Prehistoric Paint to Shield European Sun Probe from Solar Inferno

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

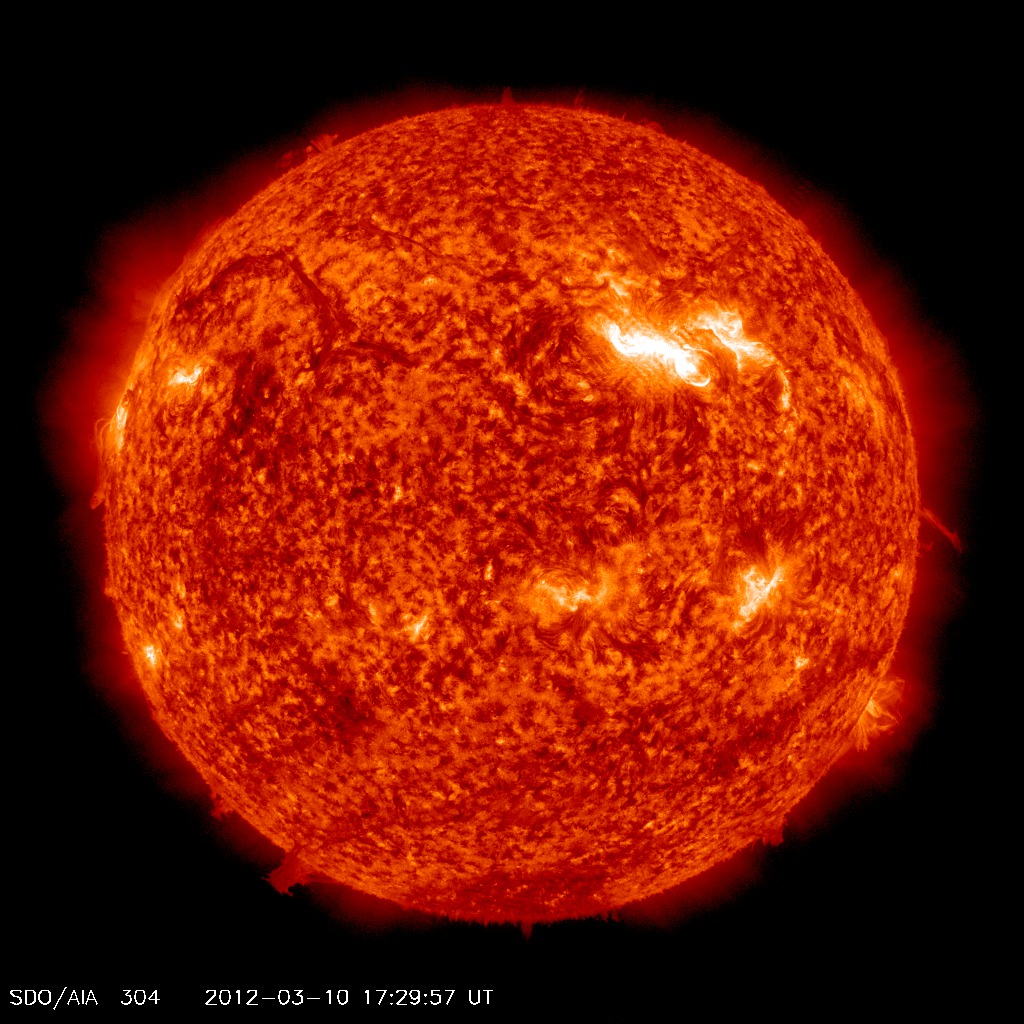

A European spacecraft set to launch toward the sun in 2017 will be protected by a paint once used in prehistoric cave art.

The European Space Agency's Solar Orbiter probe will be coated in a substance derived from burnt bone charcoal — a type of pigment once used by early humans to create art on the insides of caves in France. The robust substance traditionally made from burned bones should help protect the Solar Orbiter when it flies as closer to the sun than any spacecraft before it.

The probe will fly about 26 million miles (42 million kilometers) from the sun, a bit more than a quarter of the distance from Earth to the star. The Earth is about 93 million miles (150 million km) from the sun on average. Mercury, the closest planet to the sun, approaches within 28.5 million miles (48.8 million km) at its closest point to the star. [The Sun's Wrath: The Worst Solar Storms in History]

While observing the sun from space, the Solar Orbiter will have to face temperatures up to 968 degrees Fahrenheit (520 degrees Celsius), ESA officials said. Scientists working with the spacecraft realized that they needed to re-work the heat shield when they ruled out their initial choice to use a carbon fiber fabric in 2010, they added.

'We soon identified a problem with the heat shield requirements," Andrew Norman, a materials technology specialist, said in an ESA statement. "To go on absorbing sunlight, then convert it into infrared to radiate back out to space, its surface material needs to maintain constant 'thermo-optical properties' — keep the same color despite years of exposure to extreme ultraviolet radiation.

"At the same time, the shield cannot shed material or outgas vapor, because of the risk of contaminating Solar Orbiter’s highly sensitive instruments," Norman added. "And it has to avoid any build-up of static charge in the solar wind because that might threaten a disruptive or even destructive discharge."

"The big advantage is that the new layer ends up bonded, rather than only painted or stuck on," John O'Donoghue, Managing Director of Enbio, said of the Solar Black material in a statement. "It effectively becomes part of the metal — when you handle metal you never worry about its surface coming off in your hands."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

ESA engineers are planning to test Solar Black-treated titanium to see how it will hold up in a vacuum chamber that will simulate some of the environments the spacecraft could encounter while observing the sun.

Follow Miriam Kramer @mirikramer and Google+. Follow us @Spacedotcom, Facebook and Google+. Original article on Space.com.

Miriam Kramer joined Space.com as a Staff Writer in December 2012. Since then, she has floated in weightlessness on a zero-gravity flight, felt the pull of 4-Gs in a trainer aircraft and watched rockets soar into space from Florida and Virginia. She also served as Space.com's lead space entertainment reporter, and enjoys all aspects of space news, astronomy and commercial spaceflight. Miriam has also presented space stories during live interviews with Fox News and other TV and radio outlets. She originally hails from Knoxville, Tennessee where she and her family would take trips to dark spots on the outskirts of town to watch meteor showers every year. She loves to travel and one day hopes to see the northern lights in person. Miriam is currently a space reporter with Axios, writing the Axios Space newsletter. You can follow Miriam on Twitter.