Walk through the asteroid strike that killed the dinosaurs with American Museum of Natural History's new 'Impact' exhibit

"It sounds like science fiction or the stuff of Hollywood movies."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

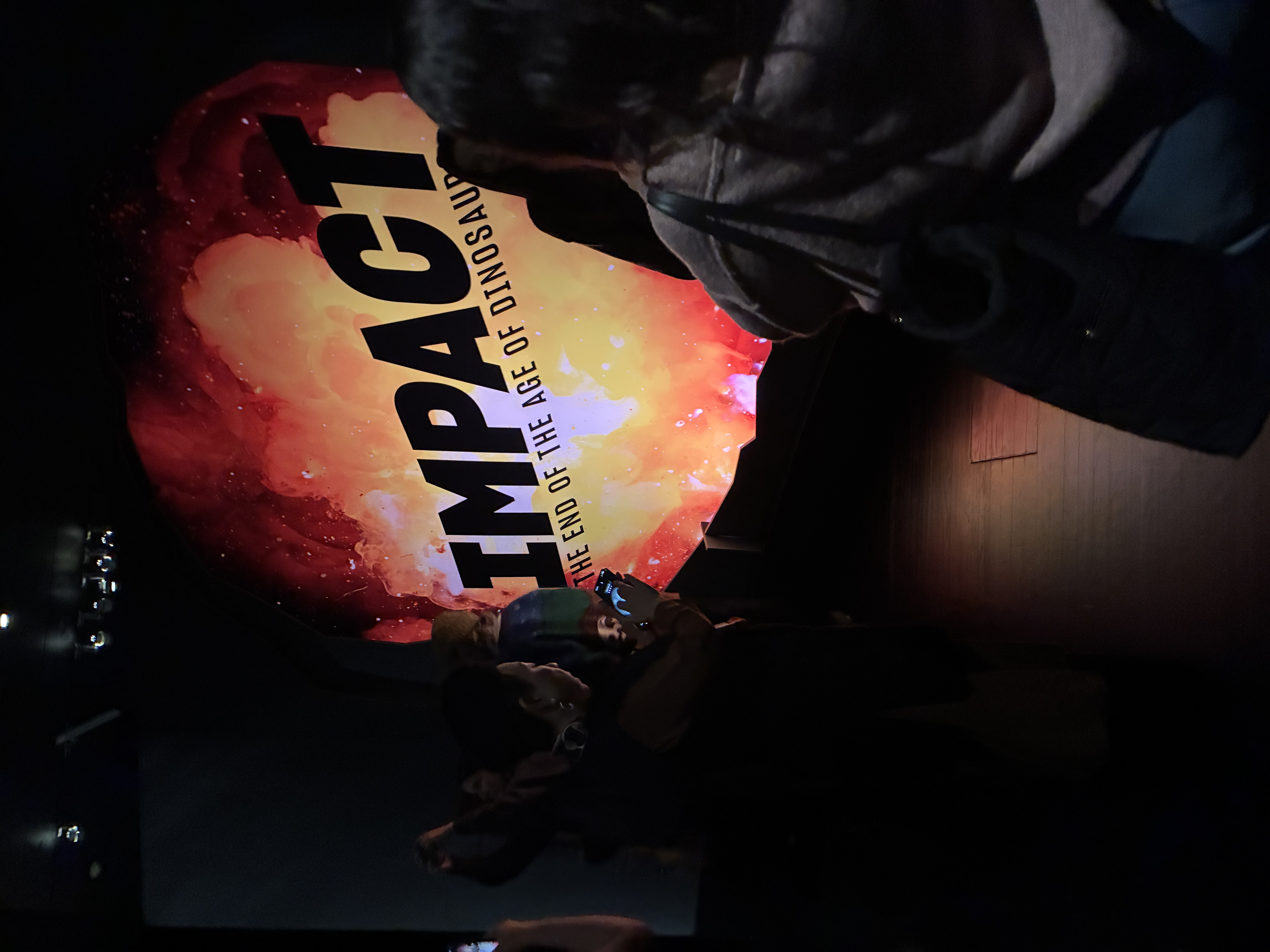

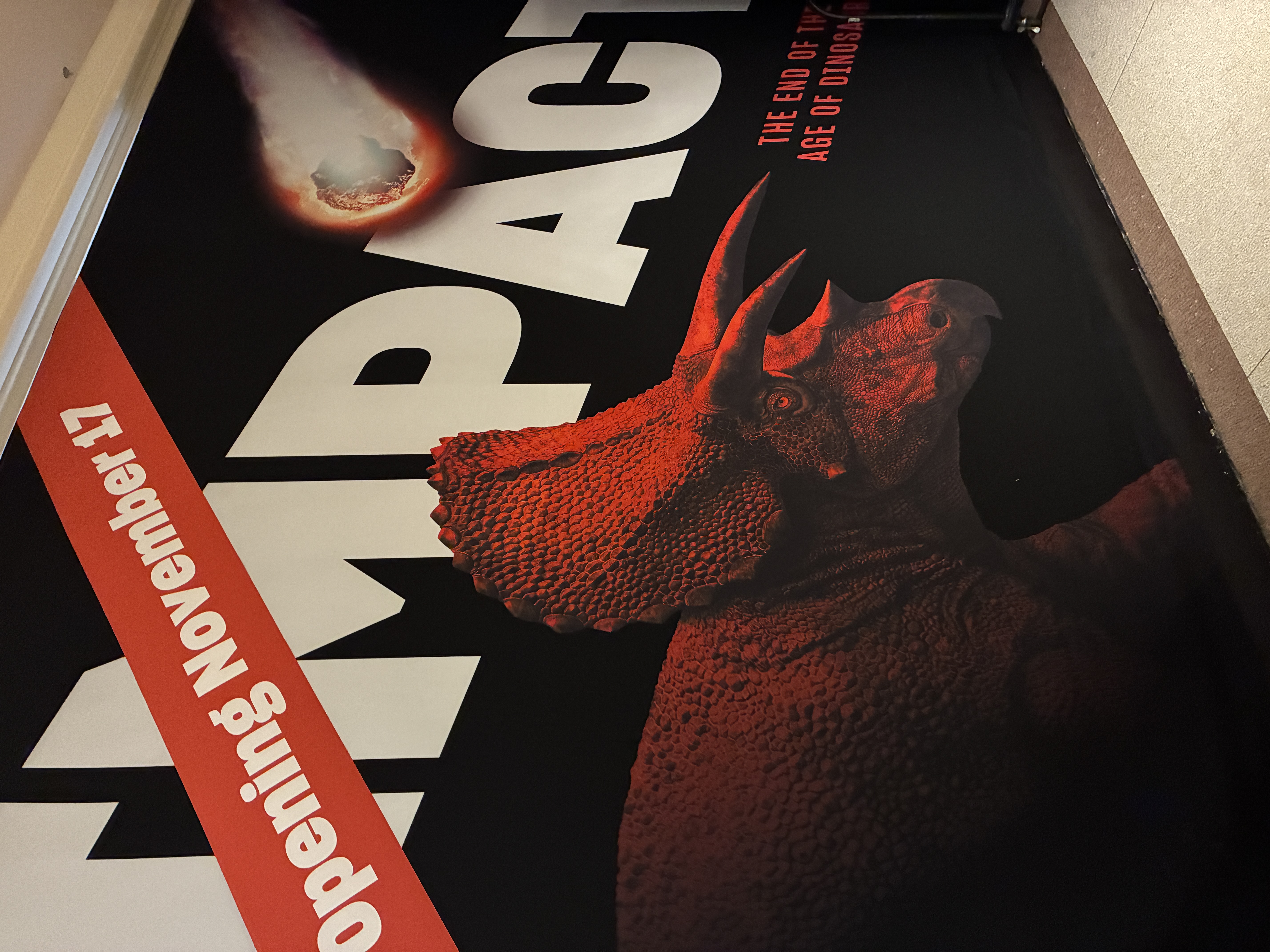

NEW YORK — The American Museum of Natural History (AMNH) in New York City has opened a new exhibition that takes a multidisciplinary perspective on the asteroid strike that ended the Cretaceous period and killed all the non-avian dinosaurs. The exhibit — aptly called "Impact" — chronicles what was, in the words of AMNH curator of paleontology Roger Benson, Earth’s "worst day of the last half-billion years."

One spring day 66 million years ago, a rock from outer space slammed into what is now the Yucatan Peninsula. The meteor was roughly the size of Mount Everest, and it struck with the force of 10 billion atomic bombs. Nearby forests instantly incinerated as atmospheric temperatures briefly soared to 500 degrees Fahrenheit. Many animals, including large dinosaurs, were buried in ash — though some were able to escape by digging underground or diving underwater.

The tremendous impact also flung a mushroom cloud of ash and dust into the atmosphere, eventually shrouding the planet in a cold gloom. Tiny glass beads rained down as far away as Wyoming. At the same time, the impact triggered landslides, earthquakes and tsunamis around the world.

A little backstory

The scene was nothing short of apocalyptic. "It sounds like science fiction or the stuff of Hollywood movies," Benson told a small crowd of reporters at a preview press event. But piecing together the story of this violent end to the age of dinosaurs has been a centuries-long, interdisciplinary process.

The first hint that something strange happened at the end of the Cretaceous period was the K-Pg boundary layer, a dark stripe of clay in the sedimentary rock record above which dinosaur fossils are absent. This layer was first recognized by geologists in the late 1700s and early 1800s. However, its exact cause — and geologic significance — remained a mystery until the 1980s. Only then did planetary scientist Walter Alvarez and his father, physicist Louis Alvarez, discover the K-Pg boundary layer contained an astonishingly high concentration of iridium, an element that is scarce on Earth's surface but abundant in space rocks. The only plausible explanation? Our planet was struck by an asteroid millions of years ago.

It was a decisive blow to another popular scientific theory at the time — the concept of gradualism, which holds that geological and evolutionary changes only unfold slowly and over long periods of time. "It represented a paradigmatic shift in people’s thinking," Neil Landman, a curator of fossil invertebrates at AMNH, told Space.com.

Since then, researchers from every corner of science have helped piece together our current understanding of the event. Meteorite experts pinpointed the impact site: the Chicxulub crater in Mexico. Invertebrate paleontologists identified widespread ocean acidification based on the mass deaths of tiny creatures called foraminifera. And evolutionary biologists and paleobotanists detailed life's recovery through the fossil record.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

"It's been a tremendous coalescence of ideas," Denton Ebel, a meteorite expert at AMNH, told Space.com.

The walkthrough

The exhibit walks guests through the event as it unfolded chronologically. First, visitors encounter panoramas depicting life at the end of the Cretaceous. In one, a massive mosasaur hunts a long-necked plesiosaur, both members of marine reptile lineages that died out after the asteroid impact. Across the way, a triceratops lumbers through a prehistoric forest alongside turtles, primitive mammals, small dinosaurs and toothed birds.

Then, visitors move into a small theater to watch a 6-minute video detailing the damage wrought by the meteor strike. Finally, the exhibit highlights the aftermath of the destruction, showing life's slow recovery and how new organisms, like mammals, moved in to fill the niches left by the dinosaurs’ extinction.

Ultimately, Benson said he hopes guests leave with a sense of life's ephemerality, as well as its resilience. We are currently living through another mass extinction, one less acute than the end of the Cretaceous, but potentially no less deadly. This time, however, humanity is the asteroid — and we have a chance to change our impact.

"We live on a changing planet," said Benson. "Rates of species extinction over the last 100 years or may be comparable to those that occurred during mass extinction events of the past. But we still have time."

The exhibit opened to the public on Nov. 17.

Joanna Thompson is a science journalist and runner based in New York. She holds a B.S. in Zoology and a B.A. in Creative Writing from North Carolina State University, as well as a Master's in Science Journalism from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program. Find more of her work in Scientific American, The Daily Beast, Atlas Obscura or Audubon Magazine.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.