The Immortals Behind the Stars (Op-Ed)

Jordanna Max Brodsky is the author of the new book "The Immortals," a modern tale that follows the ancient Artemis. Brodsky hails from Virginia and holds a degree in History and Literature from Harvard University. Living in Manhattan with her husband, she often sees goddesses in Central Park and wishes she were one. Brodsky contributed this article to Space.com's Expert Voices: Op-Ed & Insights.

The ancient Greeks called constellations katasterismoi, meaning "placings of the stars" — placed by the gods. The Greeks believed the Olympians put those people, animals and objects in the heavens for a reason: to serve as unmistakable lessons on proper behavior. Often, entire stories play out across the sky, traced from one constellation to the next.

Much of the zodiac (a word coined from the Greek zodiakos kuklos, or "circle of little animals") represents beasts defeated by the great hero Heracles as part of his labors, such as Leo the Nemean Lion, Cancer the Crab, and Taurus the Cretan Bull. Other tales are even more bloody and brutish, reminding humanity of the punishments that await mortals who refuse to pay homage to the gods.

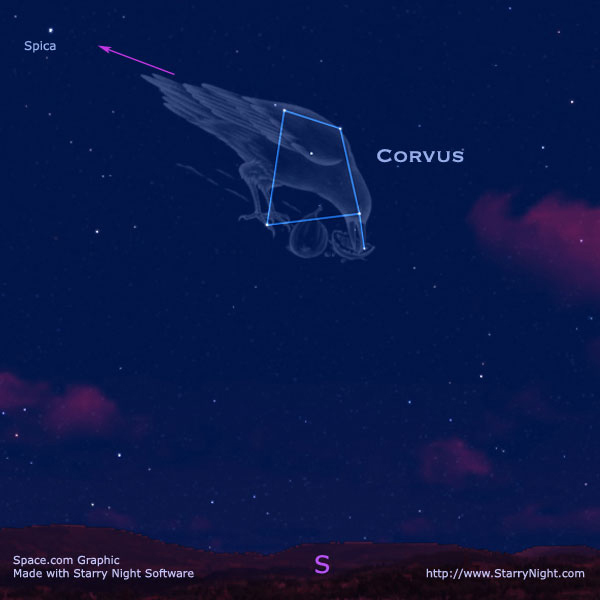

Artemis, the virgin Greek goddess of the hunt, is credited with "placing" more than her fair share of constellations — Ursa Major, Orion and Corvus, to name a few. So many, in fact, that one of her more poetic monikers is Lady of the Starry Host. [Hail Hydra! A Monstrous Constellation Explained ]

My book "The Immortals" (Orbit Books, 2016) is a contemporary fantasy about Artemis, who now prowls the shadows of modern Manhattan under the name Selene DiSilva, defending women from the men who abuse them. Like so many New Yorkers, Selene rarely sees the heavens above — too much light pollution, too many skyscrapers. But when she does, she reads her own history in the patterns of the stars.

Today, we know that humans arbitrarily codified the constellations — there is no scientific reason to group the stars. Yet civilizations throughout history have identified constellations, and even now we still call them by their old Greek or Roman names for a reason: The myths make the stars seem a little less distant , the universe a little less vast. Call that anthropocentric hubris if you like, but it's a universal impulse nonetheless.

So why fight it? Much of our astronomical knowledge, from the identification of the zodiac to the prediction of eclipses, dates back to the ancient world. Sure, they believed in a geocentric universe, but they got a lot of other stuff right. And if nothing else, the myths are as captivating, dramatic and action-packed as any modern blockbuster.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

As a primarily oral civilization, the ancient Greeks told many versions of the constellation myths, so there's never one "correct" story. What we do know comes from rare and often fragmentary written sources. But, as a writer, that's part of why I love mythology: There's always room for our own imagination to fill in the blanks.

Here are a few of my favorite stories behind the stars.

Orion: Artemis's lost love

Orion is the sole male hunting companion of the chaste Artemis . He wants to marry her, but her jealous twin brother Apollo can't let that happen. One day, when Orion is swimming far out at sea, Apollo points to the speck on the horizon and dares his sister to strike the target with her arrows. She accepts the challenge and, being the Goddess of Archery, easily hits the mark. When she realizes her brother has betrayed her, and that she has murdered her friend, she places Orion's body in the stars. Another version of the tale, less personally engaging but more ecologically relevant, claims that Orion boasted that he could kill all the beasts of the Earth and that, as punishment for his hubris, Artemis sent a scorpion to kill him, later turning them both into constellations so they could continue their chase for eternity. Even now, as Orion sets, Scorpius rises.

Ursa Major: The cursed she-bear

The beautiful princess Callisto swears herself to Artemis as a chaste hunting companion. Zeus, the King of the Gods (and a notorious womanizer), seduces the princess anyway. When Artemis notices Callisto's swollen belly, she turns the girl into a she-bear as punishment for breaking her vow of chastity. Years later, Callisto's son, Arcas, sees a bear wandering through the temple grounds. Unaware that the bear is his mother, he sends an arrow through its heart. Callisto ascends to the heavens as Ursa Major, the Great Bear, and Arcas as either Ursa Minor or Boötes, which the Greeks originally called Arctophylax, or Bear-Watcher.

Cassiopeia: The boastful queen

Anyone who saw "Clash of the Titans" might remember that Cassiopeia's daughter, Andromeda, was a princess chained to a rock as an offering to a great sea monster. The hero Perseus defeats the monster, saves the princess, and wins himself a bride. But why was she chained up in the first place? Because Cassiopeia bragged that her daughter was more beautiful than the sea nymphs. Poseidon, the Sea God, sends fearsome Cetus the Whale to attack the city as punishment for the queen's hubris. To commemorate the story, the gods placed the entire family, including Andromeda's father, Cepheus, in the stars. For her boasting, Cassiopeia must traverse the heavens lying on her back. [Cassiopeia: The Banished Queen Ruling the Night Sky]

Corvus: The Tattling Crow

Apollo's pregnant lover Coronis, a princess of Thessaly, betrays him by sleeping with a mortal warrior. The god learns of her infidelity from the crow (or raven), his sacred bird. Enraged, Apollo sends his sister, Artemis, to slay Coronis with arrows. But as the princess lies dead on her funeral pyre, Apollo regrets his wrath: He cuts his unborn son from his mother's womb. The baby grows up to be Asclepius, the hero-god of medicine, often identified as the constellation Ophiuchus, the Serpent-Bearer, who carries the snake-twined rod now commonly associated with doctors. To punish the loose-beaked crow, Apollo turns its white feathers black and then banishes it to the heavens. As further punishment, Apollo places the Water-Serpent constellation HYDRA to guard the stars of Crater, the sacred Cup, so that the crow can never slake its thirst. Coronis's Hydra means "crow," while Corvus means "raven." Thus, the constellation Corvus honors them both.

Excerpt from "The Immortals"

Reproduced with permission from Hachette Book Group. A full chapter excerpt is available at Olympus Bound.

After living for millennia without worship, Selene DiSilva no longer possesses the supernatural powers of Artemis, the goddess she once was. Like all the Athanatoi —Those Who Do Not Die — she has faded into a nearly mortal existence. Now, as a newly-revived ancient Greek cult murders virgin women in the streets of modern Manhattan, Selene finds her old powers suddenly revived. But she doesn't know why…

Selene opened the window wide and knelt before the sill, looking up at the sky above the rooftops. Even now, at the darkest hour before dawn, it shone with an unearthly glow.

Selene knew it was just light pollution bouncing off the clouds above, but sometimes she imagined the city possessed the sort of divine radiance once reserved for the gods. Just as in ancient times the Olympians had chosen to walk among mortals in disguise rather than reveal themselves in all their terrible glory, so New York clothed itself in dirt and noise and stench. Its true power would be too much for mortal eyes to bear.

"Imagine, Hippo," she said as the dog rested her chin on the windowsill. "Once I was the Lady of the Starry Host." She'd placed her victims in the heavens as eternal reminders of her rage and mercy. First Ursa Major—a nymph who broke her vows of chastity and was metamorphosed into a bear by Artemis's uncompromising justice. Then Ursa Minor—the son of that illicit union who met the same fate. "But now, even the strongest Athanatoi no longer possess the ability to make men into stars. Especially not here, where the stars themselves are hidden from view. New York's radiance outshines my own."

Over the centuries she'd watched the city's lights quench heaven's fire. With the constellations' disappearance, the history written in their outlines — her own history — dimmed alongside. She'd always imagined herself fading as well. Slowly, imperceptibly, disappearing into myth. But now, for the first time in an age, she felt hope.

She knew the most obvious explanation for her strengthening, and she didn't want to face it. She could barely admit it to herself. It was possible that her mother's decline was adding to her own strength. With one fewer god to siphon away the limited worship man still provided, the remaining Athanatoi might benefit.

Father, she prayed silently. Mighty Zeus, who once granted me six wishes, grant me one more. Help me find the answers I seek. Let my rebirth not come from my mother's death. And if you ever loved gentle Leto, help me save her. She closed her eyes and imagined her words reaching up to the vault of heaven, then soaring past the city, over the vast ocean, all the way to Zeus's lair on the island of Crete. And there the prayer died. Because her father could no longer hear.

Since the Diaspora, Zeus had lost his strength and his wits, eventually breaking his own vow of exile and returning to the Cave of Psychro, where he'd spent his infancy. In the nineteenth century, her half-brother Hermes had finally dared visit the Father of the Gods.

"By day, he looks up at the sky through the cave's mouth and watches the clouds pass," he told the Huntress afterward. "He waves his hands about as if he would bend the wind to his whim, and pouts when the sky doesn't obey. He's gone mad, Sister. There's moss in his hair and mold on his skin. By night, he crawls from the cave and raids the flocks of nearby farmers, eating sheep and goats raw. Mostly, though, he lives on bats and worms."

"Maybe that's all this is," Selene said to Hippo, rising to her feet and reaching for the bow leaning against the windowsill. "My own inevitable descent into madness." She twirled a shaft between her fingers before settling it against the arrow rest. "Maybe this is all a dream."

She sighted between the swaying branches of an oak over a hundred yards away on the border of the park, noting the skittering movement of a squirrel. It dashed down one branch then up another, hidden in the shadows of night. "Maybe I'm not going to make this shot," Selene said quietly. Then she loosed the arrow. A heartbeat later, the wind carried the faintest of squeals to the Huntress's ear. She lowered her bow. "For tonight, at least, I'm the Far Shooter. The Huntress. The Swiftly Bounding One. Go ahead," she said, looking down at Hippo. "Pick an epithet. I've got dozens."

The dog just cocked her head, oblivious.

For the first time in a long time, Selene wished she had a real friend. Can you see me, Orion? she wondered. Do you revel in my return to power — or dread it?

She looked up to where the scudding clouds left bare a patch of night sky and felt her triumph slip away. In a painful irony, the only stars bright enough to outshine the city lights were those that most tormented her. A star for each broad shoulder, a star for each strong leg, three stars slung in a glittering belt and a last for his sword. Cold, remote, a bare suggestion of a man, light years away from the one she'd known. Yet in the dark gaps of night, she saw strong limbs and fierce eyes, curling hair and a flashing smile. Orion, at once infinitely distant and just beyond reach, stared down like a reproachful judge upon the woman who'd loved him. The woman who'd killed him. The woman who'd placed him in the heavens as an eternal reminder of her guilt, her shame, her heartbreak.

Selene rose and moved to her narrow bed. She thought suddenly of Theodore Schultz. He too had lost someone he loved. But in every photo, friends surrounded him, smiling, laughing, touching. He would grieve, but — unlike Selene — he would not be alone.

She fell asleep with the wind streaming across her face from the open window. For the first time in centuries, she dreamed Orion was with her. He smelled like the dry hills of Attica. Like oregano crushed underfoot. Like sweat and heat and the thrill of the chase. His warm flesh pressed against her back. His fingertips traced a line of fire up her arm, to her neck, where his lips, rough and wind burnt, pressed a kiss into the hollow of her ear.

With the frenzy of a drowning woman, Selene pulled herself from the dream and sat up, sure Orion was there. She imagined she could still smell him on the wind. But dawn reddened the sky, the stars had been put to flight, and she was alone.

Follow all of the Expert Voices issues and debates — and become part of the discussion — on Facebook, Twitter and Google+. The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the publisher. This version of the article was originally published on Space.com.