'Meteor Storm' May Light Up Friday Night Sky

As Earth orbits the sun, the planet constantly sweeps up interplanetary debris. This debris often heats the Earth's upper atmosphere until it glows, leaving brief trails across the night sky that people once called "shooting stars" or "falling stars."

This weekend, stargazers in North America could get a glimpse of many of these objects, which are now known as meteors.

Mostly, the Earth hits these meteors at random, so you can never be sure when or where you will see a meteor. But sometimes the Earth passes through denser clouds of particles, and the meteors are brighter and more frequent, producing what are called "meteor showers." [New Meteor Shower from Comet 209P/LINEAR (Gallery)]

Most of these debris fields are leftovers from periodic comets. As these comets make repeated visits to the inner solar system, they gradually shed material, which gets spread along their orbits. When Earth passes through one of these cometary ghosts, the planet gets an increased number of meteors.

Just such a comet has set up the upcoming meteor shower. A rather unimpressive comet with the unromantic name of 209P/LINEAR will make a close approach to Earth on May 29, passing a mere 5 million miles (8 million kilometers) away. Five days before the comet's closest approach, Earth will pass through the object's orbit, and some astronomers predict a major new meteor shower for that night.

Comet orbits are very precisely known, and astronomers predict Earth will pass through 209P's debris field between 3 a.m. and 4 a.m. EDT (0700 and 0800 GMT) on Saturday morning, May 24. Further west, the time will be earlier, between midnight and 1 a.m. PDT on the West Coast.

Many people get confused about astronomical events that happen after midnight, forgetting that the date changes at midnight. So this meteor shower will occur after midnight on Friday night, May 23, which is Saturday morning, May 24. So don't wait until Saturday night to look for it, or you will be 24 hours late.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Meteors are not rare events. The only reason most people rarely see them is that most individuals don't look at the sky long enough or often enough, or they look at a sky full of light pollution, which hides the faint meteors. On an average night at any time in the year, anyone who stares at the sky after midnight for an hour should see about half a dozen meteors.

During a meteor shower, the number of meteors seen in an hour might increase by two to three times. But again, unless you make an effort to watch, you won't see many.

Often, when people read about a meteor shower, they actually expect what astronomers call a meteor storm. During one of these events, hundreds of meteors appear, filling the sky with celestial fireworks. However, such meteor storms are exceedingly rare, perhaps three or four per century.

There is a chance, a very small chance, that a meteor storm might occur this weekend, and this has astronomers very excited.

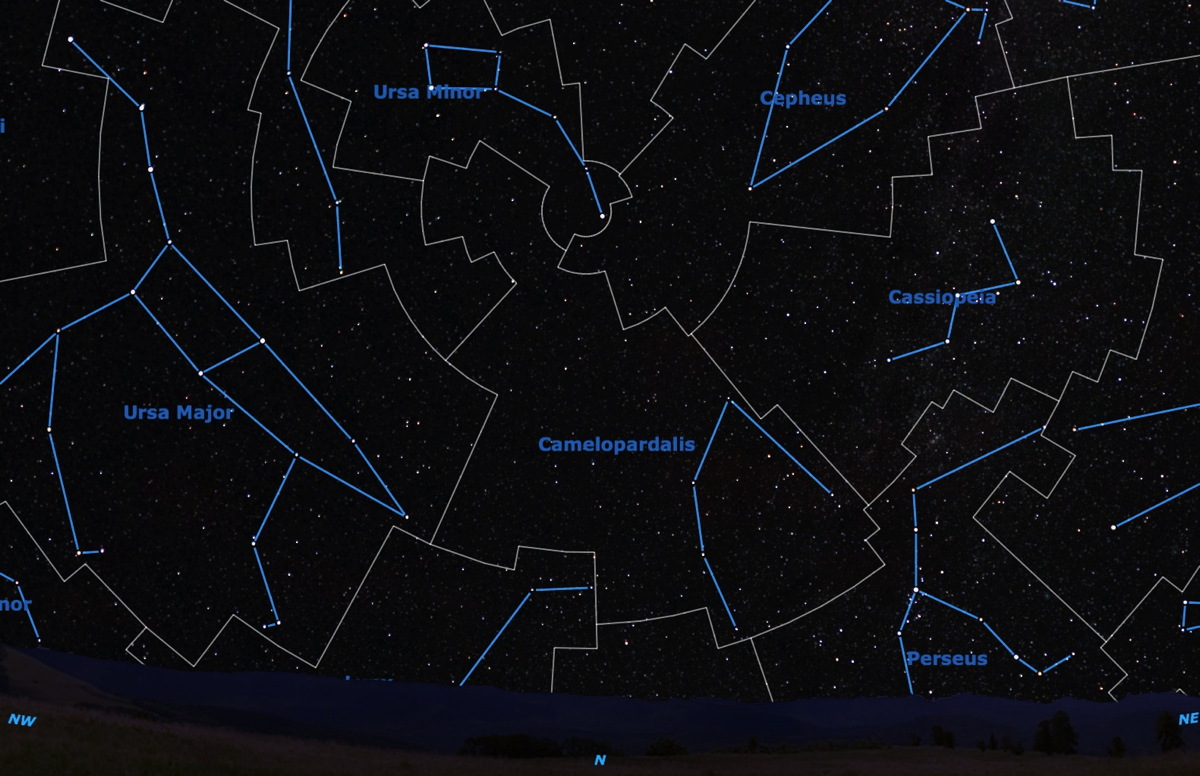

One of the most frequent questions about meteor showers is, "Where should I look?" The answer is that it really doesn't matter, because meteors can appear anywhere in the sky. Although all the meteors in a shower appear to radiate from a particular point in the sky, called the radiant, this is not the best direction to look, as the meteors close to the radiant tend to be quite short in length. I prefer to look about 90 degrees away from the radiant, where the meteors will tend to be longest.

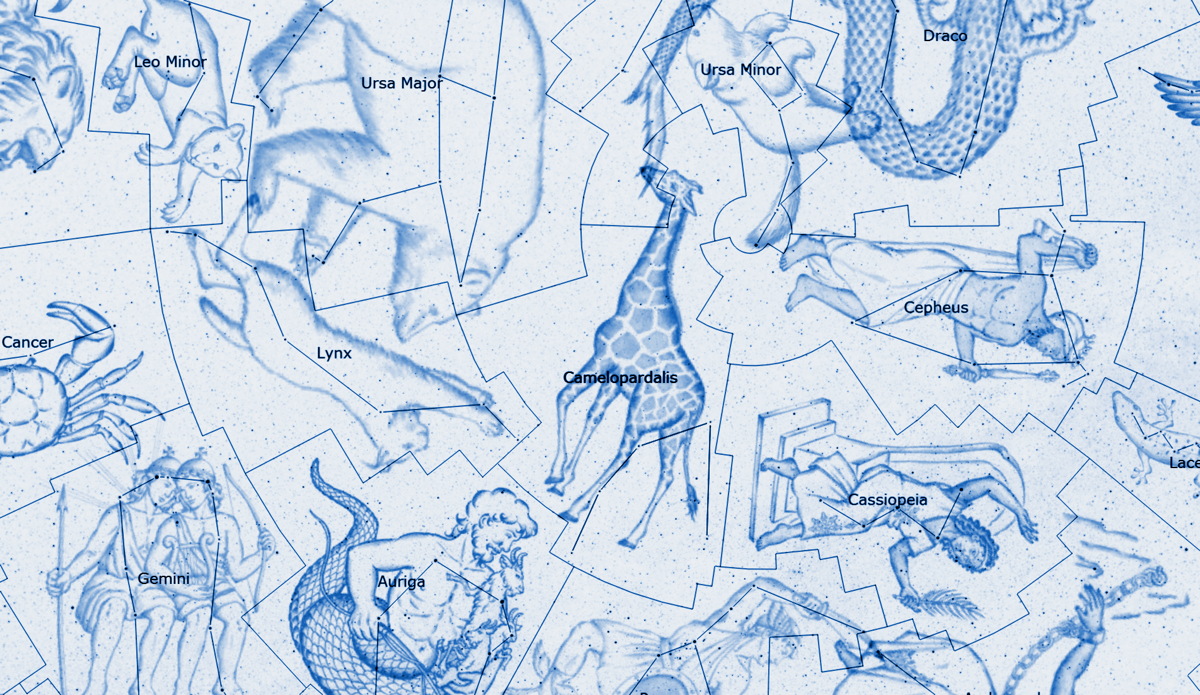

The radiant for this shower will be in the dim and little-known constellation of Camelopardalis, the Giraffe. This is about halfway between Ursa Major (the Big Dipper) and Cassiopeia, right under Polaris, the Pole Star.

Having said all that, let me be honest with you: Comets and meteor showers are notoriously unpredictable. There is a very good chance that absolutely nothing will be visible on Saturday morning. But you can bet that every serious astronomer in North America will be out looking, just in case.

This article was provided to Space.com bySimulation Curriculum, the leader in space science curriculum solutions and the makers of Starry Night and SkySafari. Follow Starry Night on Twitter @StarryNightEdu. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Geoff Gaherty was Space.com's Night Sky columnist and in partnership with Starry Night software and a dedicated amateur astronomer who sought to share the wonders of the night sky with the world. Based in Canada, Geoff studied mathematics and physics at McGill University and earned a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Toronto, all while pursuing a passion for the night sky and serving as an astronomy communicator. He credited a partial solar eclipse observed in 1946 (at age 5) and his 1957 sighting of the Comet Arend-Roland as a teenager for sparking his interest in amateur astronomy. In 2008, Geoff won the Chant Medal from the Royal Astronomical Society of Canada, an award given to a Canadian amateur astronomer in recognition of their lifetime achievements. Sadly, Geoff passed away July 7, 2016 due to complications from a kidney transplant, but his legacy continues at Starry Night.