Earth and Theia smashed to birth the moon, but did they first start out as close neighbors?

"The most convincing scenario is that most of the building blocks of Earth and Theia originated in the inner solar system. Earth and Theia are likely to have been neighbors."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

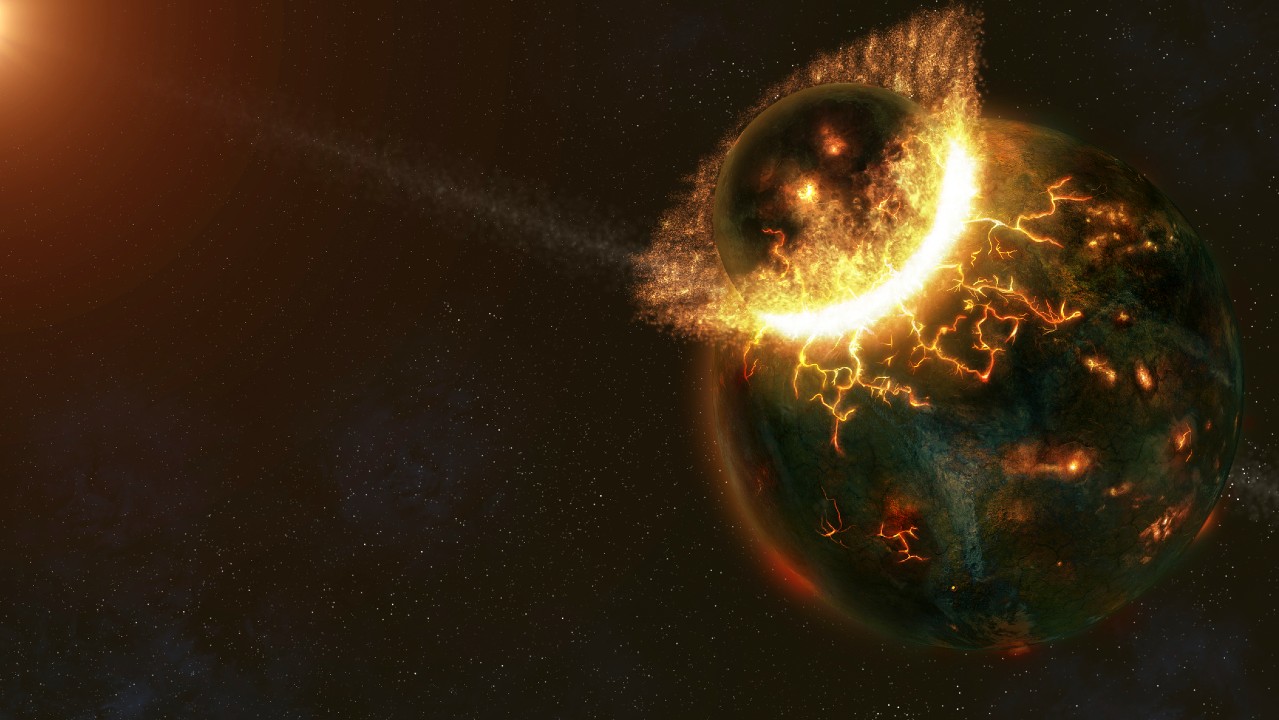

Over 4.5 billion years ago, a giant body smashed into Earth in a cosmic collision that birthed our planet's loyal companion, the moon. Now, new research indicates that this body, named Theia, may have actually formed in the inner solar system with Earth, meaning it was once our planet's neighbor.

Scientists already knew a lot about how this collision influenced Earth beyond the creation of the moon, including how it affected the shape, composition, and mass of our planet and how it shifted its orbit around the sun. However, the fact that Theia was completely obliterated in this collision means there are still many unanswered questions about the impactor itself. These include: What type of object was Theia? How big was it? What was it made of? And where in the solar system did Theia emerge from to smash into Earth?

In this new research, a team of scientists has used the information we have about Theia to create an "ingredients list" that may have composed this giant impactor, finding that this points to its place of origin in the solar system."The most convincing scenario is that most of the building blocks of Earth and Theia originated in the inner solar system," said team leader and MPS researcher Timo Hopp. "Earth and Theia are likely to have been neighbors." The team's research was published on Thursday (Nov. 20) in the journal Science.

Reconstructing Theia

Particularly useful for scientists aiming to reverse engineer Theia, like this team, are the ratios of variations of elements, called isotopes, that differ in the number of neutrons in their atomic nucleus. This is because researchers theorize that in the early solar system, isotopes were not evenly distributed, meaning the ratio of certain isotopes within a body should reveal if it formed at the edge of the solar system or closer to the sun.

This team focused on isotopes of iron, chromium, molybdenum, and zirconium found in 15 rock samples from Earth and six rocks collected from the moon by Apollo astronauts. This revealed that the Earth and the moon are, almost without question, related, something scientists already knew from isotopes of other elements. However, the team took this further and compared the isotope ratios in the Earth and moon rock samples to the composition of our planet in order to explore different combinations of Theia's size and makeup that could lead to the observed final state.

One important clue for the researchers was the fact that long before Theia slammed into Earth, our planet had formed a molten core where elements like iron and molybdenum accumulated. This led to these elements being scarce in Earth's mantle. That means any iron found in our planet's mantle, the layer between Earth's crust and its core, likely arrived after the formation of the core.

This iron may have been delivered courtesy of Theia. As team member Thosten Klein of the Max Planck Institute for Solar System Research (MPS) pointed out in a statement: "The composition of a body archives its entire history of formation, including its place of origin."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The team had a useful way to further assess the composition for Theia that they arrived at, and what it meant for its origins, using meteorites collected from the surface of Earth. These are broken-away pieces of asteroids, which formed at the same time as the planets. While the composition of Earth corresponds to a mix of known types of meteorites, originating at differing points in the solar system, the composition of what they believe to be Theia doesn't. This means hitherto unknown material could have been involved in the formation of Theia, indicating that Theia may have formed closer to the sun than Earth did.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.