'The Second World' shows how humanity makes mistakes in futuristic society

Jake Korell’s debut novel 'The Second World' envisions a newly independent Mars shaped by real space-policy debates, near-future technology, and the very human absurdities we’ll bring with us when we leave Earth.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

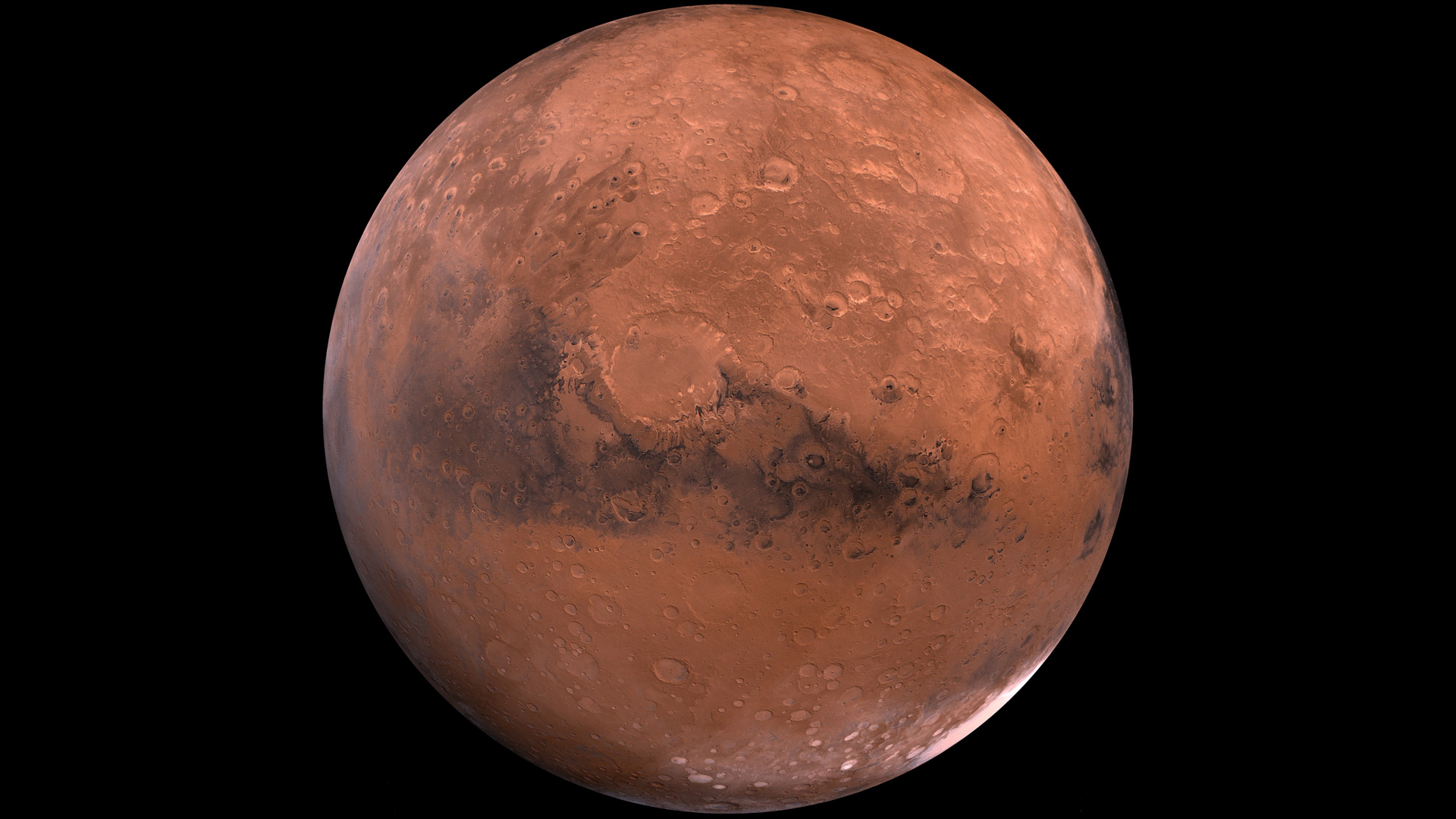

What happens when humanity finally builds a civilization on another planet, and immediately repeats its old mistakes? That question drives 'The Second World', the sharp, satirical debut from writer Jake Korell. Set against the rise of a breakaway Martian nation, the story follows Flip Buchanan, son of the colony’s most powerful leader, as he navigates two chaotic decades of scientific breakthroughs, political theater, and cultural growing pains on the Red Planet.

Korell grounds his humor in real near-future science. His Mars isn't a distant fantasy but a logical extension of the conversations happening right now in space exploration, from private-sector expansion to the ethics of off-world settlement. By keeping the technology plausible and the human behavior all too familiar, Korell creates a world that feels both futuristic and uncomfortably recognizable.

The result is a story that treats space exploration seriously while embracing the absurdity of human nature. Blending the scientific accessibility of Andy Weir with the satirical edge of Vonnegut, Korell imagines a Mars shaped as much by physics as by politics, ego, and ambition.

In our Q&A below, he discusses the science, the satire, and the real policy debates that inspired 'The Second World,' which is available in Feburary 2026.

Space: 'The Second World' uses Mars as both a literal and symbolic frontier. What drew you to Mars specifically, and how did you balance real space-science plausibility with satire and speculative fiction?

Korell: I've always loved anything related to outer space. It activates the farthest reaches of our imagination—the vastness, the weird physics, the unknown. The future has that same built-in sense of wonder, the same limitless possibilities. But in storytelling, if you push too far ahead or veer too far away from what we've actually observed in the universe, things can become abstract and less relatable. A near-future Mars felt like the perfect middle ground, especially since people are already making plans to colonize. It's a whole other planet, but still our next-door neighbor—relatively speaking. Building a world on the Red Planet gave me immense creative freedom while keeping everything tethered to our own experience...

My goal was to keep the world scientifically plausible, then bend it just enough to make it funny. Something that might sound absurd to us now, but would feel completely normal to the characters living in that reality.

Space.com: Your story imagines a newly sovereign Martian nation grappling with political identity, culture, and legacy. How did real conversations in space policy, colonization ethics, and planetary nationalism influence your worldbuilding?

Korell: Worldbuilding has always been my favorite part of the writing process, and I love taking real issues from our world and weaving them into a place that’s entirely invented. When you start looking at space policy and colonization ethics, you realize how unsettled everything still is. No one "owns" Mars or the Moon. Even on Earth, we have borders and land because we say so, and the authority only comes from the ability to enforce it. Things are more nuanced now, but that’s still the foundation everything rests on. And in early America, colonizers took land from Native peoples simply because they could.

My Mars colony quickly emerged as the perfect allegory for the thirteen colonies, and the void between planets just became a much, much bigger Atlantic Ocean. The pattern was familiar. In colonization, first come the explorers, then the investors, then the politicians. A SpaceX-like corporation will almost certainly reach Mars first—acting as both explorer and investor, in this case. And the eventual Martian independence movement will be more like a corporate revolution. A union strike in spacesuits. But it’s all the same pattern, just with different branding...

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Space.com: The book spans decades of technological and societal evolution on Mars. What future tech, space-travel concepts, or colonization challenges did you feel were essential to ground the story in believable near-future science?

Korell: Twenty years is a long span to cover, and technology can change dramatically in that window. That's part of why I grounded the story more in the characters than the gadgets. Human behavior is the one constant. If the people feel real, the future around them can stretch a little without breaking.

I also didn't want to bury the story under pages of scientific exposition. It’s harder to land a joke between equations and formulas. The future tech used in the story is based on ideas already theorized in scientific and sci-fi circles: holograms, space elevators, VR, alien contact, cloning, even faster-than-light travel through a spacetime distortion bubble. I certainly bent some rules and twisted others, but the foundation is always something plausible within speculative science.

Throughout the book, I poke fun at certain technologies, but I'm really satirizing the sci-fi storytelling tropes more than the science itself. The first Mars colony certainly won't be a giant glass-dome biosphere, but it’s such a classic visual that it carries a kind of cultural shorthand. Using these sorts of things allows the reader to orient themselves quickly so the satire and story can take center stage.

Space.com: Many sci-fi works treat Mars as humanity's escape hatch — a fresh start. In 'The Second World', we bring our flaws with us. What do you think is the most realistic obstacle preventing humanity from building a better world in space?

Human nature—specifically greed—is the biggest obstacle. We can take humans off Earth, but we're still bringing our instincts, anxieties, and ambitions with us. You can't code that out of a species.

But my view isn't totally pessimistic. If you look at history, we've improved ourselves quite a bit, little by little. Focusing specifically on the United States, putting politics aside, most of us can agree that the Founding Fathers creating a democracy was a major step up from living under a monarchy. And we've been refining and adjusting ever since. Mistakes were made, and continue to be made. It’s not perfect. And most likely, no futuristic space society will be either. But we're improving.

Progress requires a marketplace of ideas. And for that to exist, people can't all be cut from the same cloth. Diversity of thought brings innovation… along with bad actors, dumb ideas, and the occasional catastrophic oopsie. You get the full spectrum. You have to take the good with the bad.

The "bad" in that equation is almost always greed. If the incentives in space aren't aligned with building a better world, if profit outweighs purpose, we won't suddenly become enlightened just because we’re on a new planet. Whether it's Earth, Mars, or some asteroid we're mining, the challenge is the same: if the money doesn't point us toward a utopia in space, it's not going to happen.

Space.com: Your influences range from grounded sci-fi voices like Andy Weir to more absurdist storytellers. How do you approach blending scientific realism, speculative imagination, and humor while still respecting the seriousness of space exploration?

...I fully believe that a space settlement is inevitable. Humans have always been explorers, searching for better places, better materials, better systems—in other words, progress. Throughout history, people have fought progress, but they always lose. The people who invested in horse-drawn carriages weren't thrilled about automobiles, but cars weren't going to disappear just to protect the carriage-industrial complex. There was a much more lucrative automobile-industrial complex to consider. In the same way, settling Mars isn't hypothetical. It's in motion. People are actively working toward it right now. And once we settle Mars, we'll look to the moons of Jupiter or Saturn. After that, we'll start eyeing planets outside our solar system. It’s just a matter of time horizon.

You can follow Jake Korell's work on TikTok or Instagram.

Kenna Hughes-Castleberry is the Content Manager at Space.com. Formerly, she was the Science Communicator at JILA, a physics research institute. Kenna is also a freelance science journalist. Her beats include quantum technology, AI, animal intelligence, corvids, and cephalopods.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.