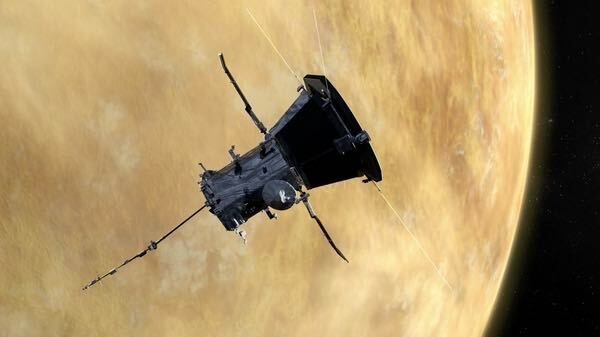

NASA's Parker Solar Probe to make closest flyby of Venus on Aug. 21

If all goes well, the spacecraft will soon be headed even closer to the sun.

Since 2021, NASA's Parker Solar Probe has been treading impressively close to the sun in order to capture unprecedented data about our home star.

In fact, the record-breaking spacecraft completed its closest approach yet to the blazing ball of plasma in June, coming within just 5.3 million miles (8.3 million kilometers) of the solar surface. To reach these incredible milestones, Parker gets by with a little help from its friends. Well, one friend: Venus.

NASA says Parker is on track to make its sixth and closest flyby of Venus on Aug. 21, thanks to some precise maneuvering that took place on Aug. 3. The goal is for the probe to use the amber-hued planet's gravity to tighten its orbit around the sun — a technique Parker has been employing repeatedly during its mission, which began with a launch on Aug. 12, 2018. If all goes well with this Venusian approach, Parker will come within about 4.5 million miles (7.2 million km) of the solar surface on Sept. 27.

But the story won't end there.

NASA has one more Venus flyby planned after this one, which is designed to sling Parker to within just 3.9 million miles (6.2 million km) of the sun. For context, Earth sits about 93 million miles (149 million km) from that shining yellow orb. So, Parker's going to get really, really close.

Related: NASA's Parker Solar Probe starts summer with 16th swoop by the sun

To delve into some technical details, Parker's recent maneuvering consisted of the craft firing its small thrusters for 4.5 seconds in order to adjust its trajectory by 77 miles (124 kilometers) and increase its speed by 1.4 seconds while heading to Venus. These shifts are actually quite minute considering the probe has been traveling at hundreds of thousands of miles per hour while flying through the inner solar system.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

During September's upcoming solar approach, for instance, the team says Parker will be moving at 394,742 mph (635,276 kph) — a new speed record for the probe and for spacecraft in general. And at its closest approach ever, it's expected that Parker will zoom through space at about 430,000 mph (700,000 kph) — a velocity NASA says would be fast enough to get you from Philadelphia to Washington, D.C. in one single second.

"Parker’s velocity is about 8.7 miles per second, so in terms of changing the spacecraft’s speed and direction, this trajectory correction maneuver may seem insignificant," Yanping Guo, mission design and navigation manager at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory in Maryland, said in a statement. "However, the maneuver is critical to get us the desired gravity assist at Venus, which will significantly change Parker’s speed and distance to the sun."

Since its launch in 2018, Parker has been dubbed the probe that'll "touch the sun." And that it did. In 2021, it finally flew through our star's upper atmosphere, otherwise known as the corona, which officially meant it truly "touched the sun."

With Parker's data, scientists hope to answer several big questions about our star, such as why the corona is so much hotter than the surface – what a weird conundrum – and decode the ins and outs of the stream of charged particles known as the solar wind. And, that's just the beginning. Eventually, perhaps it'll solve a few riddles we didn't quite know we should be pondering.

After all, it was only recently when scientists found the sun blasting out the highest-energy radiation ever recorded, suggesting that we just may not have this star figured out yet.

Monisha Ravisetti is Space.com's Astronomy Editor. She covers black holes, star explosions, gravitational waves, exoplanet discoveries and other enigmas hidden across the fabric of space and time. Previously, she was a science writer at CNET, and before that, reported for The Academic Times. Prior to becoming a writer, she was an immunology researcher at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York. She graduated from New York University in 2018 with a B.A. in philosophy, physics and chemistry. She spends too much time playing online chess. Her favorite planet is Earth.