It's the Great Pumpkin (Shaped Star), Charlie Brown!

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

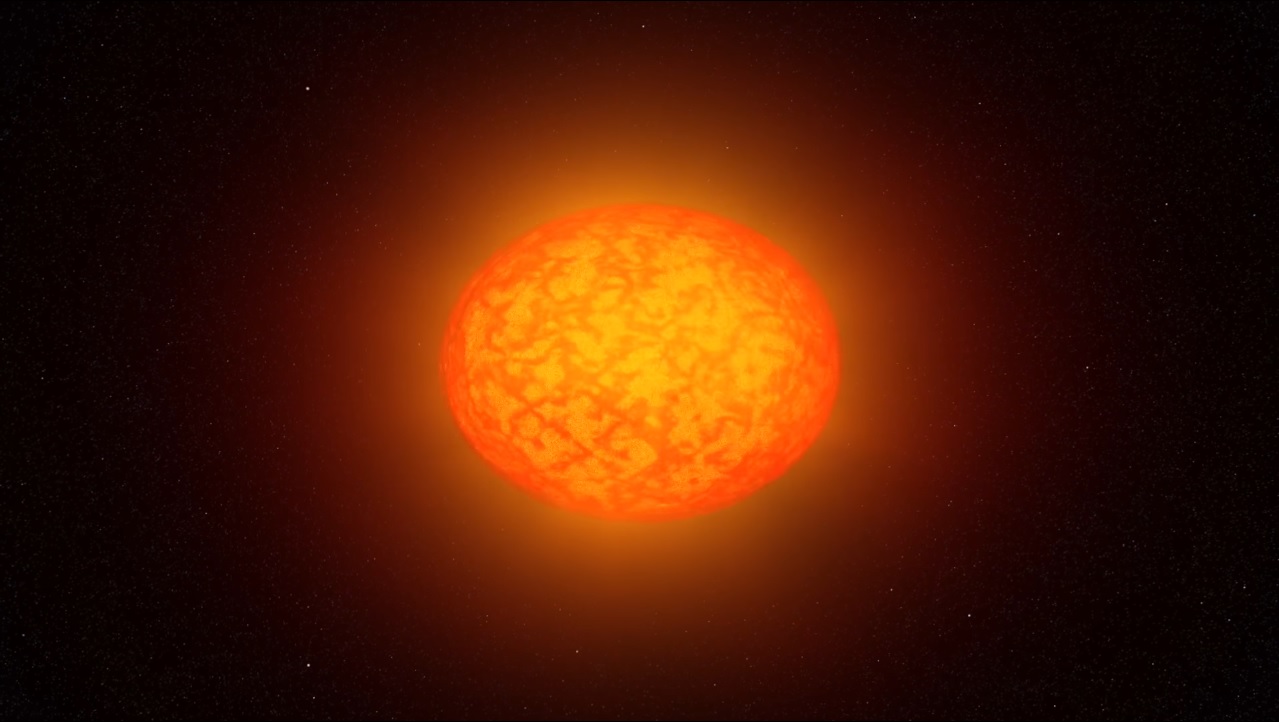

A new NASA video explains the origin of a mammoth, pumpkin-shaped star, which is blasting off powerful X-rays and spinning so fast it's squashed to look like the festive gourd.

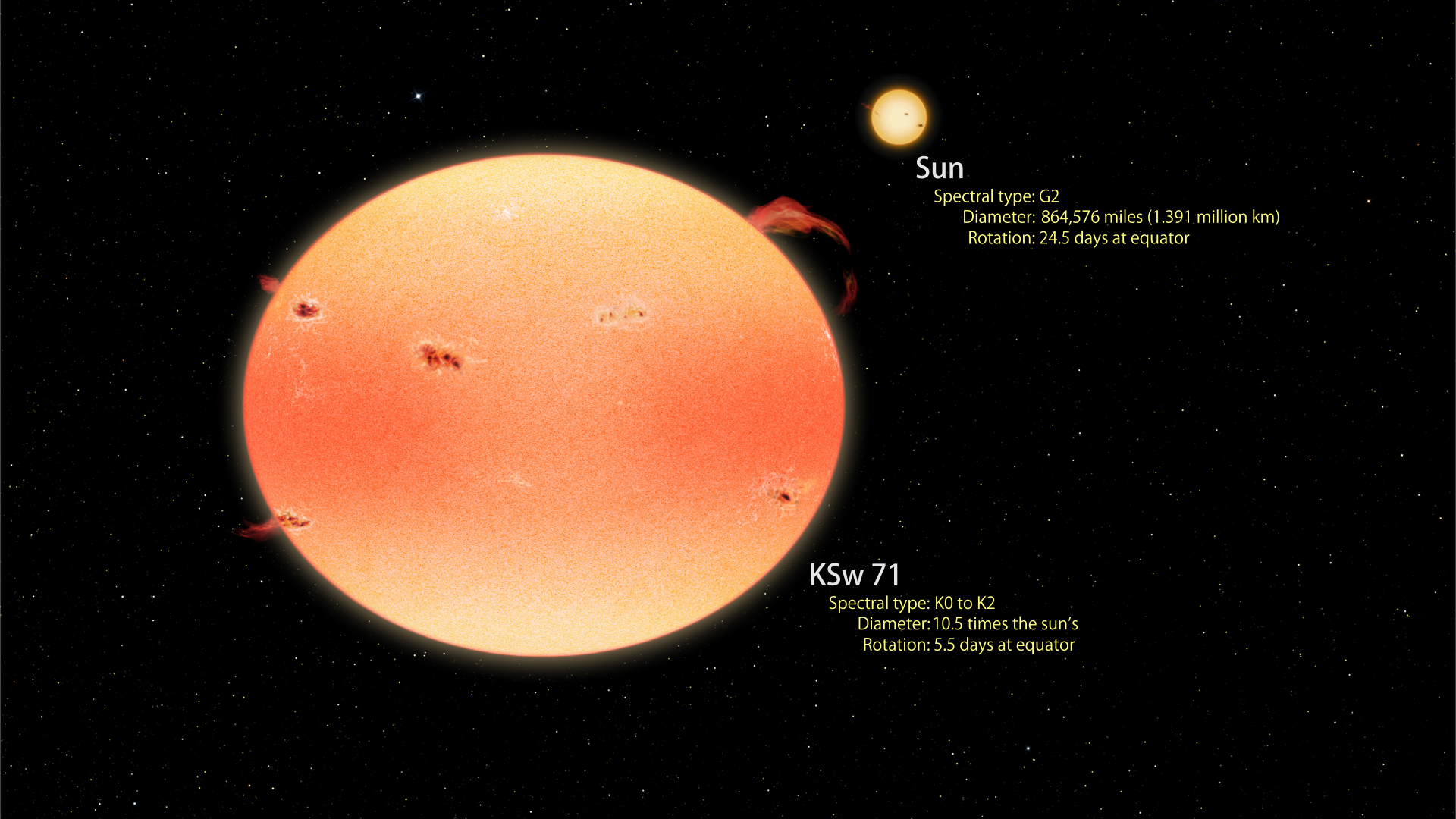

The massive orange star, called KSw 71, is the most extreme found in a new study. It is more than 10 times the size of Earth's sun and puts out 4,000 times the peak level of X-rays the sun releases. Despite the object's girth, it rotates four times faster than the sun does.

Researchers combined data from NASA's Kepler space telescope and Swift X-Ray Telescope to search for light sources letting off intense X-rays. In addition to discovering many other features, the group found 18 hyperactive stars whose furious spins lead to an average release of 100 times the sun's X-ray radiation. [These Scary Things in Space Will Haunt Your Dreams]

"These 18 stars rotate in just a few days on average, while the sun takes nearly a month," Steve Howell, an astrophysicist at NASA's Ames Research Center in California and lead author on the new work, said in a statement. "The rapid rotation amplifies the same kind of activity we see on the sun, such as sunspots and solar flares, and essentially sends it into overdrive."

The team determined the stars' squashed shapes by measuring variations in the objects' brightness: The poles glow brighter and the equator is darker in each of these stars as rotation flattens them. (The scientists also observed the wavelengths of light released by the objects using the Palomar Observatory in California.)

A 40-year-old model offers clues to the nature of the violent dance behind such large, active stars, NASA officials said in the statement. Ronald Webbink, a researcher at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, wrote in 1976 about what would happen when one star in a binary system ran out of fuel and began to expand. That star and its partner would whirl around each other faster and faster and eventually merge, leaving behind a whole lot of gas (which would disperse over time) and one big rapidly spinning star, the researchers said. [Haunting Photos: The Spookiest Nebulas in Space]

The number of such stars spotted seems to match the predicted population well, the team said — and expanding their survey to the whole field charted by Kepler should reveal around 160 of the plump pumpkins.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The new work was detailed online Oct. 25 in The Astrophysical Journal (the print release is Nov. 1).

Email Sarah Lewin at slewin@space.com or follow her @SarahExplains. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Sarah Lewin started writing for Space.com in June of 2015 as a Staff Writer and became Associate Editor in 2019 . Her work has been featured by Scientific American, IEEE Spectrum, Quanta Magazine, Wired, The Scientist, Science Friday and WGBH's Inside NOVA. Sarah has an MA from NYU's Science, Health and Environmental Reporting Program and an AB in mathematics from Brown University. When not writing, reading or thinking about space, Sarah enjoys musical theatre and mathematical papercraft. She is currently Assistant News Editor at Scientific American. You can follow her on Twitter @SarahExplains.