2 Earth weather satellites accidentally spy on Venus

"We believe that continuing such activities will further expand our horizon in the field of planetary science."

In a serendipitous turn of events, scientists have discovered that Japan's Himawari-8 and Himawari-9 weather satellites, designed to monitor storms and climate patterns here on Earth, have also been quietly collecting valuable data on Venus for nearly a decade.

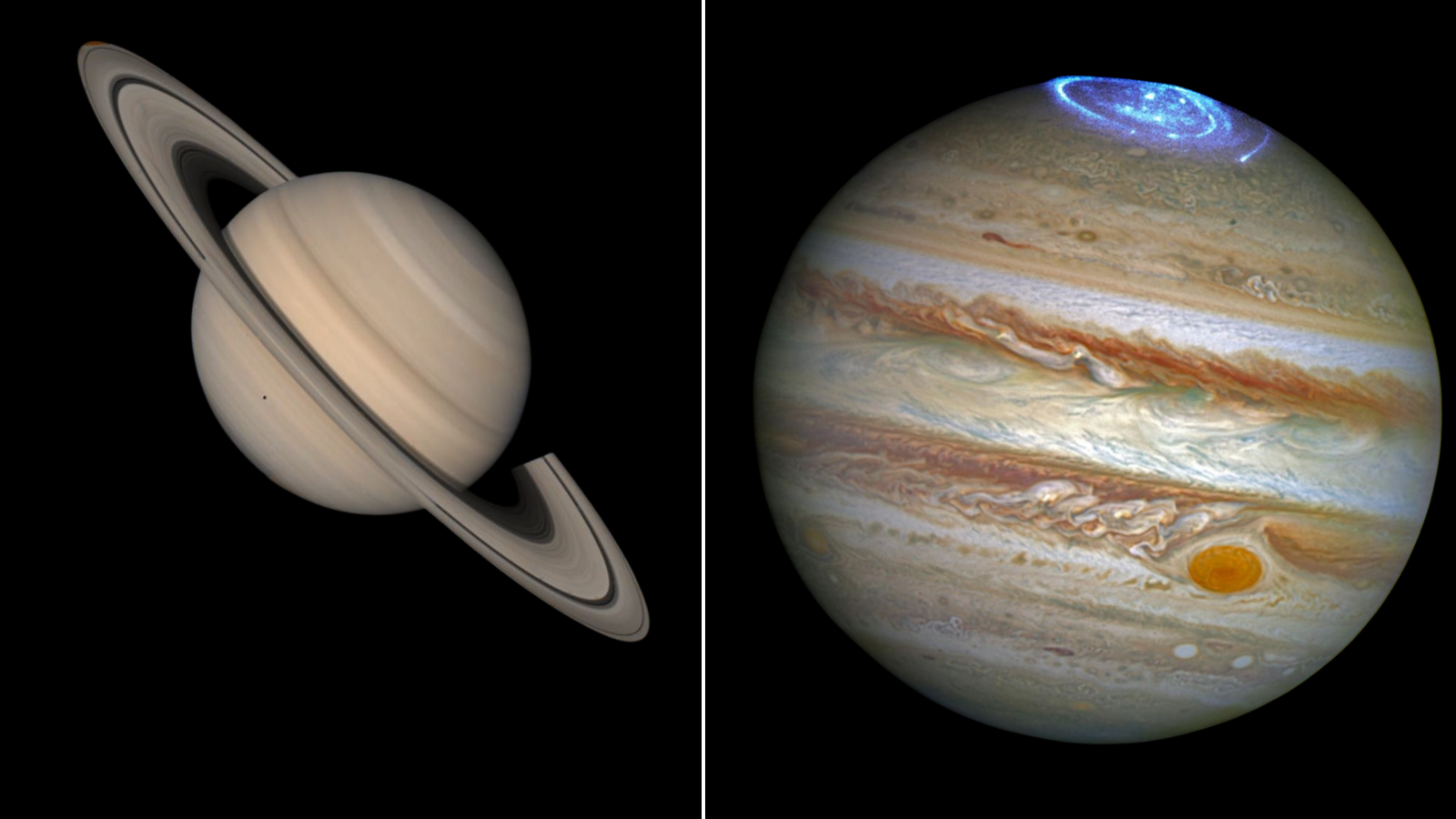

Although meteorological satellites orbit Earth and scan the skies around it, their imaging range extends into space, allowing them to occasionally catch glimpses of other celestial neighbors, such as the moon, stars and other planets in our solar system.

"This started by chance," explained Gaku Nishiyama, a postdoctoral researcher at the German Aerospace Center (known by its German acronym, DLR) in Berlin in an interview with Space.com. "One of my best friends, who has a Ph.D. in astronomy and is a certified weather forecaster in Japan, found lunar images in Himawari-8/9 datasets and asked me to look."

At the time, Nishiyama was focused on lunar science, and he began using the Himawari-8 and Himawari-9 weather satellites — which launched in 2014 and 2016, respectively — in an unconventional way: as space telescopes. By analyzing the light the moon emitted in infrared wavelengths, he and his team were able to test the satellites' ability to capture temperature variations across the moon's surface as well as determine its physical properties.

"During this lunar work, we also found other solar-system bodies, namely Mercury, Venus, Mars, and Jupiter, in the datasets. We were interested in what phenomena were recorded there," Nishiyama explained.

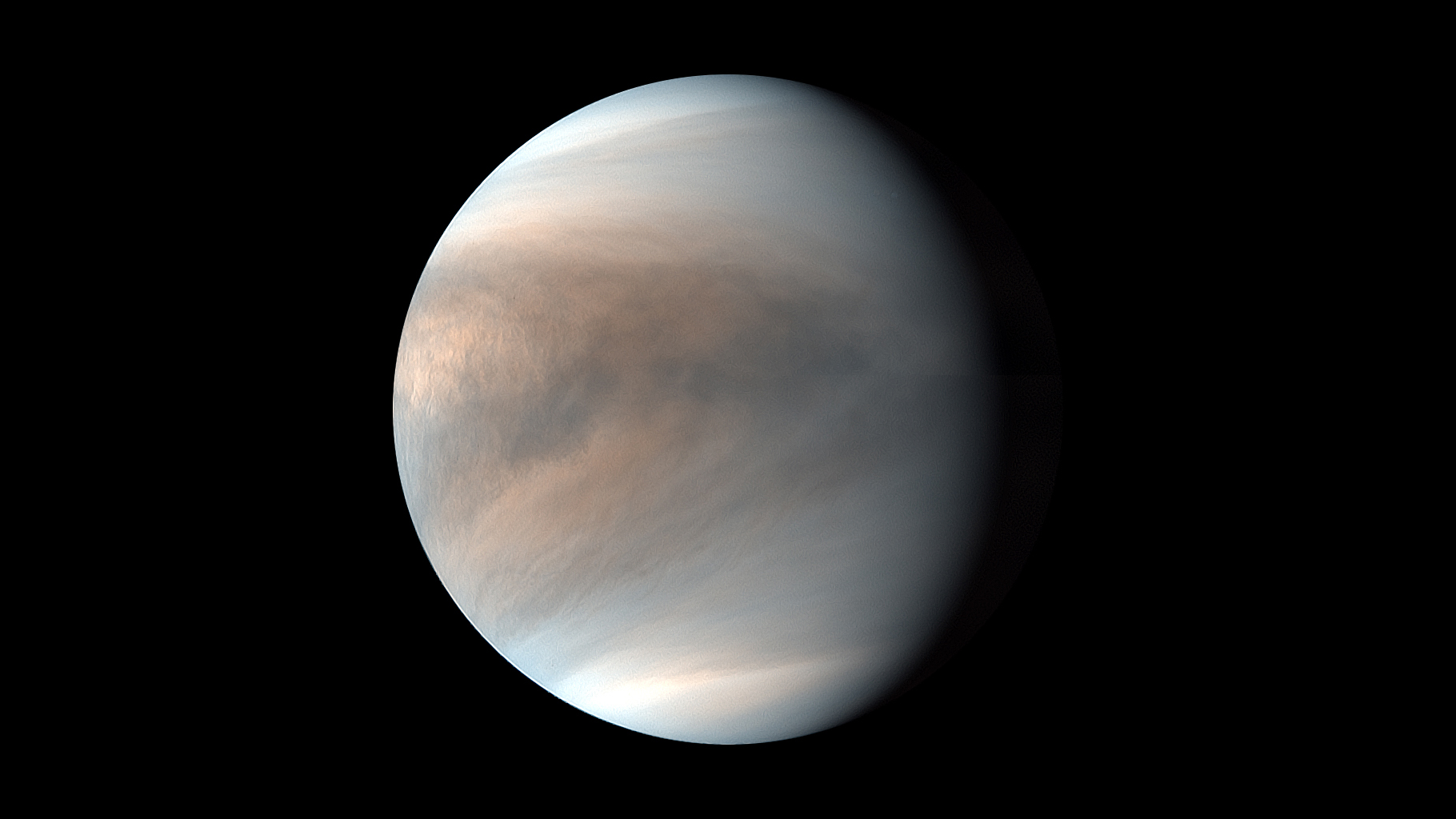

To spot Venus in the Himawari data, the team used the precise imaging schedule and position of the satellites. "Because we know almost exactly when and where Himawari is looking," Nishiyama said, "we can roughly predict where Venus will appear in each image. From there, we isolate the pixels corresponding to Venus."

Nishiyama and his colleagues were analyzing subtle changes in the intensity of light Venus was emitting. Such data allows scientists to track how a celestial body's brightness varies over time, which in turn reveals details about it.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The Himawari satellites ended up capturing one of the longest multiband infrared records of Venus ever assembled. This unique dataset revealed subtle, year-to-year changes in the planet's cloud-top temperatures, as well as signs of phenomena called thermal tides and Rossby waves.

"Thermal tides are global-scale gravity waves excited by solar heating in the cloud layers of Venus," Nishiyama explained. "When the atmosphere is stratified, like on Venus (i.e., a warm upper layer atop a cold lower layer), a restoring force acts upon heated air parcels, and the resulting vertical oscillations propagate as gravity waves. Rossby waves [also seen in Earth's oceans and atmosphere] are also a global-scale wave caused by variations in the Coriolis force with latitude.

"Both types of waves are crucial for transporting heat and momentum through Venus' atmosphere," he continued. "Tracking how these waves change over time helps us better understand the planet's atmospheric dynamics, especially since other data, like wind speeds and cloud reflectivity, have shown variations that play out over several years.

"Specifically, we succeeded in detecting variations in temperature fields caused by Rossby waves at various altitudes for the first time, which is important to understanding the physics behind the years-scale variation of the Venus atmosphere," said Nishiyama.

These new observations help fill a crucial gap in our understanding of Venus' dynamic upper atmosphere and open a new frontier in planetary monitoring from Earth orbit. The team's findings also challenge the calibration of key instruments on dedicated Venus spacecraft, like the LIR camera aboard Japan's Akatsuki Venus orbiter.

"To understand the atmospheric structure of Venus, determination of temperature at infrared wavelengths is crucial," said Nishiyama. "LIR was expected to provide accurate temperature information; however, LIR has faced several issues in instrument calibration."

Comparing images taken by LIR and Himawari satellites at the same time and under identical geometric conditions, the team found discrepancies and suspects that LIR may be underestimating Venus' radiance. "Our comparison between Himawari and LIR sheds light on how to recalibrate the LIR data, leading to a more accurate understanding of Venus' atmosphere," Nishiyama said.

The team is also hopeful that Himawari will complement data from missions such as Akatsuki and BepiColombo, a joint Japanese-European mission that's currently establishing itself in orbit around Mercury. Nishiyama explained that, compared to Akatsuki, Himawari covers a wider range of infrared wavelengths and provides information across various altitudes. In contrast to BepiColombo, which observed Venus only during a flyby, Himawari can monitor the planet over a much longer timescale.

"Earth-observing satellites [like Himawari] are generally calibrated so accurately that they can provide reference data for instrument calibrations in future planetary missions," he said. "Unlike meteorological observation on the Earth, there are often time gaps between planetary missions. Since meteorological satellites continue observation from space for decadal timescales, these satellites can supplement data even when there are no planetary exploration spacecraft orbiting around planets."

Nishiyama said that the team has already archived other solar-system bodies, which are now being analyzed. "We believe that continuing such activities will further expand our horizon in the field of planetary science," he concluded.

The team reported their findings last month in the journal Earth, Planets and Space.

A chemist turned science writer, Victoria Corless completed her Ph.D. in organic synthesis at the University of Toronto and, ever the cliché, realized lab work was not something she wanted to do for the rest of her days. After dabbling in science writing and a brief stint as a medical writer, Victoria joined Wiley’s Advanced Science News where she works as an editor and writer. On the side, she freelances for various outlets, including Research2Reality and Chemistry World.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.