A failed Soviet Venus probe from the '70s crashed to Earth in May — why was it so hard to track?

"Being off even a little bit represents hundreds or thousands of kilometers in distance on the surface of the Earth."

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered daily

Daily Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

Once a month

Watch This Space

Sign up to our monthly entertainment newsletter to keep up with all our coverage of the latest sci-fi and space movies, tv shows, games and books.

Once a week

Night Sky This Week

Discover this week's must-see night sky events, moon phases, and stunning astrophotos. Sign up for our skywatching newsletter and explore the universe with us!

Twice a month

Strange New Words

Space.com's Sci-Fi Reader's Club. Read a sci-fi short story every month and join a virtual community of fellow science fiction fans!

The recent fall to Earth of a failed Soviet Venus probe from the 1970s has become a detective story of sorts.

Different computer models were used to predict the reentry. But why were they divergent, and how can we improve our ability to nail down the "whereabouts and when" as a space object crashes into Earth's atmosphere?

The long and troubled history of the would-be Venus spacecraft, known as Kosmos-482, can shed some light on these key questions, scientists say. So, let's have a look.

Down and out

On May 10 of this year, the egg-shaped Kosmos-482 descent module, weighing roughly 1,091 pounds (495 kilograms), likely fell into ocean waters.

According to calculations by specialists from TsNIIMash, part of the Russian space agency Roscosmos, the spacecraft entered the dense layers of the atmosphere and fell into the Indian Ocean west of Jakarta.

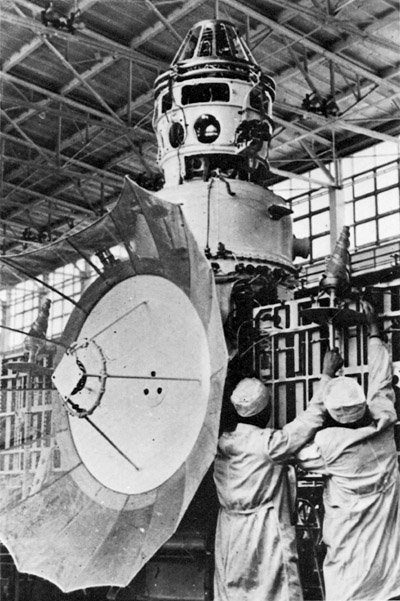

The hardware was lofted in the spring of 1972 to study Venus, but due to a malfunction of its rocket's upper stage, it remained in a high elliptical orbit around Earth, gradually closing in on our planet.

The probe was one of a pair of Venus atmospheric landers hurled skyward during their respective go-to-Venus launch windows.

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

The twin Venera-8 spacecraft was launched a few days earlier, sent onward to become the first station to land on the illuminated side of Venus, successfully transmitting data on temperature and pressure from the planet's surface.

Lost in space

Meanwhile, the botched probe that failed to get from Earth to Venus was "renamed" Kosmos-482.

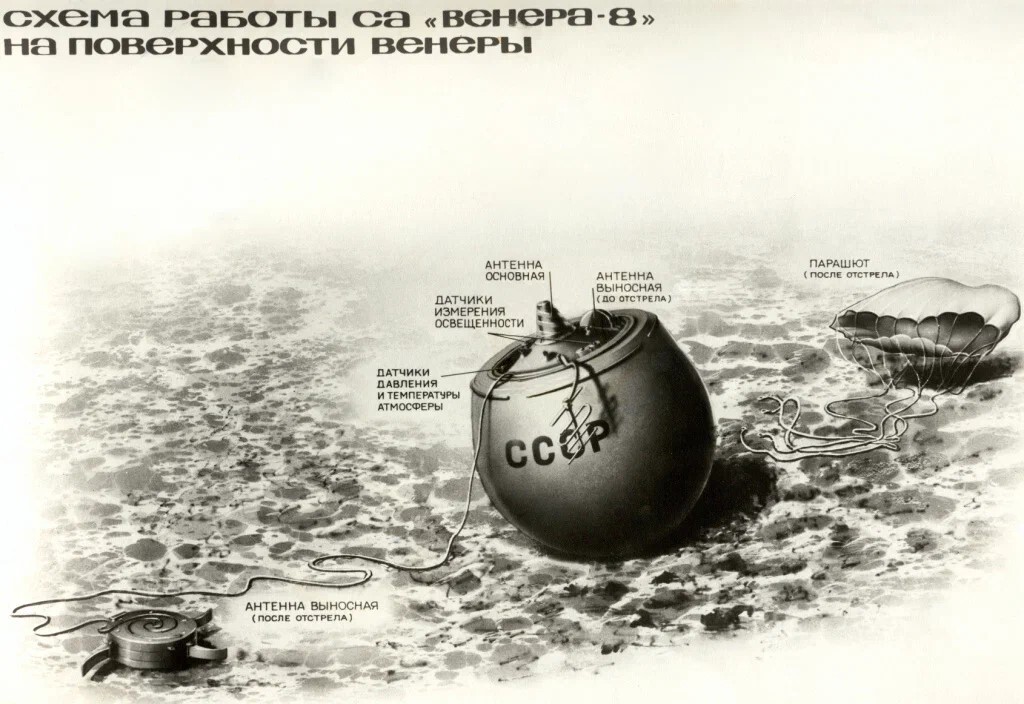

According to the Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences (IKI), a few months later, Kosmos-482 was purposely split into a descent module and a flight module. The flight module "left orbit" (fell to Earth) in 1981, an IKI posting adds.

As for the descent module's nosedive to Earth, Oleg Korablyov, head of the department of planetary physics at IKI, said it should have had sufficient heat protection.

"If it could be found," Korablyov said, "it would be very interesting to study it in order to understand the effects of long-term exposure to cosmic radiation on structural materials."

Will it float?

Russian space historian Pavel Shubin is floating the idea that Kosmos-482's Venus landing hardware might be found bobbing in ocean waters.

Shubin placed the last orbit of the station on a sea traffic map, noting where it entered and where it could have flown.

Shubin's posting reads (in Russian; translation by Google): "The capsule has no aerodynamic quality, so it should land along the route. Maybe someone will find it. The question is in the buoyancy of the station. It turns out to be at the limit, but it still looks like it should float in seawater. If it sinks, there is no chance of finding it. Although it can withstand a kilometer of water" (in the event the object has sunk out of sight).

That said — and apologies to TV's David Letterman — will it float?

Open source

Marco Langbroek is a leading satellite tracker and lecturer in optical space situational awareness at Delft University of Technology in the Netherlands. He and astrodynamicist Dominic Dirkx created an open-source TU Delft Astrodynamics Toolkit (Tudat) that they used to predict when and where the wayward Venus probe would come down.

Langbroek and Dirkx wrote an informative post mortem on the descent craft's interesting reentry and the confusion it left in The Space Review, which you can find here.

"And now it has finally reentered," Langbroek and Dirkx wrote. "The big question on everybody's mind is: Where did it reenter, and when exactly?"

Different estimations

Several organizations followed the doomed probe, such as the U.S. Department of Defense, the European Space Agency (ESA) and The Aerospace Corporation, Langbroek and Dirkx explain. All of these groups posted somewhat different reentry estimates.

Langbroek said it is very likely that the space leftover survived reentry through Earth's atmosphere intact, before impacting at an estimated speed of 65 to 70 meters per second after atmospheric deceleration.

"Maybe, one day, something odd with Cyrilian markings will wash up on an Australian or Indian beach," Langbroek and Dirkx write.

Stacked imagery

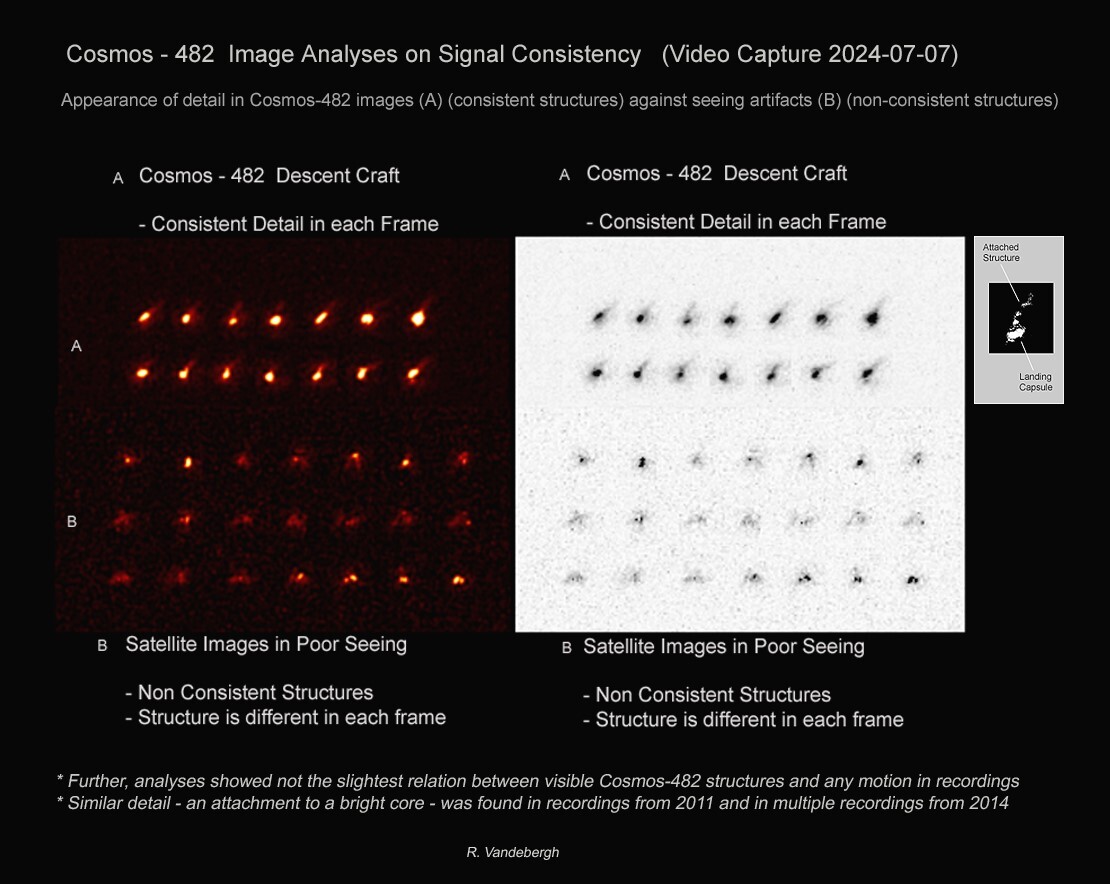

Ralf Vandebergh, also of the Netherlands, is a photographer specialized in imaging small objects orbiting Earth, tracking spacecraft and producing informative images using small to moderate aperture telescopes.

Vandebergh stacked imagery data captured from his first observation of the errant spacecraft in 2011, followed by processing of more recent observations. All results pointed to the existence of an "attached structure" to the Kosmos-482 descent craft. He speculated that, perhaps, the descent vehicle had deployed its parachute. Whatever the case, that appendage is now long gone following reentry.

Vandebergh published his pre-reentry Kosmos-482 photo assessment here.

Unhelpful physics

"In general, reentry predictions have a certain amount of challenge. You're trying to pinpoint something that is coming down that's moving really fast," said Marlon Sorge, executive director of The Aerospace Corporation's Center for Orbital and Reentry Debris Studies (CORDS).

CORDS offers expertise regarding space debris and space traffic management and maintains a reentry database that documents objects and payloads that plow into Earth's atmosphere, such as Kosmos-482.

"Being off even a little bit represents hundreds or thousands of kilometers in distance on the surface of the Earth," Sorge told Space.com. Also at play, he said, are some "unhelpful physics." For example, solar activity affects the density of Earth's atmosphere, which then impacts when and where an object is going to reenter.

Real-time unknowns

Gregory Henning, a CORDS project leader, pointed out other issues that make reentry predictions tricky as well.

"You don't know real-time how that object is behaving," Henning said. "Is it tumbling? Have pieces broken off? Is it in a stable orientation? So you don't really know real-time what kind of surface area the object is presenting to the atmosphere."

The spherical nature of the descent part of Kosmos-482 was a literal "odd ball" in terms of a reentry. Keep in mind that it was built to enter and endure a punishing plunge into the atmosphere of Venus.

The Venus lander was made to withstand the extremely harsh conditions of Venus' hostile atmosphere, ESA experts have said, and was designed to take 300 G's of acceleration and 100 atmospheres of pressure.

"I have not seen anything that would suggest that there were any sightings. But again, being a design to survive a Venus entry, it's fairly likely that it could have survived," Sorge said. "That means you wouldn't see the whole spectacular display of a breakup and a bunch of pieces flaming down that make other reentries so noticeable," he said.

Vexing problem

"All models are wrong, and some are useful," said Darren McKnight, senior technical fellow at LeoLabs, a company that monitors activity in space to reveal threats to safety and security.

The reentry of space objects has been a vexing problem since the beginning of the space age, McKnight told Space.com, because there are at least three physical phenomena that all have large uncertainties.

Those phenomena combine to represent the total uncertainty of where and when an object is finally going to meet its ultimate return to Earth, McKnight said.

Bulges and dips

At the crux of reentry question marks are atmospheric density profiles, the orientation of the space object, along with the way that it melts, vaporizes, and (perhaps) breaks up.

"The density of the atmosphere changes drastically for a given reentry point in space based upon the solar flux/activity, time of day, etc. There are diurnal bulges and dips in the atmosphere that change during the course of the day, which also are affected by solar storms that occur, overlaid on top of the background solar activity," said McKnight.

The transit of these fluctuations also varies as Earth progresses through seasons of the year, he added.

Magic altitude

When a space object reaches a "magic altitude" of 50 miles (80 kilometers) above Earth, substantial heating starts to occur, McKnight said. "The orientation of the space object is critically important to accurately assess how the heating and drag effects will accelerate," he said.

Toss into the mix that certain forces exerted on the space object cause an incoming object to rotate.

"This may even cause there to be a net lifting effect that would delay the reentry of the space object," said McKnight. This is sometimes called skipping, because it's analogous to a thrown stone skipping over the surface of a pond.

McKnight said that he's been working in aerospace engineering, space safety, and space operations since 1986. "Reentry physics and predictions in that domain have advanced the least over that timeframe," he concluded.

Leonard David is an award-winning space journalist who has been reporting on space activities for more than 50 years. Currently writing as Space.com's Space Insider Columnist among his other projects, Leonard has authored numerous books on space exploration, Mars missions and more, with his latest being "Moon Rush: The New Space Race" published in 2019 by National Geographic. He also wrote "Mars: Our Future on the Red Planet" released in 2016 by National Geographic. Leonard has served as a correspondent for SpaceNews, Scientific American and Aerospace America for the AIAA. He has received many awards, including the first Ordway Award for Sustained Excellence in Spaceflight History in 2015 at the AAS Wernher von Braun Memorial Symposium. You can find out Leonard's latest project at his website and on Twitter.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.