Kepler Planet-Hunting Spacecraft Bounces Back After Glitch

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

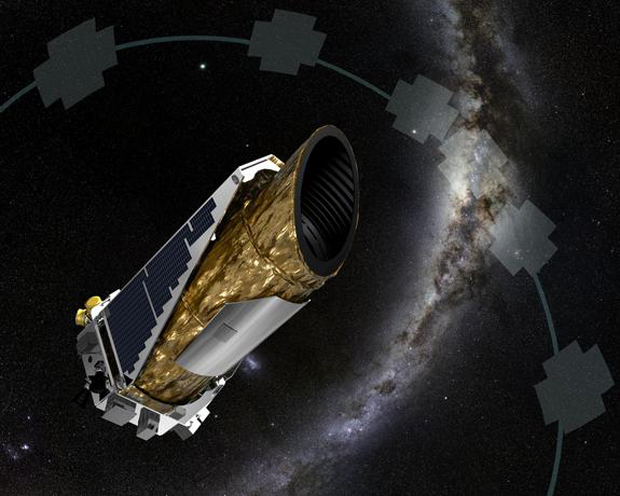

NASA's Kepler spacecraft, the most prolific exoplanet hunter of all time, has bounced back from a mysterious glitch and may be able to resume operations soon.

Mission managers succeeded in getting Kepler out of "emergency mode" (EM) Sunday (April 10), and the space telescope is in a stable state with its antenna pointed toward Earth, allowing communications to resume.

"Once data is on the ground, the team will thoroughly assess all onboard systems to ensure the spacecraft is healthy enough to return to science mode and begin the K2 mission's microlensing observing campaign, called Campaign 9," Kepler mission manager Charlie Sobeck, of NASA's Ames Research Center in Moffett Field, California, said in a statement. "This checkout is anticipated to continue through the week." [Gallery: A World of Kepler Planets]

Kepler's handlers discovered on Thursday (April 7) that the spacecraft had gone into EM — the lowest operational mode — for the first time ever. They still don't know what caused the anomaly, though they have ruled out some possibilities.

For example, Kepler went into EM about 14 hours before a planned maneuver that would have pointed the spacecraft toward the center of the Milky Way galaxy for the above-mentioned Campaign 9. So the team doesn't think the maneuver, or the observatory's orientation-maintaining reaction wheels, were responsible.

"An investigation into what caused the event will be pursued in parallel, with a priority on returning the spacecraft to science operations," Sobeck wrote.

The $600 million Kepler mission launched in March 2009, tasked with determining how commonly Earth-like planets occur around the Milky Way. The observatory has been incredibly successful, spotting more than 1,000 confirmed exoplanets to date — more than half of all known alien worlds — as well as 3,500 additional "candidates," the vast majority of which will likely turn out to be the real deal.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

In May 2013, the second of Kepler's four reaction wheels failed, ending the spacecraft's original planet hunt. But mission team members figured out how to stabilize Kepler with the aid of sunlight pressure, and the spacecraft began the new K2 mission in 2014.

Kepler is still hunting for exoplanets — which it does by noting the tiny brightness dips caused when alien worlds pass in front of their stars from the spacecraft's perspective — during K2, but on a more limited scale. The observatory is also studying a wide range of cosmic objects and phenomena, including supernovae and bodies in our own solar system such as asteroids and comets, during a series of K2 "campaigns."

Follow Mike Wall on Twitter @michaeldwall and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook or Google+. Originally published on Space.com.

Michael Wall is a Senior Space Writer with Space.com and joined the team in 2010. He primarily covers exoplanets, spaceflight and military space, but has been known to dabble in the space art beat. His book about the search for alien life, "Out There," was published on Nov. 13, 2018. Before becoming a science writer, Michael worked as a herpetologist and wildlife biologist. He has a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology from the University of Sydney, Australia, a bachelor's degree from the University of Arizona, and a graduate certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz. To find out what his latest project is, you can follow Michael on Twitter.