps and educational programs. And it's not just PARI; funding for space sciences across the United States is at a dangerous crossroads, and even some of NASA's most high-profile missions are in jeopardy of going dark.

Still, Delisle remains optimistic about PARI's future, and he sees a possible path forward through partnering with the rapidly expanding private space sector.

"If there was a space company who came in and said, 'We want to buy the dishes and the buildings to operate them, but we'll still let you use them for education and outreach,' we'd be open to that," Delisle said. "If somebody came here and wanted to build some data centers, we'd be up for that. If somebody came here who wanted to, you know, have a research and development sort of branch here for space technology, we'd be up for that, too. There's a lot of things that we'd be open to, right?"

"What we don't want to see is this turned into a bunch of multi-million dollar homes."

Before leaving PARI's visitor's center, Owen and I stood at the window next to the 26 West control room, where I used a remote control to slew the massive radio telescope. "These are still useful instruments, and they're still in use and accessible to people who want to use them," Owen said as we watched the dish turn slowly from east to west, toward the Great Smoky Mountains in the distance. "That's a piece of history. That's a working museum exhibit."

Brett is curious about emerging aerospace technologies, alternative launch concepts, military space developments and uncrewed aircraft systems. Brett's work has appeared on Scientific American, The War Zone, Popular Science, the History Channel, Science Discovery and more. Brett has degrees from Clemson University and the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. In his free time, Brett enjoys skywatching throughout the dark skies of the Appalachian mountains.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.