'The beacons were lit!' Scientists name merging supermassive black holes after 'Lord of the Rings' locations

"Rohan was first, for Rohan Shivakumar, the Yale student who first analyzed it, and Gondor was next, because, well — the beacons were lit!"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

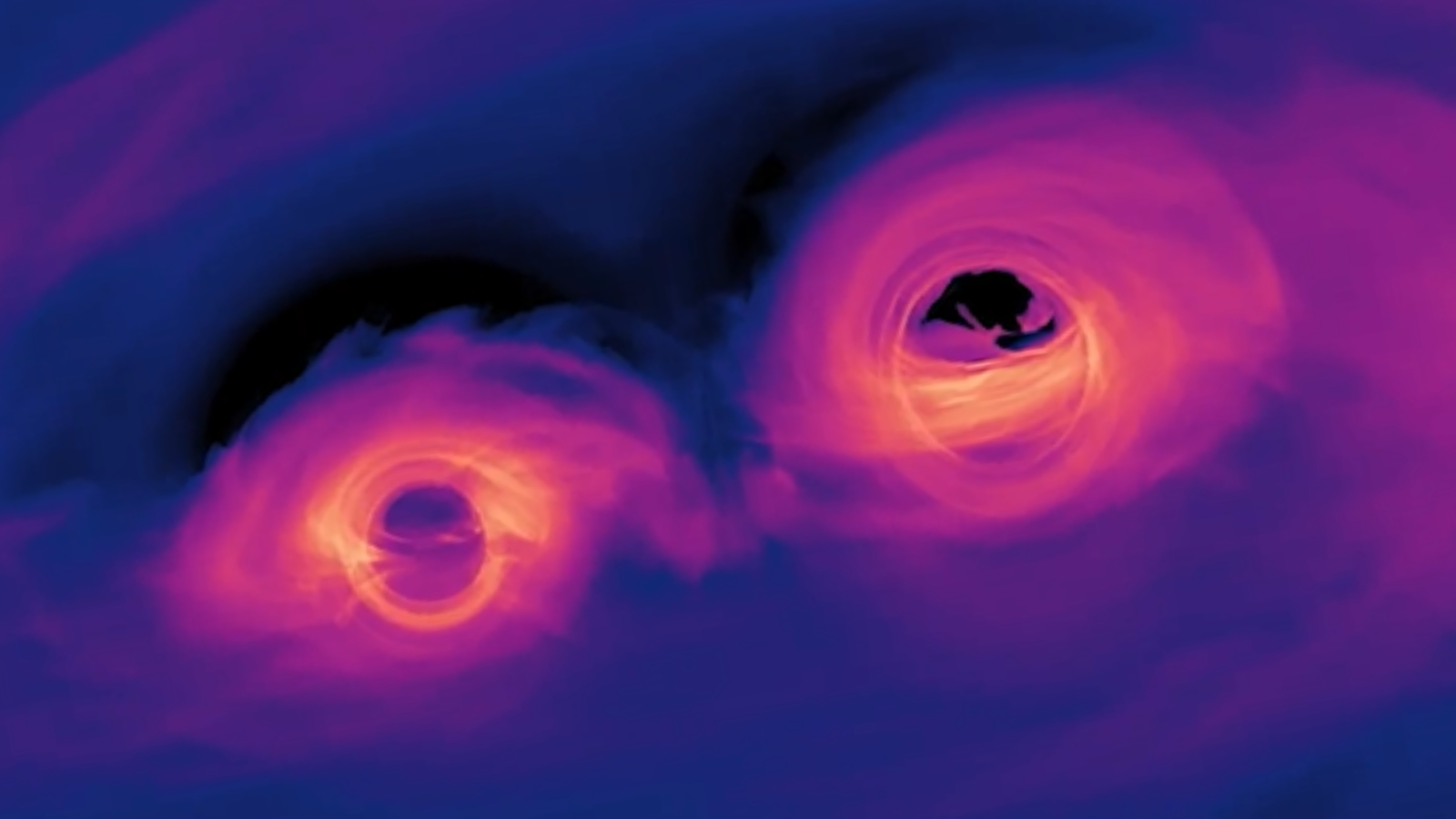

When the beacons were lit in "The Lord of the Rings: The Return of the King," the city of Gondor called to Rohan for aid, spelling doom for Sauron and his legions. However, when the beacons of supermassive black hole systems named for these locations in J.R.R. Tolkien's "Lord of the Rings" novels were lit up, it was exceptionally good news for scientists.

The supermassive black hole binaries Gondor, officially designated SDSS J0729+4008, and Rohan, SDSS J1536+0411, were discovered by the North American Nanohertz Observatory for Gravitational Waves (NANOGrav) using a new technique that uses the background hum of ripples in space called "gravitational waves" in conjunction with observations of quasars, which are powered by feeding supermassive black holes.

The logic behind this is that supermassive black hole binaries, which spiral together to lead to collisions and mergers, emit gravitational waves of increasing frequency as their orbits shrink, creating a background hum of gravitational waves. The resultant mergers seem to be five times more likely to be found in quasars.

Article continues below

That makes quasars beacons that can indicate the unification of supermassive black holes. If one of these beacons radiates gravitational waves like the lit beacons of Gondor, it indicates binary black holes are present. Thus, this detection technique offers scientists a method to create a cosmic map of these merging titans.

"Our finding provides the scientific community with the first concrete benchmarks for developing and testing detection protocols for individual, continuous gravitational wave sources," NANOGrav team member Chiara Mingarelli said in a statement.

Mingarelli and colleagues hunted for supermassive black hole binaries using their new approach in 114 Active Galactic Nuclei (AGNs), the bright central regions of galaxies where supermassive black holes are ravenously feasting on surrounding gas and dust.

Mingarelli explained the reason for the unusual name choice for these black hole systems: "The names come from both people and pop culture. Rohan was first, for Rohan Shivakumar, the Yale student who first analyzed it, and Gondor was next, because, well — the beacons were lit!"

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

NANOGrav, which first detected a gravitational wave background in 2023, will spend the coming months hunting and identifying supermassive black hole binaries. The team thinks that even a relatively small catalog of black hole mergers could help create a gravitational wave background map. This research could also help scientists better understand galaxy mergers, the physics of black holes and the nature of gravitational waves themselves.

"Our work has laid out a roadmap for a systemic supermassive black hole binary detection framework," Mingarelli said. "We carried out a systematic, targeted search, developed a rigorous protocol — and two targets rose to the top as examples motivating follow-up."

The team's results were published on Feb. 5 in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Robert Lea is a science journalist in the U.K. whose articles have been published in Physics World, New Scientist, Astronomy Magazine, All About Space, Newsweek and ZME Science. He also writes about science communication for Elsevier and the European Journal of Physics. Rob holds a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy from the U.K.’s Open University. Follow him on Twitter @sciencef1rst.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.