Astronomers discover an enormous iron bar in the famous Ring Nebula: 'We definitely need to know more'

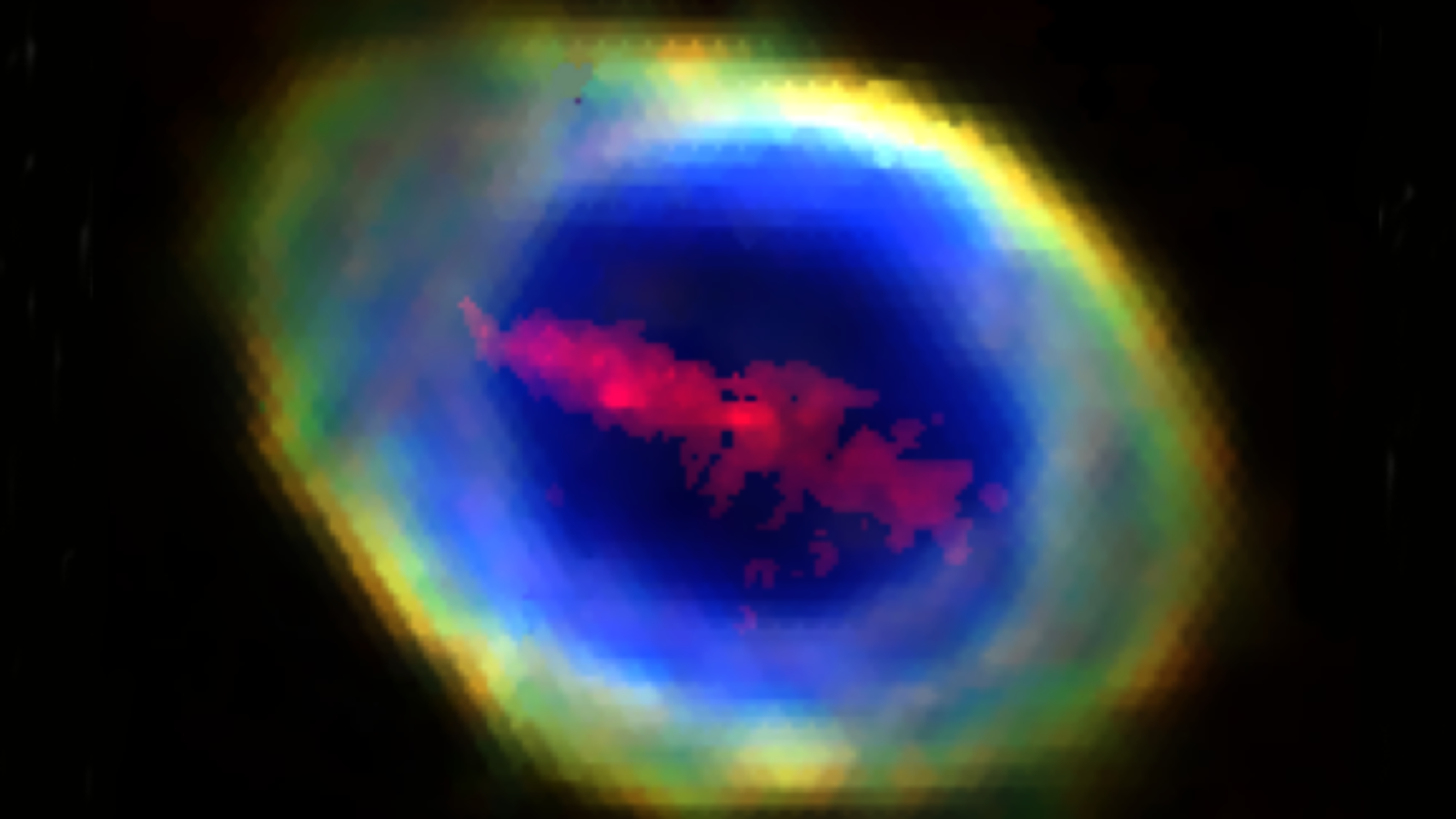

"One thing popped out as clear as anything, this previously unknown 'bar' of ionized iron atoms, in the middle of the familiar and iconic ring."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Sometimes, even the most familiar astronomical objects can hold surprises for researchers. Take the well-known Ring Nebula, which astronomers have now discovered harbors a mysterious "bar" of iron atoms.

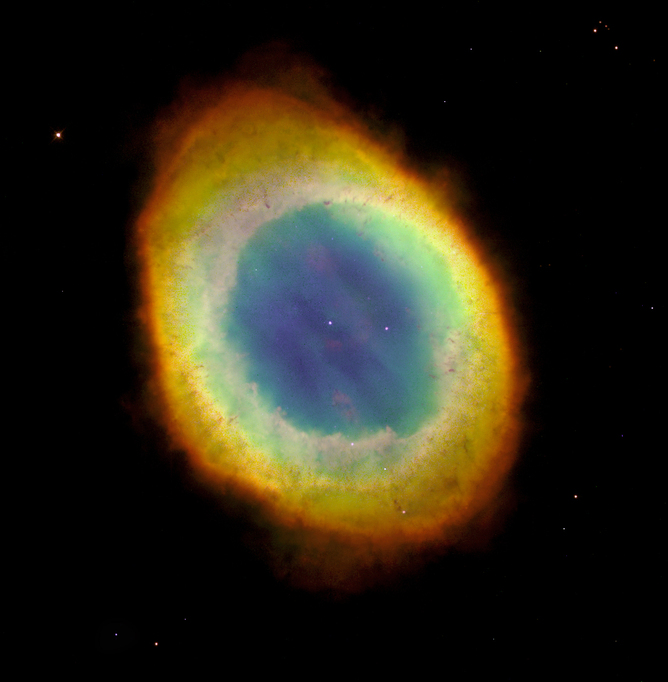

Also known as Messier 57 (M57), the Ring Nebula is a "planetary nebula" (a misleading name because there are no planets involved) located around 2,000 light-years away. It is the glowing remains of what was once a sun-like star, which ran out of fuel for nuclear fusion and shed its outer layers as its core collapsed to form a dense stellar remnant called a white dwarf.

The iron bar was discovered by a team using the William Herschell Telescope (WHT) located in the Observatorio del Roque de los Muchachos, on La Palma island, Spain, thanks to a new instrument called WEAVE (WHT Enhanced Area Velocity Explorer). The rod-like cloud of iron atoms fits within the inner layer of the oval-shaped nebula, which was first observed in 1779 in the constellation Lyra by astronomer Charles Messier. This bar extends out for around 1,000 times the distance between Pluto and the sun, and the mass of iron in the bar is around the same as the mass of Mars.

"Even though the Ring Nebula has been studied using many different telescopes and instruments, WEAVE has allowed us to observe it in a new way, providing so much more detail than before. By obtaining a spectrum continuously across the whole nebula, we can create images of the nebula at any wavelength and determine its chemical composition at any position," team leader Roger Wesson of the University College London (UCL) said in a statement.

"When we processed the data and scrolled through the images, one thing popped out as clear as anything — this previously unknown 'bar' of ionized iron atoms, in the middle of the familiar and iconic ring."

Equipped with a bundle of hundreds of optical fibers, WEAVE's Large Integral Field Unit (LIFU) mode, the team was able to capture a spectrum covering all wavelengths of visible light across the entire face of the Ring Nebula, something that has not been possible before. It would not have been possible to discover the iron bar without this new approach to imaging the Ring Nebula.

Just how this iron bar formed remains a mystery to Wesson and colleagues. One possibility is that it is related to how the star ejected its outer layers and how this process progressed. Alternatively, the formation of this arc of iron plasma could be the result of the Ring Nebula's doomed star vaporizing an orbiting rocky planet as its outer layers puffed out.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

If that is the case, the Ring Nebula could be a portent of what awaits Earth in around 5 billion years when the sun runs out of fuel for nuclear fusion and puffs out to become a red giant."We definitely need to know more — particularly whether any other chemical elements co-exist with the newly-detected iron, as this would probably tell us the right class of model to pursue," team member and UCL astronomer Janet Drew said. "Right now, we are missing this important information."

To discover the mechanism behind the creation of this iron bar, the team is planning a follow-up study with WEAVE and its LIFU mode at greater resolution.

"The discovery of this fascinating, previously unknown structure in a night-sky jewel, beloved by skywatchers across the Northern Hemisphere, demonstrates the amazing capabilities of WEAVE," Scott Trager, WEAVE Project Scientist based at the University of Groningen, said. "We look forward to many more discoveries from this new instrument."

That could include discovering if any other planetary nebulas like the Ring Nebula also contain unexpected structures.

"It would be very surprising if the iron bar in the Ring Nebula is unique," Wesson concluded. "So hopefully, as we observe and analyse more nebulae created in the same way, we will discover more examples of this phenomenon, which will help us to understand where the iron comes from."

The team's research was published on Thursday (Jan. 15) in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.