Scientists get 1st good look at a 'vampire star' feeding on its victim

"If you were able to stand somewhat close to the white dwarf's pole, you would see a column of gas stretching 2,000 miles into the sky, and then fanning outward."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

Using NASA's Imaging X-ray Polarimetry Explorer (IXPE) spacecraft, astronomers have obtained their first view of the inner region around a dead white dwarf star that is vampirically feeding on a stellar companion.

The team from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) was able to perform a detailed study of the previously inaccessible highly energetic region immediately surrounding a white dwarf in the system EX Hydrae, located around 200 light-years from Earth.

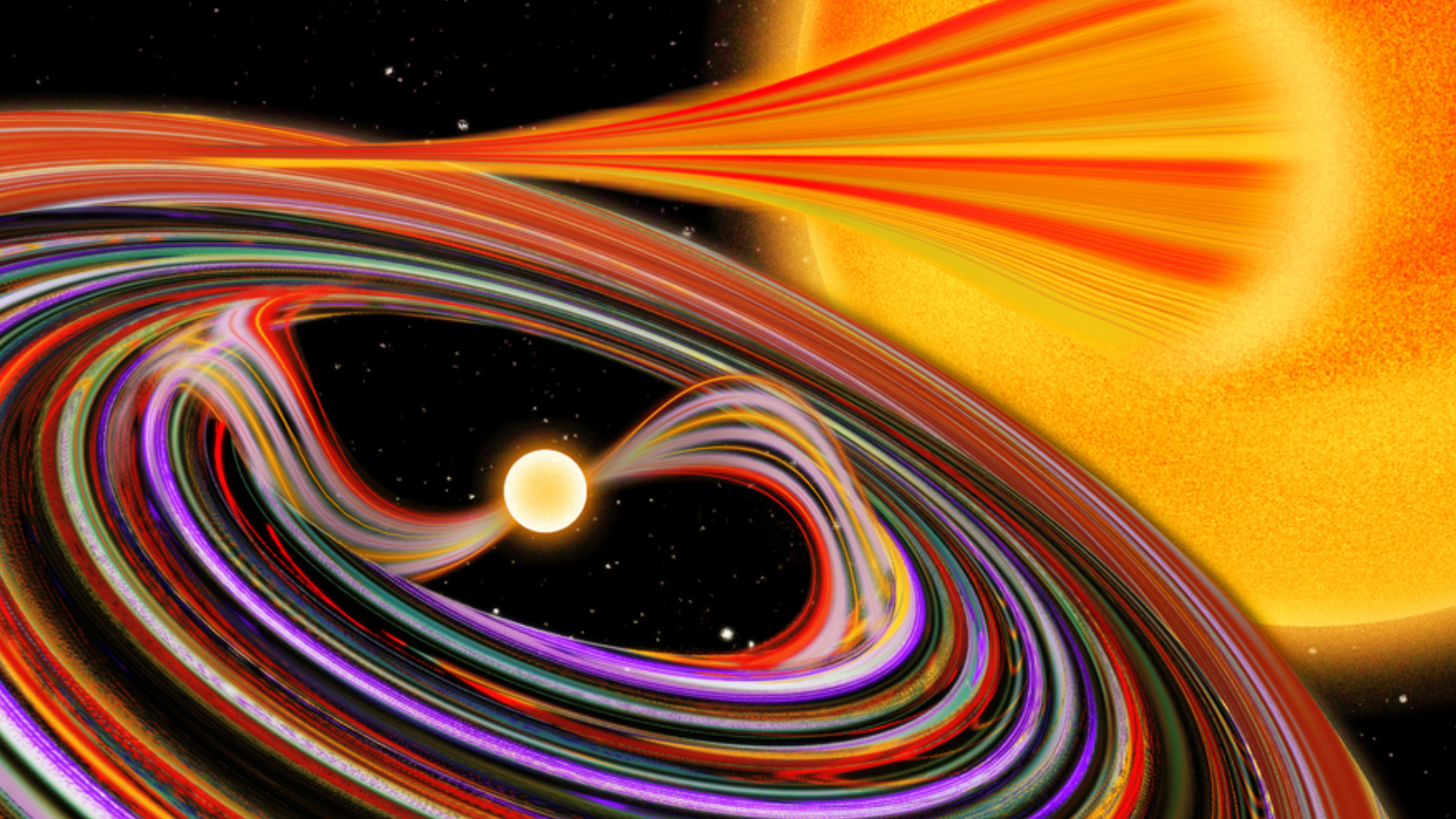

The system is part of a class called an "intermediate polar," known for emitting a complex pattern of radiation, including X-rays. EX Hydrae comprises a white dwarf, the end stage of life for stars of similar masses to the sun, and its victim star, which completes an orbit of the dead star every 98 minutes. That makes EX Hydrae one of the closest intermediate polar binaries ever discovered.

Not only did the researchers discover a high degree of polarization among the X-rays, which describes agreement in the direction the waves that comprise electromagnetic radiation are angled in, but they were also able to trace this energetic radiation to a 2,000-mile-tall (3,200 kilometers) column of blisteringly hot stellar material being pulled from the companion star, dropping onto the white dwarf.

That's around half the radius of the white dwarf itself and much larger than scientists had previously estimated for such a structure. The team also detected X-rays reflecting off the surface of the white dwarf before being scattered, something that has been predicted but was never previously confirmed.

Intermediate polars earned their name due to variations in the strength of white dwarfs' magnetic fields. When the magnetic field is particularly strong, these dead stars pull material from their companion stars, which then flows toward the white dwarfs' poles. However, when the magnetic fields of white dwarfs are weak, stripped material forms swirling structures called accretion disks around white dwarfs. From there, this stolen stellar matter is then gradually fed to the surfaces of the stellar remnants.

The situation is more complex for vampire white dwarfs with intermediate-strength magnetic fields. Scientists have predicted that, for these systems, an accretion disk should still be formed, but it should be dragged toward the poles of these white dwarfs. The magnetic fields in these systems should then hoist up this material, creating a fountain of stellar matter, or an "accretion curtain," that rains down on white dwarfs' magnetic poles at millions of miles per hour.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Scientists have predicted that this downward-flowing material should slam into still-falling matter previously lifted by magnetic fields, creating columns of turbulent gas that can reach temperatures of millions of degrees Fahrenheit, emitting X-rays in the process.

In January 2025, the research team aimed to test this idea by studying the EX Hydrae system with around seven Earth-days' worth of observations conducted with IXPE.

The findings demonstrate the effectiveness of a technique called "X-ray polarimetry," which measures the polarization of X-rays, in studying extreme and violent stellar environments.

"We showed that X-ray polarimetry can be used to make detailed measurements of the white dwarf's accretion geometry," team leader Sean Gunderson, from MIT's Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research, said in a statement. "It opens the window into the possibility of making similar measurements of other types of accreting white dwarfs that also have never had predicted X-ray polarization signals."

Polarized findings

Waves of light oscillate at a right angle to the direction in which that light is propagating, but the angle at which they oscillate can be influenced by magnetic and electric fields. Additionally, when light bounces off a surface, it can become polarized, meaning the oscillation of light waves is organized into a common direction. By studying polarized light, researchers can learn more about the object it has scattered off.

Launched in 2021, IXPE is NASA's first mission designed to detect polarized X-rays, with the spacecraft having studied some of the universe's most extreme objects and events, such as neutron stars, black holes, and supernovae. This is the first time that IXPE has been directed to study an intermediate polar system, a smaller object but still a strong emitter of X-rays.

"We started talking about how much polarization would be useful to get an idea of what's happening in these types of systems, which most telescopes see as just a dot in their field of view," said team member Herman Marshall of MIT. "With every X-ray that comes in from the source, you can measure the polarization direction. You collect a lot of these, and they're all at different angles and directions, which you can average to get a preferred degree and direction of the polarization."

Marshall, Gunderson and colleagues found an 8% polarization degree in X-rays from EX Hydrae, which is much higher than theoretical models predicted. Following this discovery, the scientists confirmed that the X-rays did indeed originate from a column of colliding gas that is around 2,000 miles tall.

"If you were able to stand somewhat close to the white dwarf's pole, you would see a column of gas stretching 2,000 miles into the sky, and then fanning outward," Gunderson said.

By measuring the direction of the polarization of these X-rays, the team was able to confirm that this high-energy radiation is bouncing off the surface of the white dwarf before traveling through space.

"The thing that's helpful about X-ray polarization is that it's giving you a picture of the innermost, most energetic portion of this entire system," team member and MIT scientist Swati Ravi added. "When we look through other telescopes, we don't see any of this detail."

The team now intends to expand its investigation of the environments around vampire stars beyond EX Hydrae to other feeding white dwarf systems. This could ultimately help better understand the final state of these systems — the Type Ia supernova explosions that emerge from the overfeeding of the dead stars and usually result in the total destruction of the white dwarf.

"There comes a point where so much material is falling onto the white dwarf from a companion star that the white dwarf can't hold it anymore, the whole thing collapses and produces a type of supernova that's observable throughout the universe, which can be used to figure out the size of the universe," Marshall concluded. "So, understanding these white dwarf systems helps scientists understand the sources of those supernovae, and tells you about the ecology of the galaxy."

The team's research was published on Nov. 10 in The Astrophysical Journal.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.